The Modern Era, 1930-1991

|

| The Cancer Research Building under construction in 1950 |

| The first major addition to the Medical School since 1915, architect Harris Armstrong designed this building to link the North and South Buildings. Completed in 1950, it was also the first of the school’s structures to benefit from federal funding. The western facade is now covered by the Becker Medical Library and forms the east wall of the atrium. |

During the last sixty years, the Washington University School of Medicine has moved from regional to national and international fame. Generations of physicians and scientists who trained or worked here have made important contributions to basic knowledge and clinical progress. In 1944, the first Nobel prize came to medical school faculty members for discoveries made here: Joseph Erlanger and Herbert Gasser for research on the properties of nerve impulses. Three years later, in 1947, Carl and Gerty Cori won a Nobel Prize for their research on glucose metabolism. Arthur Kornberg, a former fellow in their laboratory and later Professor and Head of Microbiology from 1950 to 1959, received the Nobel Prize in 1960. Thirteen other Nobel laureates have taught, investigated or trained here, three of them alumni: Earl Sutherland, Class of 1942; Edwin Krebs, Class or 1943; and Daniel Nathans, Class of 1954.

Faculty members have made important contributions to a broad range of scientific and clinical fields – from neuroscience and genetics to radiology, pediatrics, and psychiatry. The school’s long tradition of fruitful interactions between faculty members in basic science and clinical departments bodes well for the future. The modern explosion of biomedical knowledge makes great demands on students and faculty who must work constantly to keep pace with scientific progress. Contact with active investigators helps students understand innovations in research and clinical care.

|

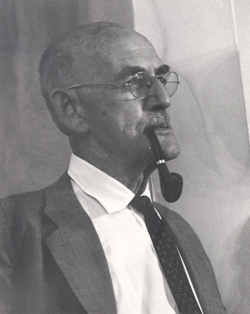

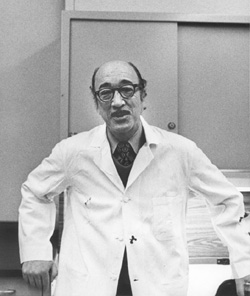

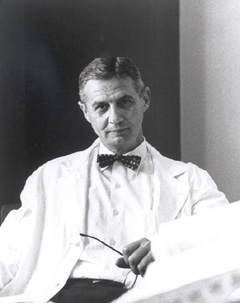

| Philip Shaffer, Abraham Flexner, and Robert Terry in 1950 |

| Three grand old survivors of Washington University’s reform era met at the centennial celebration of Robert Brookings’ birth, February 21, 1950. A special convocation was held in Graham Chapel to confer an honorary degree on Flexner, whose advice and support had been so instrumental to the medical school’s reorganization and growth. |

Interrupted in the 1930s by the Depression, and in the early 1940s by World War II, the medical school’s growth resumed in the 1950s with the construction of the Cancer Research Building , Wohl and Renard Hospitals. During this period, for the first time, generous federal research support supplemented gifts from private donors. In the last forty years, the original 1915 medical school campus has expanded greatly. This growth has been essential to faculty development.

The number of students and professors has steadily increased. In recent years, women and minority students have become a significant presence. After 1965, women’s enrollment expanded from less than 8% in all previous years to virtual parity today. The first African American physician graduated from the medical school in 1962; since then, more than 300 others have received medical degrees.

With the expansion of knowledge, the number of departments has increased to nineteen from the original nine. Today’s physicians use diagnostic and therapeutic techniques unimaginable a century ago. Advances in genetics and molecular biology hold promise for the prevention as well as the better treatment of disease. Students now in training will practice medicine and help make scientific progress through the greater part of the 21st century.

|

These four men – who collaborated in the development of gall bladder visualization in 1923 – took justifiable pride in their achievement. Copher, Graham, and Cole were surgeons; Moore was a radiologist and first head of the Department of Radiology. This new diagnostic technique, accomplished with the help of the Mallinckrodt Chemical Company, inspired Edward Mallinckrodt to endow, with additional funds from the General Education Board, a full-time radiology department. He also gave funds for an Institute bearing his name, which opened in 1931.

Since then, members of the Institute have made major contributions to research, teaching, and patient care. In 1963 it became the site of the first cyclotron located within an American medical center. Among the faculty’s outstanding contributions has been the development of PET (positive emission tomography), which visualizes metabolic activity in different regions of organs and tissues. |

| Dr. Glover Copher, Dr. Evarts Graham, Dr. Warren Cole, and Dr. Sherwood Moore in front of the Mallinckrodt Institute, 1935 |

|

|

Gerty T. Cori, M.D. (1896-1958)

Fellow, Research Associate, Associate Professor, 1931-1946, Professor of Biological Chemistry, 1947-1958

Carl F. Cori, M.D. (1896-1985)

Professor and Head of Pharmacology, 1931-1946

Professor and Head of Biological Chemistry, 1947-1964 |

Natives of Prague, the Coris received medical degrees there in 1920, the year they married. Two years later, they decided to seek better research opportunities in the United States. Appointed to head of Pharmacology in 1931, Carl Cori brought his wife Gerty with him as a full-time research partner. Scientific equals, the Coris had previously encountered opposition to their collaboration. They flourished here for nearly thirty years, in two departments, and worked in brilliant harmony.

Beyond their own distinguished research on glucose metabolism, for which they received the 1947 Nobel Prize, the Coris made their laboratory a mecca for the brightest young scientists in the field. Many later became laureates – among them, Earl Sutherland, who worked in their laboratory as a medical student and won the 1971 Nobel Prize.

Gerty Cori was promoted to the rank of full professor in 1947, the year she became the first American woman Nobelist. Looking back on her career, she commented: “Love for and dedication to one’s work . . . seem to me to be the basis of happiness.” In 1969, Carl Cori recalled that on their arrival, three basic science departments were housed in the South Building. “It has been claimed that there was something mysterious about this building that made for success. Actually, it was the spirit of the school, its organization and its faculty which were largely responsible.” |

|

|

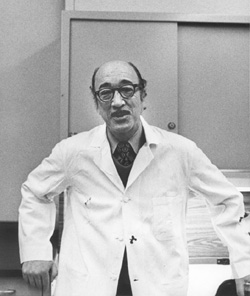

Jacques Bronfenbrenner, M.D., (1883-1953)

Professor and Head of Bacteriology, 1928-1952 |

Born in Russia, Jacques Bronfenbrenner emigrated to the United States in 1909 and became the first full-time head of the Department of Bacteriology in 1928. In addition to his own work on the bacteriophage, he encouraged and trained a new generation of scientists in his discipline.

A colleague remembered: “Dr. Bronfenbrenner was a brilliant man and an effective and popular teacher . . . A generous person, he was quick to recognize talent in others.” Among the young scientists he recruited to the faculty was Alfred Hershey, a Nobel laureate in 1960. |

|

|

Helen Tredway Graham, Ph.D., (1890-1971)

Professor of Pharmacology, 1931-1971 |

Helen Graham came to St. Louis with her husband, Evarts Graham, in 1919. Her early research was done in collaboration with Herbert Gasser and centered on the physiology and pharmacology of peripheral nerves. She continued to work in this area for nearly two decades. At the age of 60, she turned to a new field: the study of histamine. She discovered its function in mast cells and blood basophils and developed sensitive methods for its measurement in body fluids.

A memorable teacher and an outstanding civic leader, the hours she spent in the laboratory remained important throughout her life. The year before her death at the age of 80, she refused a luncheon invitation, saying: “I just can’t afford to take so much time away from my lab in the middle of the day.” |

|

|

George H. Bishop, Ph.D., (1889-1973)

Professor of Physiology and Neurology, 1921-1973 |

In 1921, George Bishop came to the medical school to collaborate with Joseph Erlanger and Herbert S. Gasser. Skill in electrical engineering, innate curiosity, and a highly original approach to science made him a stimulating colleague and teacher. Bishop followed a characteristically independent path and made important contributions toward elucidating sensation, pain, and brain function.

Looking back on his long career, Bishop was grateful for having started out in the laboratory when he and neurophysiology were both young: “In the early days . . . half our time was spent in the shop and most of our guesses were wrong . . . We still had a lot of fun . . . Once in a while, something came out right. Even our departmental mechanic entered into the spirit of investigation along with the rest of us . . ." |

|

|

James L. O’Leary, M.D., Ph.D., (1904-1975)

Professor of Anatomy and Neurology, 1928-1962

Professor and Head of Neurology, 1963-1970

Professor of Neurology, 1970-1975 |

Attracted here by the opportunity to work with George Bishop, James O’Leary received an appointment in the Department of Anatomy in 1928 and later decided to become a neurologist. He did important basic and clinical research on the cerebral cortex, pain, and the diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy. In addition, O’Leary instituted a rigorous neurology residency program and took pride in training a wide range of neuroscience students. In 1945, he took over the Division of Neurology and guided it to departmental status in 1963.

O’Leary saw the challenges of his specialty in a positive light: “There has never been any need for the neurological scientist to feel that his research horizons are about to close in on him. There is much to be done, and we need an abundance of creative talent to do it.”

|

|

Mildred Trotter joined the medical faculty as full-time assistant to Robert Terry in Anatomy in 1924. Succeeding him as course master in 1941, she had taught, over four thousand students by the time she retired in 1966. Beyond her achievements as distinguished teacher, she did significant research on hair and bone growth.

The first woman to achieve the rank of full professor in 1946, she explained her extraordinary rapport with students in a simple observation: “There is nothing so thrilling to watch as growth . . . To be a part of the process brings joy which only my colleagues can understand.” |

|

Mildred Trotter, Ph.D. (1899-1991)

Professor of Anatomy, 1924-1991 |

|

|

Alexis F. Hartmann, M.D., Class of 1922 (1898-1968)

Professor and Head of Pediatrics, 1936-1964 |

| Trained by W. McKim Marriott, Alexis Hartmann continued his biochemical approach to clinical problems in pediatrics. In a series of classic papers, he showed differences in serum electrolyte patterns in dehydration and designed a rational method of fluid replacement. Early experience in the 1920s treating children with diabetes led to a lifelong interest in the disease. Hartmann’s ability to attract a new generation of pediatricians to the field furthered an established tradition of excellence.

|

|

|

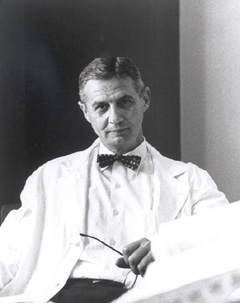

Edmund V. Cowdry, Ph.D., (1888-1975)

Professor of Anatomy, 1928-1975

Professor and Head of Anatomy, 1941-1950 |

Edmund Cowdry joined the faculty in 1928 as head of cytology within the Department of Anatomy and succeeded Robert Terry as head in 1941. Under his leadership, the department became a mecca for cytologists. In the 1930s, he developed an interest in cancer which led to his appointment as director of research at the Barnard Free Skin and Cancer Hospital – and to this hospital’s medical school affiliation. With this relationship came the decision to build a new Barnard Hospital nearby.

A colleague remembered him as “a bull of a man, working at his desk, a handkerchief looped around his neck to catch perspiration . . . one moment editing a manuscript, the next . . . debating the merits of an experimental project.” |

|

|

Edward Gildea, M.D. (1898-1977)

Professor and Head of Psychiatry, 1942-1962 |

| Edmund Gildea arrived four years after the Rockefeller Foundation endowed the Department. A pioneer in biologically-oriented research when this approach to psychiatry was rare, Gildea recruited an able group of younger faculty members who laid the intellectual basis for the school’s leadership in biological psychiatry. During his tenure, Renard Hospital was built to house the department’s research and clinical activities. |

|

|

Shown here examining a patient on professor’s rounds, Barry Wood was the first department head born in the 20th century, in the very year the medical school was reorganized. His arrival on the Executive Faculty at the age of 32 marked a new generation’s influence in academic medicine. During his tenure, he built an outstanding department and inspired a generation of young physicians here. A meticulous clinician and an outstanding educator, he made time to do research on infectious diseases.

In Wood’s view, teaching was a privilege because, as he said: “Medical students are an extraordinary group of people . . . to be associated with them in study and teaching is the most potent kind of stimulus.” |

W. Barry Wood, M.D., (1910-1971)

Professor and Head of Medicine, 1942-1955 |

|

|

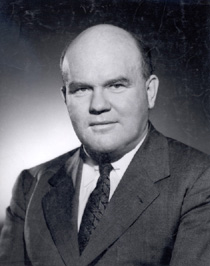

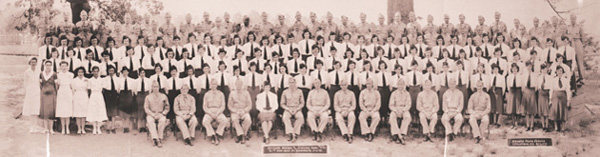

| The Medical and Nursing Staff of the 21st General Hospital, at Fort Benning, Georgia, 1942 |

| The 21st General Hospital was the World War II successor to Base Hospital 21. Like it, all personnel were drawn from the medical school and its associated hospitals. They remained short-staffed during World War II, as they had been in the previous conflict. The 21st served in North Africa, Italy, and France and treated over 65,000 patients. Despite battle conditions, the standard of care was so high that the unit received awards from both the French and American governments. |

|

|

Lee D. Cady, M.D., Class of 1922, (1896-1987)

Commander of the 21st General Hospital, 1943-1946 |

| Shown here receiving the Croix de Guerre in 1945 on the behalf of the unit he commanded from French General Georges Marie Revers, Colonel Lee Cady gave up his private practice during World War II. He led the 21st General Hospital through more than three years of heroic challenges in three different battle theaters. |

|

| Dr. Carl Moore lecturing to medical students in 1943 |

| “Medical School Militarized” read the 1943 St. Louis Post Dispatch headline over this photograph. To aid the war effort, the medical school compressed its curriculum to three years. Here medical students, all in military uniform, are shown attending a lecture in the program which would graduate them as army medical officers. |

|

As pediatrician, medical ethicist, and social activist, Park White exercised an important influence on the medical school. He arrived here in 1920 and served a three year externship at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. A lifelong concern for the health of African American children was evident early in his career. By 1923, he had published an article on racial differences in infant mortality – a problem that concerns pediatricians to this day. From 1945 until 1966 he was Director of Pediatrics at Homer G. Phillips Hospital, then the major St. Louis institution serving minority patients and training minority physicians. Working there to upgrade hospital standards and improve community health, White also served as mentor to African American physicians.

In addition to public activities and a busy private practice, in 1927 he introduced the first course on medical ethics. A poet by avocation, in one verse he evoked children’s joy:

“A whirling circle of rhythmic grace –

Age never planned such a lovely thing!

I think, The Clinic’s a dismal place,

But not when four year olds dance and sing.”

|

|

Park J. White, M.D. (1891-1987)

Professor of Clinical Pediatrics, 1925-1987 |

|

|

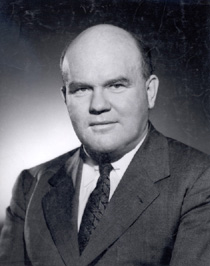

Robert Moore led the medical school through a period of great change in the financing of medical research and education. During his tenure as dean, the federal government became the principal source of grants for training, research, and the improvement of medical facilities. He believed in and worked to secure broad support for academic medicine. Under his leadership, the School of Medicine invited the first African American physicians to join the attending staff in 1949. In addition to his administrative responsibilities, Moore was a well-known pathologist and author of a classic textbook in his field.

In 1951, on the retirement of Philip Shaffer and Evarts Graham, whose distinguished careers brought honor to the School, he spoke words that hold true today: “An institution is only as great as the individual men and women who compose it.”

|

Robert A. Moore, M.D. (1901-1971)

Professor and Head of Pathology, 1939-1954

Dean, 1946-1954 |

|

|

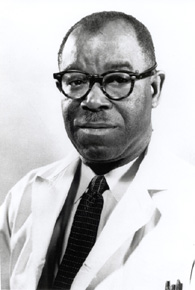

William H. Sinkler, M.D. (1906-1960)

Instructor and Assistant Professor of Clinical Surgery, 1950-1960. |

| William Sinkler served as Medical Director of Homer G. Phillips Hospital from 1941 until 1960. Under his leadership, an affiliation was established with the School of Medicine, and he was named to the clinical surgery staff. His goal was to give minority physicians access to the best training then available. By the time of his death, every department in the hospital had a board-certified physician at its head. |

|

|

William E. Allen, M.D. (1903-1981)

Professor of Clinical Radiology, 1970-1981 |

| A distinguished clinician, in 1935 William Allen became the first African American physician to be certified by the American Board of Radiology. He worked on the Washington University service at Homer G. Phillips Hospital and organized courses to train minority personnel for health care positions. In 1974, he received the American College of Radiology’s Gold Medal for outstanding professional achievement. |

|

|

|

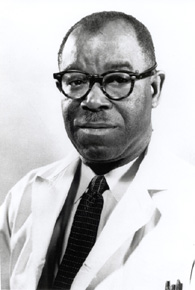

Ernest St. John Simms (1917-1983)

Research Associate Professor of Microbiology, 1971-1983 |

In 1953, Ernest Simms joined the Department of Microbiology as a technical assistant, working with its then head, Dr. Arthur Kornberg. At a time when African Americans seldom had the chance to do original research, Simms’ scientific baptism under the auspices of a future Nobel laureate led to a remarkable scientific career. Despite little formal education, he became a key collaborator in the distinguished achievements of Kornberg’s research team – most notably its work on understanding DNA replication. In later years, he collaborated with Dr. Herman Eisen (Head of Microbiology, 1961-1973) and made important contributions to immunochemistry.

Throughout his career, colleagues appreciated Simms’ intellectual generosity; one remembered: “I think he helped almost every investigator who came through the immunology laboratories . . .” His intelligence, experience, and competence led many to assume that he possessed both a doctorate and a faculty position; this was not the case. However, with enthusiastic support from colleagues, past and present, Simms received promotion in 1971 to research associate professor – a rank only rarely achieved without an advanced degree. While research and teaching remained his principal interests, after 1971 he gave dedicated service to the admission of minority students and served as an invaluable advisor to them.

|

|

Carl Moyer made important contributions to the understanding of blood volume regulation and to the treatment of thermal injury with silver nitrate. This interest led him to establish a Burn Unit at Barnes Hospital in 1964. Deeply concerned about patient care, surgical training, and medical education, he supported the training of minority physicians at Homer G. Phillips Hospital. In 1963, the National Medical Association recognized his contribution with the award of the W. H. Sinkler Memorial Medal. Former house officers long remembered his interest in their development and the generous style of his teaching.

Moyer saw education as a collaborative process and commented: “What is the role of the teacher? He is nothing more than an inspirer and guide in a forest of ignorance, in which he himself is often confused but only rarely lost.” |

Carl A. Moyer, M.D. (1908-1970)

Professor and Head of Surgery, 1951-1965 |

|

|

Margaret Smith, M.D. (1896-1970)

Professor of Pathology, 1929-1970 |

| Prominent in elucidating the pathology of infectious disease, Margaret Smith was best known for her work in isolating the St. Louis encephalitis and salivary gland viruses. She was the first person to propagate the herpes simplex virus in a mouse and discovered the cytomegalic inclusion disease virus. When she began her scientific career in 1922, viruses were no more than an hypothesis. During her lifetime, they assumed scientific reality and became subjects for research to which she made significant contributions. |

|

|

Edward Dempsey, M.D., (1911-1975)

Professor and Head of Anatomy, 1950-1964

Dean, 1958-1964 |

| Here seen working at the electron microscope with students, Edward Dempsey was a distinguished neuroendocrinologist who was among the first to use this instrument for research. During his career, anatomy was transformed from a traditional and descriptive field to a modern science concerned with structure and function at every level of biological organization. Dempsey made contributions to the understanding of behavioral responses in reproduction and worked on the electrophysiology of the forebrain. An effective teacher, he guided many young scientists into research careers. During his years as dean, he was an ardent advocate for the medical school. |

|

|

Sarah A. Luse, M.D., (1918-1970)

Professor of Anatomy and Pathology, 1955-1967 |

| Post-graduate training in electron microscopy and histochemistry brought Sarah Luse to the School of Medicine. Her research centered on developmental alteration of the nervous system and later on artificial and natural membranes. In the early 1960s, she served as director of the Cancer Research Laboratory and Acting Head of Anatomy. Her friendship with students and house officers inspired many to enter research. |

|

|

Carl V. Moore, M.D., Class of 1932, (1908-1971)

Professor of Medicine, 1938-1954

Professor and Head of Medicine, 1955-1971

Dean, 1953-1955

Vice-Chancellor for Medical Affairs, 1964-1965 |

Seen here on rounds with house officers, Carl Moore returned six years after he graduated from the medical school to organize the Hematology Laboratory for the Department of Medicine. Later, he and Barry Wood shared administrative responsibilities, and Moore succeeded him as department head in 1955. In addition to making significant research contributions, Moore served as an inspiring mentor for young physicians. Despite a busy schedule, he was always available to students and accessible to patients. A person of utter integrity, he enjoyed the absolute trust and respect of his colleagues. Late in his career, he was chosen as the first Vice Chancellor for Medical Affairs.

Revered as an exemplary clinician and scholar, Moore explained his philosophy in characteristic terms – helping others: “It seems to me that when it comes time for a man to hang up his hat and quit, what will seem of most importance will not be the stature he has achieved in society or the money he has in the bank, but the contributions he has made to other people. Those of us in medicine enjoy the great good fortune of being surrounded by opportunities to be helpful as physicians, or as teachers, or as investigators.”

|

Joseph Ogura came here as a resident in 1946 and stayed for the duration of a distinguished career. He combined three residencies (in pathology, medicine, and surgery) to build the foundation for his later work. A pioneer in the study of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of sound production and its relationship to respiration, he questioned the prevailing wisdom of standard operating procedures. This skepticism led to his developing less radical surgery for laryngeal cancer.

Nationally and internationally known for his surgical skill, he contributed significantly to the development of his field. Ogura always considered teaching important. In 1967, he said: “Our true function as teachers is to . . . produce people who will surpass us.” |

|

Joseph Ogura, M.D. (1915-1983)

Professor and Head of Otolaryngology, 1960-1983 |

|

|

| James S. McDonnell (1899-1980) at the 1967 “launching” of the McDonnell Medical Sciences Building |

James S. McDonnell was an engineer, aerospace pioneer, and a distinguished educational philanthropist in the Robert Brookings tradition. “Mr. Mac”, as he liked to be called, preferred the idea of “launching” a new building to the earthbound concept of groundbreaking. He served as a generous benefactor and wise counselor to the School of Medicine. For his numerous good offices, the School awarded him, as it had Brookings, the rare tribute of an honorary M.D.

|

| McDonnell Medical Sciences Building, as seen from an interior courtyard |

Completed in 1970 to house the basic science departments, the McDonnell Building signaled a new era of excellence and expansion. Ten years later, with similar visionary generosity, he endowed a new Department of Genetics which bears his name. In 1990, this department was designated one of first national centers for the federally-funded Human Genome Project – and which has subsequently made immeasurable contributions in sequencing the entire genetic code.

Always concerned with human progress, Mr. McDonnell observed in 1963: “Man has achieved the science and technology whereby he can ruin himself on the one hand, or . . . he can consciously proceed with his own creative evolution.”

|

|