In Her Words

Valentina Suntzeff – Autobiography (Cont.)

CHAPTER II

LIFE IN THE UNITED STATES

If you asked me why we decided to go to the United States the answer is – the pursuit of individual freedom which did not exist in Russia either before or after the Revolution. Chinese culture was too alien to our way of life. News from Russia continued to be discouraging. People were afraid to express any direct criticism of government for fear of arrest. The prospect of living under the pall of such fears seemed to us intolerable. Even now, after the passage of fifty years since Communist Revolution, when it is said that life in Russia is much more free and there is no longer such oppression, Dr. Andrei Sakharov, an outstanding physicist, is unable to come to any scientific meetings outside the USSR, and finds cooperation with his colleagues outside Russia very limited and difficult to achieve because of restrictions to freedom of communication.

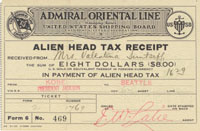

Of course we were still young then and did not conceive of the difficulties ahead. We were early immigrants from Russia before any organized aide to displaced persons existed. We arrived in the United States in 1923 with $12.00 in our possession. We left most of our relatives behind. Our family consisted of my husband, Alexander, my daughter, Ludmilla, age 9, and myself. We were met in San Francisco by my brother-in-law. He had emigrated to the United States the year before and was working as a longshoreman. His Russian fiancee came over with us. In Russia my brother-in-law was a medical student. (Later he finished Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago and became a practicing physician in Quincy, Illinois. He died several years ago from a heart ailment.)

We rented one room. As everyone knows, a room has 4 corners. One corner was the bedroom, two other corners were our kitchen and dining room, and the fourth corner was our sitting room where there was a small sofa on which our daughter slept. I could find no work where I could apply my knowledge of medicine. I was forced, because of my acquired habit of eating, to accept the first job I could find which was in a sewing factory pulling basting threads from coats for 8 hours a day. Two weeks later I was promoted to operating a sewing machine.

Imagine this – I had never used a sewing machine of any kind before. A young man from the office explained to me in broken Russian how to operate this electric monster. But the world is not without kind people. One Italian girl took me under her wing and taught me in one hour how to operate an electric sewing machine.

Late one afternoon my boss ran to me, pulled me by the sleeve and motioned me to follow him. In the rest room on the floor I found one of our women lying unconscious. The boss, an excitable individual, found another worker who was also Russian but knew a little English and could translate my instructions. After treating my patient who became conscious, I started to leave, but the boss wanted to talk to me. After much gesticulation he wanted to find out if I really was a doctor, and, if so, why was I working in his factory for $12.00 a week. My interpreter asked me again and again “Are you a chiropractor?” I had not the slightest idea what the word meant so I innocently answered “Yes.” Unfortunately, my interpreter did not know what a chiropractor was either and told the boss that I probably was one.

We lived on $12.00 a week until a month later my husband found work in a factory, not as a mechanical engineer, but as an unskilled laborer. He was strong and muscular but working conditions were very unsanitary and I was afraid he would ruin his health. I told him that we may never be able to return to our professions and he needed to find a less hazardous job. So we tightened our belts and he accepted an apprenticeship in an upholstery shop on minimal salary. He finished his apprenticeship, soon began to earn substantial wages and life became easier economically. This proved to us that an intelligent person can learn many kinds of skills if he applies himself to this task.

In San Francisco we were a part of a big Russian ethnic group. We now lived in the same household with my husband’s relatives, who joined us from Harbin, China. We only spoke Russian in the home, saw only Russian friends, and joined a Russian club. Life became comfortable as wages improved. There were picnics in the mountains, many Russian parties with singing and dancing. Our daughter was doing well in school but all her friends were other Russian children.

We began to realize that though our lives became more comfortable and enjoyable, there seemed little prospect for our professional careers to which we were both committed. We were becoming impatient and discontented.

One day on a street in San Francisco I accidentally saw my former classmate from women’s medical college. After warm greetings, she asked me what we were doing. I told her that I was a seamstress in a factory. She said, “Have you lost your mind, wasting your abilities this way? What is Alexander doing?” I told her that he was an upholsterer. She thought a minute, spoke of a friend who was organizing a match company near St. Louis. If my husband would be interested, she offered to write her friend. My husband was delighted at a chance to return to engineering. Soon he was on his way, on borrowed money, for a job interview with the understanding that my daughter and I will follow him in a few months if this works out. A couple of days after his arrival in St. Louis I received a telegram that he accepted the job as mechanical engineer and to come on right away. So we packed our small belongings and a week later arrived in Ferguson, Missouri (a suburb of St. Louis). This is where we still live, though our home is now quite different from the small upstairs apartment over a grocery store that we first rented.

I immediately began to apply for an internship in St. Louis hospitals but, because of my broken English and being a woman, nobody would take a chance. I even applied for a nursing position but was turned down because I had no training in this field. I remained a housewife for four years though still continuing my search for opportunity to return to my chosen career. As usual for us, this opportunity came unexpectedly. We were invited to a party in honor of a Bulgarian doctor who was visiting his parents. There I met three Russians, Dr. Boris Sokoloff, a physician, Dr. Ivan Parfentjev, a biochemist, and Dr. William Devrient, a physician. They were working as a research team in Washington University School of Medicine with an outstanding endocrinologist, Dr. Leo Loeb. Dr. Sokoloff asked me if I wanted to join their research team. I enthusiastically agreed. I was unsure of myself after being out of the medical field for about 8 years and wanted to prove myself, so I asked that I work for three months without pay to determine whether I could be productive in research. After three months, I joined the Department of Pathology of Washington University School of Medicine as a research fellow. It was the delight of my life to return to the medical field. Dr. Leo Loeb was then Head of the Department of Pathology. Our team worked together cooperatively and congenially for several years. Our task was cancer research which was then in early stage. We studied the concentration of lactic acid in the blood of normal and cancer-bearing mice.

In 1934 other members of our research team left to accept positions elsewhere. Dr. Leo Loeb offered me a position in the Pathology Department which I gladly accepted. Our team research was in the field of endocrinology. We studied the role of endocrine glands in the development of cancer.

Dr. Loeb was one of few scientists who recognized even then the relationship between endocrine glands and development of mammary gland cancer. Though the reason for this is still an unsolved mystery, the existence of such a relationship has by now been firmly established. Dr. Loeb pioneered in this field and I became his colleague in this endeavor. We had hundreds of animals under experiment. We were proceeding with our experiments deliberately and methodically, slowly increasing the dosage and obtaining significant results indicating relationship between endocrine glands and development of mammary gland cancer. I did suggest to Dr. Loeb that the dosage be massively increased. He was reluctant, fearing this would kill too many experimental animals prematurely while I urged this would demonstrate the validity of hypothesis more quickly. He replied, “Why be in such a hurry?” In the meantime, Dr. Lacassagne of the Pasteur Institute, Paris, France, published an experiment in which 5 mice he injected with massive doses of female hormones all developed cancer of the mammary glands. He was given credit for this discovery. Soon afterward Dr. Lacassagne visited Dr. Loeb at Washington University. I still remember how bitter I felt about all this recognition going to Dr. Lacassagne. Dr. Loeb, however, was philosophical about this.

St. Louis is hot in the summertime. This was before the days of air-conditioning. Our experimental animals became lethargic from heat. Fearing their loss from heat prostration, I brought some essential animals to our home basement. There we continued the experiments, with my daughter, now a college student, helping me with injections.

I was generally quick in understanding the principles of physics, mathematics or biological sciences. However, learning a language has always been a laborious chore. There was one colleague, Dr. Edward Burns, who helped me a great deal with acquiring facility with the English language. It took him a month to teach me to pronounce the word “theelin” correctly, but I finally mastered this and other intricacies of the English language. However, this has remained for me a sensitive area where I am lacking in confidence and feel unsure.

In this period of my life, while working with Dr. Loeb, I acquired knowledge and skill in the field of research and became confident that I could contribute to the developing field of cancer research.

The biggest surprise and disappointment of my professional life has been the realization of the submerged place of women in the field of medicine. I was accustomed to being completely accepted in Russia as a competent physician with no discrimination because of my sex. It was a real shock to learn that admission to any medical school is much more difficult for a woman and the number of internships limited. Establishing independent practice was very difficult in the 1930s. People did not trust the competence of women doctors, preferring men instead. Another surprise was the women’s attitude. They seemed afraid to compete with men physicians. If they married another physician the women would usually play a secondary role professionally. This discrimination against women doctors is slowly diminishing but still exists. In the field of scientific research there are to this day comparatively few women who are active and successful.

In St. Louis we met some Russians but also became close friends with American families. Learning to play bridge helped socially. We soon began to feel a part of this community despite our limited English and relaxed after our stormy transplantation from one country to another. We began to feel that we are Americans. We continued to be a close-knit family, seldom apart. We kept in touch with our relatives and visited back and forth frequently despite long distances. Another brother of my husband escaped from Russia and joined us in the United States in early 1930s.

I have always liked active sports. When I was a young woman in Russia I went skiing and ice-skating in the winter with groups of young people, swam in rivers and lakes, loved the game of tennis and horseback riding, especially on my uncle’s estate where we visited in the summer. Swimming is the chief sport that I have continued to this day, in rivers, lakes and the ocean – sometimes in a swimming pool if nothing else is available. Many of our vacations have been in places where swimming was possible. We have never lived in cold enough climate in the United States where we could continue with winter sports.

In late 1930s there were changes in my personal life. My daughter received her master’s degree in Social Work from Washington University. She went to work for Family Service in Memphis. There she met and married her husband, Thomas D. Gafford, who is a civil engineer. Several years later I became a grandmother. We have continued to see my daughter and her family often and retain close family ties.

I taught Histology for three years during World War II. I found this interesting at first but later somewhat monotonous. I decided this was not really a good field for me and asked to be relieved of this assignment.

After Dr. Loeb retired in 1941 I had two offers – one from Dr. Edmund V. Cowdry, head of the Department of Anatomy, and Dr. Evarts Graham, head of the Department of Surgery. Both were equally interesting offers and I had a hard time deciding between them. I asked the opinion of one of my colleagues in the medical school who knew both men. He replied that their research was completely different. Dr. Cowdry’s method is the development of research teams while in Dr. Graham’s department each researcher works independently. I have always liked working with a team rather than alone so I decided to join the staff of Dr. Cowdry. I have remained happy with my decision. We had freedom to work and he has always been a source of inspiration. Our group was very congenial. Dr. Christopher Carruthers was the biochemist in our team. These were the most productive and satisfying years of my professional life.

Our major research was on cancer of the skin. An initial problem was how to develop a technique for separating epidermis from dermis; this proved fundamental to the treatment of cancer of the skin. I got the idea how this could be done when I was peeling back the skin of a tongue in my kitchen. This research was published in 1942. A methodical, patient approach with careful attention to detail is necessary for any productive biochemical research. Learning this was a difficult task requiring hard work and effort since I am by nature a person of quick decisions. Another difficult aspect to cancer research is learning that at times your findings are essentially negative – that your contribution to scientific knowledge may be that a particular approach is not a productive one. My belief is that a team approach is highly effective in biological research. Biochemical problems are generally too complex and the fields of histology, pathology and chemistry are too inter-related for any one discipline alone to find solutions. Scientists from several fields need to be a part of a working team with each contributing to the development of a research project. I have continued active in cancer research until I reached the age of eighty. I am Research Associate Professor Emeritus. Since then my research activities have diminished. I am now winding up my latest research projects. I am facing a very hard decision – should I stop my research completely since my vision has become impaired after my cataract operation?

Since late 1940 there have been several teams of Russian scientists working in cancer research which have visited Washington University School of Medicine. This offered an interesting opportunity for me to learn first-hand more about the progress of cancer research in Russia. My husband and I usually had them in our home for dinner and learned more personal details about life of scientists in Russia. Economically life there was a comfortable one, but they avoided discussing any subject of a political nature. We met some scientists from our part of the country in Russia. One scientist was from Perm, where we lived after we were married. He told us that our summer home in the country was now a children’s day nursery. The nearby woods and surrounding countryside were now industrialized. There was a hydroelectro plant, a munitions factory and other heavy industries. Drilling for oil has been going on for several years, ever since oil was discovered near where we used to live. My husband recalls that many years ago when they drank water out of a small local stream it smelled faintly of kerosene. The city of Perm is now around a million – it was 80,000 when we lived there.

I think I have reached a time in my life when I am becoming more domestic. This October my husband and I will be married 60 years. I am happily married and very lucky to have our daughter, Ludmilla, who has always been a source of pleasure to us both. My granddaughter, Valentina, is an architect, temporarily staying home with her young child but planning to return to her professional career. My grandson, Alexander, is a recently graduated mechanical engineer, doing very well and highly interested in his profession. I am still in touch with my husband’s many relatives, though my own relatives who remained in Russia stopped corresponding long ago. My husband continues to work full time as a mechanical engineer. My personal life has many rich satisfactions. My main regret is that I will not see what my great-grandson will be like when he becomes an adult!

We are still searching for answers into causes and treatment of cancer. Scientific research in this field is closely interwoven and the final answers, when these come, will be based on the years of research which had already been done as well as on what is discovered today.

In the United States, which is now OUR country, we found the intellectual freedom for which my husband and I were searching – so our dream and hopes became a living reality.

<< Previous | 1 | 2

Related Links:

Return to Oral Histories

Return to In Her Words

Back to Top