In Her Words

Valentina Suntzeff – Autobiography

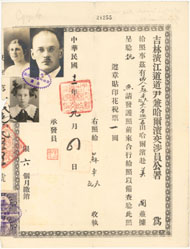

Valentina Suntzeff was born in Kazan, Russia in 1891. After the Russian Revolution, her family emigrated, first to China and then the United States, initially settling in San Francisco. In this autobiography, written in 1973, Suntzeff recalls her medical education and career as a woman in Russia and compares it with what she encountered in America. Though it took several years for Suntzeff and her husband to find work in their chosen fields, they eventually found success in their professional careers in the U.S.

Suntzeff wrote the autobiography at the request of author Cecyle S. Neidle, who was preparing a book on the experiences of foreign-born women and the roles they played in the U.S. Valentina Suntzeff and Gerty Cori were two of the women who were to be featured in the chapter on foreign-born women in medicine. The book, America’s Immigrant Women, with several pages about both Suntzeff and Cori, was published in 1975.

[The following autobiography has been edited for spelling only.]

CHAPTER I

LIFE IN RUSSIA

Valentina Suntzeff, M.D.

I was born the 28th of February, 1891, in Kazan, Russia. My family consisted of my parents, two brothers, two sisters and me – I was the third oldest child. My father was a doctor. I was very close to my father and admired him. I would sneak into his study and look at his medical books and journals. I was fascinated by pictures of the anatomy of man. When I was 8 years old I decided to follow in my father’s footsteps.

Part of our house was used by my father as his office and waiting room, and where he did minor surgery. One day my curiosity got the best of me and I hid behind the door and watched him perform some minor surgery. He discovered me there while he was in the middle of surgery, pulled me out, and told me if I wanted to watch to do so openly and not behind doors. We had a talk afterwards and I told him of wanting to go into medicine. He encouraged me, believing I was capable of this. I was then 9 years old. Unfortunately my father died when I was in my early teens. My mother was usually agreeable to my father’s ideas, and completely supported my ambition. My older brother and sister thought that it would be a fine thing if I went into medicine. However, when I consulted my father’s close friend who was a doctor, he strongly discouraged me; he said it was too hard for a woman; and also there was very little opportunity to pursue the career of a doctor. But I held fast to my decision. My maternal uncle, a lawyer, encouraged me and partially financed my way through medical school. I had a wonderful teacher of biology in the last two years of gymnasium, who further strengthened my interest in the field.

I received all of my education in Russia. I finished gymnasium in Kazan, which is quite a large city on the Volga River. Our gymnasium could be compared with your high schools; the only difference is that our program there was broader than that of your schools. After we finished our gymnasium (high school) we could enter most of our universities without any examination. At the gymnasium we were all required to take certain basic subjects, such as Russian literature, physics and mathematics regardless of what we were going to major in later. Our courses were so thorough that most American universities would give us two years of college credit, so that instead of entering as freshmen we could enter as juniors. So far as I know, all of our medical schools and universities were supported by the Government. I say medical schools and universities, because we women had separate medical schools which were not affiliated with the universities as were the medical schools for men. This explains why the tuition in our universities was very low, especially in comparison with the tuition which students have to pay here. For example, I paid 50 rubles a year in my medical school which covered laboratory fees and all expenses except books. Fifty rubles at that time was equivalent to about 50 dollars.

Our students in general had much less money than the students here. Many students were supporting themselves completely or partially by tutoring students of the gymnasium or grammar schools as I did. There was a student mutual aide, the aim of which was to help our poor students financially. This organization conducted a dining room for students, which served meals at very low cost. For example, for 12-15 kopecks (about 12-15 cents) you could get soup, a piece of meat with potatoes and one vegetable, and as much bread as you wanted. Quite often when students had no money they came to the dining room and had soup and plenty of bread for 5 kopecks. In this way money could be stretched for several days until they received their allowance.

It was absolutely not fashionable to be dressed up in the university. Our dresses were always very tailored, and nobody used make-up, but they all tried to be neat. In my time the type of women students whom we called “blue stockings” had already disappeared. I think this term “blue stockings” is used here to indicate a type of woman who did not care about her appearance and who liked to look as mannish as possible.

When I went to school we did not have co-educational schools. When I was ready for medical school I could not enter the medical school for men which was a part of the university because it was prohibited, so I entered a women’s medical school. However, several years later we women were finally permitted to attend medical schools with men. In my time we had four medical schools for women and ten for men.

Our first higher medical courses for women were organized in St. Petersburg in 1872. Borodin, a well known Russian composer, who composed the beautiful opera Prince Igor, was one of the pioneers who fought for the emancipation of higher education for women. He was a chemist also and his main work was research in plant physiology. He was one of the founders of the school of medicine for women where he taught for many years. He was buried at Nevsky Monastery where there is now a monument. A silver crown was placed on his coffin with an inscription “To the Founder, Protector and Defender of the School of Medicine, From the Women Graduates Between 1872-87.”

Two years later, in 1874, the first independent medical college for women was established in London in the house of Dr. Anstil. However, there are a few cases of women receiving higher medical education before that date. Miss Elizabeth Blackwell, in 1844, applied for admission in all 13 medical schools in the United States. Twelve of them refused her petition. One, Geneva Medical College in New York, accepted her. Most of their objections were that “it was improper and immoral to initiate a woman into the nature and laws of her own organism.” I think we had the same prejudices against higher medical education as you had here, but somehow we developed our education in this particular line much more successfully than you did. Eighteen years after the first medical school for women was established in Russia we had 12,521 doctors, of whom 409 were women. In my time, after we were graduated from medical school, we had no difficulty in receiving a position. Our applications were considered on the same basis as those of men. We were not discriminated against because of our sex. One’s experience and ability were the factors considered when applying for a position. A large number were employed by the Zemstvo.

I entered medical school in 1911. Medical school was hard and involved a lot of intensive study and long hours. At the same time I became very active in medical student mutual aide organization. We raised funds for needy students by giving balls and concerts. I met the famous Fyodor Chaliapin when I sought to secure him for one of our concerts. He bluntly refused, saying, “If I give you my time, I would have to give to all charities.” I can still remember how disappointed and hurt I was by his refusal. I spent so much time doing this charity work that I got behind in my studies. Our professor of anatomy was very strict. I had to catch up in my study of anatomy. I decided to go to the anatomy amphitheater much earlier than my class. I was alone in the corner, and the only lights were those over the corpse on which I was working. I raised my head and saw the hand of another nearby body drop. I was so startled and terrified that I ran hurriedly out. Another medical student met me in the hall and asked “What happened, Valentina? You are as white as a ghost.” I told her about the incident. We returned and replaced the dropped hand.

There was still time for fun as well as work. We went to concerts and ballets, sometimes going hungry in order to buy the tickets. There were group singings and small parties, at one of which I met my husband. Our relationship with men was informal and casual. We had no dates but gathered together instead and had a good time.

Early in my second year of medical school I became engaged. We were married late that fall, returning to school after a large family wedding. I continued my medical education and my husband continued his study of mechanical engineering. Contraceptives were still in their infancy and I became immediately pregnant but finished my second year. I stayed home a year after my baby was born. My relatives predicted that I would never return to medicine – they even made bets. One relative bet a famous painting that he owned. But I did return for my junior and senior years and finished my medical education. The school was about 1,000 miles away from my new home; the journey took two days by train. My mother-in-law looked after my baby while I was gone. My husband, who had graduated from engineering school, was also living with his parents. Each time I returned home I was filled with anxiety. Will my child not know me and turn away? But each time when she saw me she would come running to hug me. I am certain that I would not have been able to finish medical school without help and backing from my husband. My in-laws, who were well-to-do people, tried to persuade me that I did not need to earn any money and that I was needed at home with my child. But my desire to return to my profession remained strong and my husband encouraged me. He told me I should finish medical school since I may regret not doing so later and this would always stand between us.

After graduation from medical school in 1917 I had many choices for a position as a doctor in the city where my husband lived. My first work was as a doctor for a big ammunition plant working in a hospital where there were eight doctors in addition to myself. Out of the nine doctors, four were women. It was a large factory in which almost all workers were men. This fact did not matter, since men came to women doctors just as freely as they would have come to men doctors.

I have no statistics to show how many women doctors we had in Russia before the Revolution, but I know there was a very large number. We women doctors worked equally with men doctors. I was very much surprised to learn that there was a medical association for women doctors in the United States. In Russia no such organization would have existed. You could find women doctors who specialized in any field of medicine. I have known quite a number of women surgeons. However, I must admit that our best and most well known surgeons were men. I think this fact can be readily explained. We women are newcomers in the medical profession, and I may say, in many professions. It has not been so long since women’s activities were limited to the home.

World War I was already in progress. I was in charge of internal medicine wards. Then I changed to Zemstvo organization and became the head of an isolation hospital for infectious diseases, in spite of my colleagues warning me that I would bring these infectious diseases home – which I never did. I received nothing but bare walls, and instructions to organize a hospital for infectious diseases. It was a difficult and challenging task, very rewarding when it was finally accomplished.

The isolation hospital was located away from town. The head nurse had no one to whom she could turn after hours if there was an emergency. The only telephone in town was at the ammunition plant. Wearing my most becoming dress, I went to the plant manager and told him of my dilemma. He asked me when would I need the telephone. I said immediately, hoping for one in a month. The telephone was installed in two days.

The question of state medicine is very interesting and quite new for American people, but not for Russians. It is a mistake to think that state medicine was established in Russia only after the Revolution. Our Zemstvo-medicine was really an early form of state medicine. In 1864 Alexander the Second organized the Zemstvo and from then on this organization became an established one. It became a very interesting and powerful organization. Before this reform our country had no organized medical help. You will probably want to know what Zemstvo was. The Zemstvo was an elected body invested with certain limited powers. The basis of representation was:

Nobility 43%

Peasantry 38%

Others 19%

All members of the Zemstvo were elected on a three-year basis. The activity of the Zemstvo consisted of the following:

1. The determination and collection of district and provincial taxes.

2. The establishment of offices for this purpose.

3. The management of the properties of the Zemstvo.

4. Relief work during disasters.

5. The construction of roads, canals and other means of communication.

6. The arrangement of mutual insurance.

7. The construction and management of hospitals, charity organizations, asylums, relief of the poor and sick.

8. Advancement of public health, veterinary supervision and treatment.

9. Fire prevention.

10. Advancement of popular education, building and management of schools and libraries.

11. Eradication of harmful insects and plant diseases.

You can see that the activities of Zemstvo were very wide. The Zemstvo and similar city organizations did their work very successfully, especially in the case of popular education and medical care for the public. In Russia Zemstvo medical care and Zemstvo schools were of a very high standard. They were both absolutely free to the people. Most of our Zemstvo workers were very idealistic and liberal. Corruption was practically was unknown among Zemstvo employees and they were satisfied with a modest position and salary. I must admit that we did not have enough physicians in Russia and our Zemstvo and those employed by Zemstvo were overburdened. Every Zemstvo doctor was in charge of a small hospital and usually he had a pheldsher and one midwife to help him (pheldsher – one with a higher education than a nurse and less education than a doctor). Each hospital supervised a certain district. Every person from this district was free to come to the hospital for medical help. If he needed medication he received it; if it was necessary he was admitted to the hospital. No fees were charged but each person paid a certain small tab annually. Consequently they did not neglect to call the doctor because of lack of money. But I again want to emphasize that our Zemstvo-medicine was far from perfect because we did not have enough doctors and little money, but some of our best doctors came from Zemstvo-medicine. From my own experience, in addition to my work in the ward where I had about fifty patients, I was in the dispensary every day where I had to examine fifty or more patients with a little help from the pheldsher. Besides I always had several calls daily.

Civil war began in Russia, culminating in the overthrow of the monarchy – 1917-1918. The town of Perm was caught up in the civil war. It was occupied by the Bolsheviks and was reoccupied by the White Army, an anti-Bolshevik group from Siberia. A decision was made to evacuate the ammunition plant. My husband was then in the White Army in charge of an evacuation train. I became the doctor in charge of the train. We moved slowly through Siberia, through Barnul, Tomsk, and Irkutsk, taking about two months. We were in crowded freight cars, taking turns to keep the fire going to keep warm. Sometimes the bridges ahead of us were blown up by the partisans. We had to wait until these bridges were repaired by army engineers so that we could go ahead. The Siberian railroad had two tracks. One was occupied by Czech, Japanese and other foreign troops participating in fighting the Communists. The other tract was only for evacuation, not for fighting troops, by agreement between Admiral Kolchak, current head of Russian anti-Communist movement, and General Janen, head of evacuation of foreign troops fighting the Communists.

Most of my work as physician for the evacuation train was preventive medicine. Each time the train stopped, I would order everyone to a public bath house. We had very little sickness, no epidemics and no deaths. We arrived safe and sound in Chita. I was mobilized into the White Army in Chita and served as a medical officer. One day my superior officer ordered me to the front. I refused because I needed to be with my small daughter. He threatened to arrest me but I quoted the law which said that I could only be mobilized to a place where I could be with my child. I stayed in Chita as a medical officer. One day, while I was on duty and in charge, 200 wounded soldiers were brought in, many with typhus and typhoid. We had no extra beds in the hospital, so we spread hay on the floor and covered it with clean sheets. We stripped all the soldiers naked to reduce infection. There were no clean clothes available. When we were through I saw a dirty foot sticking out from under a pile of dirty linen. I saw it was an unconscious wounded officer, covered with dirt and lice. I told the orderly to move him. At first he refused, fearing the officer was infectious. I told the orderly that I would arrest him if he refused. Then together we moved this officer, who later recovered and lived. On my return home that day I found two lice on me. I told my husband that I was infected. I developed typhus two weeks later and was very ill. The entire staff who received the contingent of 200 men became infected. We were hospitalized together; one staff member died. The trouble was that during my illness my remaining staff still came to me for instructions and I got little rest. One day my headache was severe and I felt terrible. I told one nurse, abruptly and rudely, to get out, that I was sick and was as much a patient as anyone else. After recovery I returned to duty as a medical officer. When I came home to convalesce I was very thin and very hungry. I was alone, found some smoked fish and ate it all. This was the family ration for the week. You can imagine how I felt afterward.

Life in Chita was very hard. The climate was severe, the food supply limited, and housing crowded. Our household consisted of our three families totaling 12 people. We lived together in four rooms almost without furniture.

As the resistance to Communism collapsed, we were evacuated from Chita to Harbin, China. We lived there for two years. I did some work in a railroad hospital and some private practice. But there was very little opportunity for Russian professionals in China. My husband only found work as a master mechanic in the railroad shop. We decided to move to the United States, and did so in 1923.

CHAPTER II

LIFE IN THE UNITED STATES

If you asked me why we decided to go to the United States the answer is – the pursuit of individual freedom which did not exist in Russia either before or after the Revolution. Chinese culture was too alien to our way of life. News from Russia continued to be discouraging. People were afraid to express any direct criticism of government for fear of arrest. The prospect of living under the pall of such fears seemed to us intolerable. Even now, after the passage of fifty years since Communist Revolution, when it is said that life in Russia is much more free and there is no longer such oppression, Dr. Andrei Sakharov, an outstanding physicist, is unable to come to any scientific meetings outside the USSR, and finds cooperation with his colleagues outside Russia very limited and difficult to achieve because of restrictions to freedom of communication.

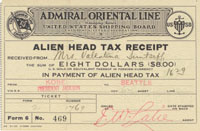

Of course we were still young then and did not conceive of the difficulties ahead. We were early immigrants from Russia before any organized aide to displaced persons existed. We arrived in the United States in 1923 with $12.00 in our possession. We left most of our relatives behind. Our family consisted of my husband, Alexander, my daughter, Ludmilla, age 9, and myself. We were met in San Francisco by my brother-in-law. He had emigrated to the United States the year before and was working as a longshoreman. His Russian fiancee came over with us. In Russia my brother-in-law was a medical student. (Later he finished Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago and became a practicing physician in Quincy, Illinois. He died several years ago from a heart ailment.)

We rented one room. As everyone knows, a room has 4 corners. One corner was the bedroom, two other corners were our kitchen and dining room, and the fourth corner was our sitting room where there was a small sofa on which our daughter slept. I could find no work where I could apply my knowledge of medicine. I was forced, because of my acquired habit of eating, to accept the first job I could find which was in a sewing factory pulling basting threads from coats for 8 hours a day. Two weeks later I was promoted to operating a sewing machine.

Imagine this – I had never used a sewing machine of any kind before. A young man from the office explained to me in broken Russian how to operate this electric monster. But the world is not without kind people. One Italian girl took me under her wing and taught me in one hour how to operate an electric sewing machine.

Late one afternoon my boss ran to me, pulled me by the sleeve and motioned me to follow him. In the rest room on the floor I found one of our women lying unconscious. The boss, an excitable individual, found another worker who was also Russian but knew a little English and could translate my instructions. After treating my patient who became conscious, I started to leave, but the boss wanted to talk to me. After much gesticulation he wanted to find out if I really was a doctor, and, if so, why was I working in his factory for $12.00 a week. My interpreter asked me again and again “Are you a chiropractor?” I had not the slightest idea what the word meant so I innocently answered “Yes.” Unfortunately, my interpreter did not know what a chiropractor was either and told the boss that I probably was one.

We lived on $12.00 a week until a month later my husband found work in a factory, not as a mechanical engineer, but as an unskilled laborer. He was strong and muscular but working conditions were very unsanitary and I was afraid he would ruin his health. I told him that we may never be able to return to our professions and he needed to find a less hazardous job. So we tightened our belts and he accepted an apprenticeship in an upholstery shop on minimal salary. He finished his apprenticeship, soon began to earn substantial wages and life became easier economically. This proved to us that an intelligent person can learn many kinds of skills if he applies himself to this task.

In San Francisco we were a part of a big Russian ethnic group. We now lived in the same household with my husband’s relatives, who joined us from Harbin, China. We only spoke Russian in the home, saw only Russian friends, and joined a Russian club. Life became comfortable as wages improved. There were picnics in the mountains, many Russian parties with singing and dancing. Our daughter was doing well in school but all her friends were other Russian children.

We began to realize that though our lives became more comfortable and enjoyable, there seemed little prospect for our professional careers to which we were both committed. We were becoming impatient and discontented.

One day on a street in San Francisco I accidentally saw my former classmate from women’s medical college. After warm greetings, she asked me what we were doing. I told her that I was a seamstress in a factory. She said, “Have you lost your mind, wasting your abilities this way? What is Alexander doing?” I told her that he was an upholsterer. She thought a minute, spoke of a friend who was organizing a match company near St. Louis. If my husband would be interested, she offered to write her friend. My husband was delighted at a chance to return to engineering. Soon he was on his way, on borrowed money, for a job interview with the understanding that my daughter and I will follow him in a few months if this works out. A couple of days after his arrival in St. Louis I received a telegram that he accepted the job as mechanical engineer and to come on right away. So we packed our small belongings and a week later arrived in Ferguson, Missouri (a suburb of St. Louis). This is where we still live, though our home is now quite different from the small upstairs apartment over a grocery store that we first rented.

I immediately began to apply for an internship in St. Louis hospitals but, because of my broken English and being a woman, nobody would take a chance. I even applied for a nursing position but was turned down because I had no training in this field. I remained a housewife for four years though still continuing my search for opportunity to return to my chosen career. As usual for us, this opportunity came unexpectedly. We were invited to a party in honor of a Bulgarian doctor who was visiting his parents. There I met three Russians, Dr. Boris Sokoloff, a physician, Dr. Ivan Parfentjev, a biochemist, and Dr. William Devrient, a physician. They were working as a research team in Washington University School of Medicine with an outstanding endocrinologist, Dr. Leo Loeb. Dr. Sokoloff asked me if I wanted to join their research team. I enthusiastically agreed. I was unsure of myself after being out of the medical field for about 8 years and wanted to prove myself, so I asked that I work for three months without pay to determine whether I could be productive in research. After three months, I joined the Department of Pathology of Washington University School of Medicine as a research fellow. It was the delight of my life to return to the medical field. Dr. Leo Loeb was then Head of the Department of Pathology. Our team worked together cooperatively and congenially for several years. Our task was cancer research which was then in early stage. We studied the concentration of lactic acid in the blood of normal and cancer-bearing mice.

In 1934 other members of our research team left to accept positions elsewhere. Dr. Leo Loeb offered me a position in the Pathology Department which I gladly accepted. Our team research was in the field of endocrinology. We studied the role of endocrine glands in the development of cancer.

Dr. Loeb was one of few scientists who recognized even then the relationship between endocrine glands and development of mammary gland cancer. Though the reason for this is still an unsolved mystery, the existence of such a relationship has by now been firmly established. Dr. Loeb pioneered in this field and I became his colleague in this endeavor. We had hundreds of animals under experiment. We were proceeding with our experiments deliberately and methodically, slowly increasing the dosage and obtaining significant results indicating relationship between endocrine glands and development of mammary gland cancer. I did suggest to Dr. Loeb that the dosage be massively increased. He was reluctant, fearing this would kill too many experimental animals prematurely while I urged this would demonstrate the validity of hypothesis more quickly. He replied, “Why be in such a hurry?” In the meantime, Dr. Lacassagne of the Pasteur Institute, Paris, France, published an experiment in which 5 mice he injected with massive doses of female hormones all developed cancer of the mammary glands. He was given credit for this discovery. Soon afterward Dr. Lacassagne visited Dr. Loeb at Washington University. I still remember how bitter I felt about all this recognition going to Dr. Lacassagne. Dr. Loeb, however, was philosophical about this.

St. Louis is hot in the summertime. This was before the days of air-conditioning. Our experimental animals became lethargic from heat. Fearing their loss from heat prostration, I brought some essential animals to our home basement. There we continued the experiments, with my daughter, now a college student, helping me with injections.

I was generally quick in understanding the principles of physics, mathematics or biological sciences. However, learning a language has always been a laborious chore. There was one colleague, Dr. Edward Burns, who helped me a great deal with acquiring facility with the English language. It took him a month to teach me to pronounce the word “theelin” correctly, but I finally mastered this and other intricacies of the English language. However, this has remained for me a sensitive area where I am lacking in confidence and feel unsure.

In this period of my life, while working with Dr. Loeb, I acquired knowledge and skill in the field of research and became confident that I could contribute to the developing field of cancer research.

The biggest surprise and disappointment of my professional life has been the realization of the submerged place of women in the field of medicine. I was accustomed to being completely accepted in Russia as a competent physician with no discrimination because of my sex. It was a real shock to learn that admission to any medical school is much more difficult for a woman and the number of internships limited. Establishing independent practice was very difficult in the 1930s. People did not trust the competence of women doctors, preferring men instead. Another surprise was the women’s attitude. They seemed afraid to compete with men physicians. If they married another physician the women would usually play a secondary role professionally. This discrimination against women doctors is slowly diminishing but still exists. In the field of scientific research there are to this day comparatively few women who are active and successful.

In St. Louis we met some Russians but also became close friends with American families. Learning to play bridge helped socially. We soon began to feel a part of this community despite our limited English and relaxed after our stormy transplantation from one country to another. We began to feel that we are Americans. We continued to be a close-knit family, seldom apart. We kept in touch with our relatives and visited back and forth frequently despite long distances. Another brother of my husband escaped from Russia and joined us in the United States in early 1930s.

I have always liked active sports. When I was a young woman in Russia I went skiing and ice-skating in the winter with groups of young people, swam in rivers and lakes, loved the game of tennis and horseback riding, especially on my uncle’s estate where we visited in the summer. Swimming is the chief sport that I have continued to this day, in rivers, lakes and the ocean – sometimes in a swimming pool if nothing else is available. Many of our vacations have been in places where swimming was possible. We have never lived in cold enough climate in the United States where we could continue with winter sports.

In late 1930s there were changes in my personal life. My daughter received her master’s degree in Social Work from Washington University. She went to work for Family Service in Memphis. There she met and married her husband, Thomas D. Gafford, who is a civil engineer. Several years later I became a grandmother. We have continued to see my daughter and her family often and retain close family ties.

I taught Histology for three years during World War II. I found this interesting at first but later somewhat monotonous. I decided this was not really a good field for me and asked to be relieved of this assignment.

After Dr. Loeb retired in 1941 I had two offers – one from Dr. Edmund V. Cowdry, head of the Department of Anatomy, and Dr. Evarts Graham, head of the Department of Surgery. Both were equally interesting offers and I had a hard time deciding between them. I asked the opinion of one of my colleagues in the medical school who knew both men. He replied that their research was completely different. Dr. Cowdry’s method is the development of research teams while in Dr. Graham’s department each researcher works independently. I have always liked working with a team rather than alone so I decided to join the staff of Dr. Cowdry. I have remained happy with my decision. We had freedom to work and he has always been a source of inspiration. Our group was very congenial. Dr. Christopher Carruthers was the biochemist in our team. These were the most productive and satisfying years of my professional life.

Our major research was on cancer of the skin. An initial problem was how to develop a technique for separating epidermis from dermis; this proved fundamental to the treatment of cancer of the skin. I got the idea how this could be done when I was peeling back the skin of a tongue in my kitchen. This research was published in 1942. A methodical, patient approach with careful attention to detail is necessary for any productive biochemical research. Learning this was a difficult task requiring hard work and effort since I am by nature a person of quick decisions. Another difficult aspect to cancer research is learning that at times your findings are essentially negative – that your contribution to scientific knowledge may be that a particular approach is not a productive one. My belief is that a team approach is highly effective in biological research. Biochemical problems are generally too complex and the fields of histology, pathology and chemistry are too inter-related for any one discipline alone to find solutions. Scientists from several fields need to be a part of a working team with each contributing to the development of a research project. I have continued active in cancer research until I reached the age of eighty. I am Research Associate Professor Emeritus. Since then my research activities have diminished. I am now winding up my latest research projects. I am facing a very hard decision – should I stop my research completely since my vision has become impaired after my cataract operation?

Since late 1940 there have been several teams of Russian scientists working in cancer research which have visited Washington University School of Medicine. This offered an interesting opportunity for me to learn first-hand more about the progress of cancer research in Russia. My husband and I usually had them in our home for dinner and learned more personal details about life of scientists in Russia. Economically life there was a comfortable one, but they avoided discussing any subject of a political nature. We met some scientists from our part of the country in Russia. One scientist was from Perm, where we lived after we were married. He told us that our summer home in the country was now a children’s day nursery. The nearby woods and surrounding countryside were now industrialized. There was a hydroelectro plant, a munitions factory and other heavy industries. Drilling for oil has been going on for several years, ever since oil was discovered near where we used to live. My husband recalls that many years ago when they drank water out of a small local stream it smelled faintly of kerosene. The city of Perm is now around a million – it was 80,000 when we lived there.

I think I have reached a time in my life when I am becoming more domestic. This October my husband and I will be married 60 years. I am happily married and very lucky to have our daughter, Ludmilla, who has always been a source of pleasure to us both. My granddaughter, Valentina, is an architect, temporarily staying home with her young child but planning to return to her professional career. My grandson, Alexander, is a recently graduated mechanical engineer, doing very well and highly interested in his profession. I am still in touch with my husband’s many relatives, though my own relatives who remained in Russia stopped corresponding long ago. My husband continues to work full time as a mechanical engineer. My personal life has many rich satisfactions. My main regret is that I will not see what my great-grandson will be like when he becomes an adult!

We are still searching for answers into causes and treatment of cancer. Scientific research in this field is closely interwoven and the final answers, when these come, will be based on the years of research which had already been done as well as on what is discovered today.

In the United States, which is now OUR country, we found the intellectual freedom for which my husband and I were searching – so our dream and hopes became a living reality.

Related Links:

Return to Oral Histories

Return to In Her Words

Back to Top