Reorganization & Growth, 1909-1929

During these years, Robert Brookings contributed a large portion of his private fortune, marshaled private support, and tapped foundation resources to make the Medical Department a modern school of medicine. By 1905, he had become its major benefactor and was satisfied with its progress. The immediate impetus for change was Abraham Flexner’s preliminary critique of the Medical Department, written in 1909 for the Carnegie Foundation’s national survey. Disturbed by these negative comments, Brookings invited Flexner to return and discuss the school’s deficiencies.

|

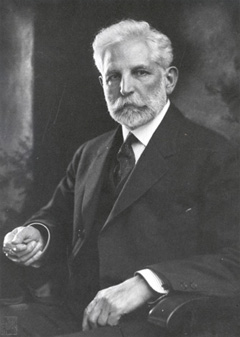

| Robert Brookings at the North Building cornerstone-laying, May 17, 1913. |

| This photograph shows how directly Brookings oversaw the medical school’s progress. In full academic regalia, he – rather than the dean – officiated at the ceremony with the guest speaker, the Reverend James W. Lee, pastor of St. John’s Methodist Episcopal Church, South. At the center rear are two important guests: Dr. William H. Welch, from Johns Hopkins, and Edward Mallinckrodt, a major donor. |

Brookings was soon convinced that nothing less than a full-scale reorganization would bring medical education here to a high standard. A decisive man, Brookings immediately set to work, instituting a national search for outstanding scientists and physicians able to devote themselves full-time to medical education. By 1914, a major part of this new faculty was in place. To insure excellence in clinical training, Brookings negotiated teaching affiliations with the trustees of St. Louis Children’s Hospital and the yet-to-be-built Barnes Hospital . Finally, he raised an endowment from leading local citizens and obtained foundation grants sufficient to make the school independent from tuition as its sole income.

Most important in his success was financial support from the Rockefeller-sponsored General Education Board; Abraham Flexner had been appointed its secretary. In that role, he gave Brookings constant guidance and encouragement. Though the name did not become official until 1918, by 1914 (when the full-time faculty was in place and the new buildings opened) the Medical Department had, in effect, become the Washington University School of Medicine. Under Brookings’ supervision, and in consultation with the faculty, architect Theodore Link (best-known for his Union Station) designed the new physical plant on a spacious site at Kingshighway and Forest Park, a great contrast to the former cramped quarters downtown.

|

| William H. Welch and George Vincent at the Dedication of the New Medical School and Associated Hospitals, April 28, 1915 |

| Among the many distinguished speakers at the elaborate three day ceremonies were Welch, Dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Vincent, President of the University of Minnesota. Welch, then the most influential figure in academic medicine, called the school’s reorganization: “One of the most significant events in the recent history of medical education in America.” |

|

Modernization accelerated with the school’s formal dedication in 1915. In subsequent decades, constant expansion of medical knowledge would lead to additional academic departments and new hospital affiliations. Today’s School of Medicine has grown on this firm foundation of excellence.

| After Brookings agreed to reorganize the medical school according to Flexner’s recommendations, comments published in the 1910 Flexner Report were revised to read: |

“Washington University . . . is . . . marked out as the natural patron of medical education in Missouri. Its importance is bound to be more than local . . . There is abundant evidence to indicate that those interested in Washington University appreciate its ‘manifest destiny;’ it bids fair shortly to possess faculty, laboratories, and hospitals conforming in every respect to ideal standards.” |

|

|

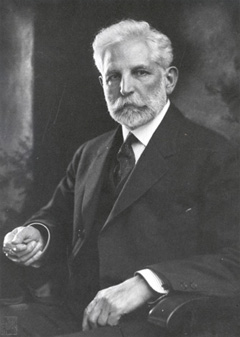

Robert Somers Brookings (1850-1932)

President, Washington University Corporation, 1895-1928 |

At the age of 17, Robert Brookings arrived in St. Louis and went to work as a clerk in the Cupples Woodenware Company. Enormously successful as an entrepreneur, in 1895 he took Samuel Cupples’ advice and turned his energies to educational philanthropy. Though he possessed little formal education, he had acquired a passionate belief in its social value. For the rest of his life, the improvement of Washington University became Brookings’ full-time occupation. He was shocked to hear about Abraham Flexner’s sharp criticism of the Medical Department in 1909. As President of the University Corporation, Brookings rose to the challenge and began to remedy the Medical Department’s problems following Flexner’s advice. In accordance with these changes, the Flexner Report’s comments on Washington University were revised to reflect its promising future. Over the next decade, Brookings used his notable powers of persuasion convincing wealthy friends to join him in financing a modern medical school.

His agenda included a full-time faculty, two affiliated teaching hospitals, and a new location on the edge of the city. Negotiating successfully with donors, professors, hospital trustees, architects and planners, he brought his vision of excellence to life. At the 1915 dedication ceremonies for the new medical school buildings and hospitals, Brookings was honored as "the one man, pre-eminently, whose dream this day is realized.” In response, he set forth a specific goal: “We wish to add our fair share to the sum of the world’s knowledge.” By 1928, when he retired as President of the University Corporation, the School of Medicine was well on its way to fulfilling this aim.

In a 1917 statement defending full-time salaried positions, Brookings eloquently expressed his personal philosophy: “The best service rendered to the world . . . has led men to give themselves without reserve, and has more often been accomplished by financial sacrifice than financial gain.”

|

| Department Heads of the Reorganized School of Medicine, ca. 1910 |

|

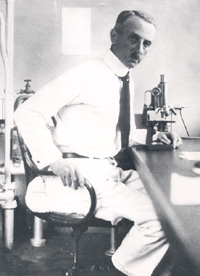

Robert J. Terry, M.D. (1871-1966)

Professor of Anatomy, Missouri Medical College, 1896-1899

Professor of Anatomy, Medical Department, Washington University, 1900-1909

Professor and Head of Anatomy, Washington University School of Medicine, 1910-1941

Professor of Anatomy, 1941-1966 |

The only professor asked to continue as department head after the 1910 reorganization, Robert Terry began his career with the Missouri Medical College. He served as head of Anatomy here for more than three decades. Generations of medical students began their studies under his keen eye.

Renowned for his research on the human skeleton, in 1908 he said: "It is my ambition to have this laboratory productive of the results of advanced study. I wish to share not only in making good physicians, but to add to anatomical knowledge." |

|

|

|

Joseph Erlanger, M.D. (1874-1965)

Professor and Head of Physiology, 1910-1946

Professor of Physiology, 1946-1965 |

| In 1910, Joseph Erlanger agreed to become the first Professor and Head of Physiology. He accepted the position only after Robert Brookings agreed that medical school department heads would form an independent governing body known to this day as the Executive Faculty. In addition to his administrative responsibilities, Erlanger was devoted to excellence in research and teaching. With former student Herbert Gasser, whom he recruited to the faculty in 1916, Erlanger won the 1944 Nobel prize for research on the “properties of nerve fibres.” Their discoveries opened a new era in neurophysiology. |

|

|

Eugene Opie, M.D. (1873-1971)

Professor and Head of Pathology, 1910-1923

Dean, 1912-1915 |

Known for his work in experimental pathology, Eugene Opie conducted fundamental studies on the islets of Langerhans and wrote a standard text on diseases of the pancreas. In addition to distinguished research, he was an effective administrator. In 1912, his colleagues chose him to succeed George Dock as dean. At the 1915 dedication, he remarked:

“A medical school is . . . the atmosphere of its laboratories and wards. The subtle influence which constitutes the relationship between the workers is an essential element of its success.” |

|

|

|

Philip A. Shaffer, Ph.D. (1881-1960)

Professor and Head of Biological Chemistry, 1910-1951

Professor of Biological Chemistry, 1951-1960

Dean, 1915-1919, 1937-1946 |

At 29, the youngest member of the Executive Faculty, Philip Shaffer quickly matured as a scientist and administrator. His research interests centered on biochemical problems relating to blood sugar. He developed a means of purifying insulin for use in childhood diabetes and, with Alexis Hartmann, invented a widely-used test for measuring blood sugar levels. As dean, he consolidated and extended the full-time faculty system. In addition, he was responsible for recruiting such outstanding faculty members as Evarts Graham and Carl and Gerty Cori.

In 1944, when the Nobel prize came to Erlanger and Gasser, he commented: “the high honors bestowed upon our illustrious colleagues reflect a spirit and a policy that this university has consciously cultivated: to seek for its staff those likely to see fundamental problems and to be able to divine ways to solve them. The spirit comes when such men and women labor together and thereby stimulate each other.” |

|

Youth and brilliance characterized them as a group. Henry Pritchett, President of the Carnegie Foundation congratulated Brookings on his choices:

|

“You have certainly got a stunning group of men together; I do not think their like is to be found in America.” |

|

|

Shown here with his staff in 1920 (front row center), George Dock became the Executive Faculty’s senior member in 1910, at the age of 50, and was chosen dean. Famed for clinical acumen and for his ability to apply new methods of laboratory diagnosis, he had been a favorite student of the legendary Dr. William Osler. Like his mentor, Dock was a passionate bibliophile. In addition to administrative and clinical responsibilities, he devoted time to organizing the new medical library. Believing that students should have access to the best historical literature, he enriched the rare book collection with gifts – among them a rare 16th century work from Osler which he donated to celebrate the medical school’s new buildings.

Former students long remembered Dock’s insistence on keen clinical observation; he would ask them repeatedly: “What do you see? What do you see?” |

George Dock, M.D. (1860-1951)

Professor and Head of Medicine, 1910-1922

Dean, 1910-1912 |

|

Working long hours in the library is a medical school tradition. Here students read under portraits of distinguished past faculty members. At this time, the library was located in the North Building where it remained for 74 years until the present Bernard Becker Medical Library was completed in 1989. |

|

| The Medical School Library, ca. 1920 |

|

|

Under the watchful eye of Professor Robert Terry (standing against the wall, at center) first year students dissect in the Gross Anatomy laboratory on the North Building’s 4th Floor – where today’s students continue to take this course. Cases at the rear contain portions of his famous skeleton collection, now in the Smithsonian Institution. |

| The Anatomy Dissection Room, ca. 1921 |

|

Designed by Theodore Link, and named for its donor, Robert A. Barnes, this structure was meant to form a stylistic unity with the medical school buildings across Euclid Avenue. In consultation with the well-known hospital planner Dr. S. S. Goldwater, Link used innovative ideas to create a building with spacious wards, laboratories, and operating rooms. He designed St. Louis Children’s Hospital in a similar fashion, so that these structures would present a harmonious ensemble from Kingshighway to Euclid. In subsequent years, newer buildings covered Barnes Hospital’s original facade. St. Louis Children’s Hospital moved to a larger site nearby in 1984 and its original structures were demolished in the late 1990s. |

|

| Barnes Hospital, 1915 |

|

|

These structures, arrayed from left to right, constituted the new medical school campus built to Robert Brookings’ specifications. Consulting often with the faculty, he wanted these buildings to be highly functional as well as aesthetically pleasing. The North and South Buildings housed basic science departments, the library, and administrative offices. The dispensary or outpatient department was in the West Building, on the other side of Euclid. |

| The Dispensary, Power Plant, North and South Buildings, 1915 |

|

In his dedication speech, Henry Pritchett, President of the Carnegie Foundation, exhorted the faculty to:

|

“breathe life into these laboratories and hospitals a devotion, an energy, an intelligence that may make them live . . .” |

|

Here doctors and a nurse attend patients in the spacious new structure, the successor to the O’Fallon Dispensary in the old Medical Department. This modern and well-equipped facility was a great improvement over the old outpatient clinic. It served patients until 1950, when Wohl Hospital opened and outpatient services were moved there. |

|

| Washington University Dispensary, ca. 1920 |

|

|

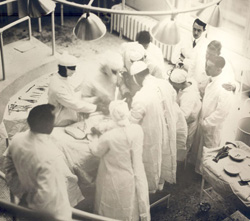

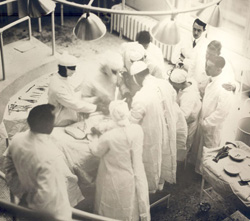

Fred Murphy is seen here in 1914, performing the first operation (an appendectomy) at the newly-opened Barnes Hospital. In 1917, when the country entered World War I, he was named commander of Base Hospital 21, the army medical unit drawn from the School of Medicine and its hospitals. Skeptical about the full-time faculty system, at war’s end he decided not to return to the medical school and was succeeded by Evarts Graham in 1919. |

Fred T. Murphy, M.D., (1872-1948)

Professor and Head of Surgery, 1910-1919 |

|

Here is the original facade of Barnes Hospital draped in patriotic bunting. Nurses in white are gathered on the portico roof. One of six hospitals in a national network organized to serve allied forces during World War I, Base Hospital 21 was sent to France where the staff of 28 doctors and 65 nurses treated some 60,000 patients in little more than a year. During their service, both the School of Medicine and its associated hospitals suffered from greatly reduced faculty and staff. |

|

| Departure Ceremony for Base Hospital 21, May 1917 |

|

|

|

|

| First Women Graduates: Faye Cashatt Lewis, M.D. 1921, Carol Skinner Cole, M.D., 1922, Aphrodite Jannopoulo Hofsommer, M.D., 1923 |

In 1918, the Executive Faculty voted to admit women to the School of Medicine. Faye Cashatt entered that year as a junior transfer student. The only woman in her class, she was the first to graduate with a medical degree from Washington University. Fifty years later, she commented: “In my day, it was a choice between marriage or a career . . . men or women ought to be able to do what they want with their own minds.”

Two other graduates pictured here were the first women classmates to complete the four year course. While they entered together, Aphrodite Jannopoulo received her degree a year later; she lacked a required course on admission. Here, as in other medical schools at the time, women were admitted reluctantly. Their position in the profession was marginal. Yet, despite skepticism about their ability, these women coped well with the rigorous curriculum.

Aphrodite Jannopoulo expressed their courageous pioneer spirit when she wrote in her 1918 diary, “At last my dreams are realized, and I registered at the medical school. Mrs. Cole is the only other woman, so we will have to brave the storm alone.” |

|

|

Shown with his staff in front of the new St. Louis Children’s Hospital, McKim Marriott was noted for his studies of infant feeding and metabolism. Originally trained in biochemistry, this background proved crucial to his later success as a pediatrician. Marriott made his department and its associated hospital a magnet for bright young physicians. In 1918, he became the first department head to accept women house officers. Second from the right is Dr. Martha Eliot, later prominent in the United States Children’s Bureau. |

W. McKim Marriott, M.D. (1885-1936)

Professor and Head of Pediatrics, 1917-1936

Dean, 1923-1936 |

|

Photographed with members of the Department in 1920 the young Evarts Graham (middle, front row) is shown with his older colleagues: the distinguished plastic surgeon Vilray Blair (left), Walter Mills (a radiologist), Nathaniel Allison, and Ernest Sachs, the first professor of neurological surgery (far right). In 1919, recently discharged from the Army, Graham became the first full-time head of Surgery. During a thirty-two year tenure, he exercised a profound influence on the medical school and on his chosen specialty. |

|

Evarts A. Graham, M.D. (1883-1957)

Professor and Head of Surgery, 1919-1951

Professor of Surgery, 1951-1957 |

|

He had a rare ability to apply physiological insights to practical surgical problems; he rightly believed surgical progress depended on this understanding. Instrumental in developing gall bladder visualization in 1923, he performed the first successful lung removal in 1933, thereby opening a new era in thoracic surgery. The training program he established was noted for its high standards and attracted young surgeons from across the country and around the world. Active on the national scene, he led the effort to establish a specialty certifying board and journal. Late in his career, Graham helped elucidate the link between smoking and cancer.

Just before retiring, he commented: “The physiological frontier of surgery is capable of indefinite expansion if we think of a surgeon as one who is interested in something more than cutting and sewing.” |

|

|

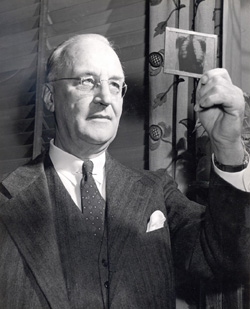

| Joseph Erlanger examining nerve potential recordings, ca. 1925 |

|

Shown here analyzing experimental results, Erlanger remained active in research for many years. His ability as a teacher was outstanding; he wanted students to “imbibe something of the spirit of physiology” from the laboratory course he organized. Herbert Gasser recalled how Erlanger’s lectures had galvanized his interest when he was a student: “the subject matter he presented differed so widely from what was expected that it amounted to a revelation.” |

|

|

Herbert S. Gasser, M.D. (1888-1963)

Assistant and Associate Professor of Physiology, 1916-1921

Professor and Head of Pharmacology, 1921-1931 |

Attracted to medicine by the new idea that medical science could be considered “a discipline in its own right,” Herbert Gasser joined the faculty in 1916 at the invitation of his former teacher, Joseph Erlanger. In 1920, they built their own cathode ray oscilloscope to record and analyze individual nerve impulses for the first time. These experiments were carried out in the basement of the South Building; passing streetcars often disturbed their delicate recordings. This pioneering work won them the 1944 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine – an award which brought international fame to the medical school.

Writing an autobiography in the third person some forty years later, Gasser recalled their first successful experiment: “The most difficult step in opening up a new field had been taken. Ever afterward, Gasser never had any doubt about the direction he would follow.” |

|

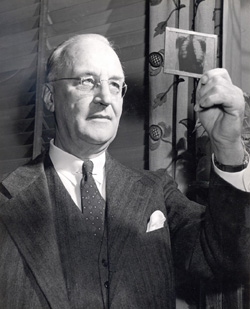

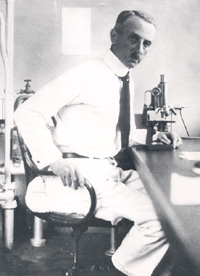

Shown here in a characteristic pose at the microscope, Leo Loeb succeeded Eugene Opie in 1924, and continued a distinguished tradition of experimental pathology. Born in Germany and educated there and in Switzerland, Loeb came to this country in 1910. His research specialties were tissue transplantation and tumor growth; he developed methods for establishing and sustaining in vitro tissue cultures. Called the founder of experimental cancer research, Loeb wrote over four hundred papers, the last when he was over ninety. |

|

Leo Loeb, M.D. (1869-1959)

Professor of Pathology, 1915-1959

Head of Pathology, 1924-1938 |

|

|

David Barr succeeded George Dock as Head of Medicine and built on an established foundation of excellence in teaching, patient care, and research. A firm believer in the full-time system, he worked to make it a success. His own interests were in metabolic disease, a field to which he made major contributions.

Former students remembered: “He was one of a small cadre of American medical giants who helped launch solid, physiologically-oriented clinical research . . . a teacher of singular magnetism, he captured students with his own joy and enthusiasm for doctoring . . . he could tolerate dissent and did not rule by fear . . . He had a refreshing and obvious joy in learning new things . . .” |

David P. Barr, M.D. (1889-1977)

Professor and Head of Medicine,

1924-1941 |

|

Otto Schwarz succeeded his father, Dr. Henry Schwarz, as first full-time department head in 1927, the year the new St. Louis Maternity Hospital opened. A master clinician throughout his career, on retiring from academic medicine in 1940, he rejoined the clinical staff to continue research and practice. |

|

Otto H. Schwarz, M.D. (1888-1950)

Professor and Head of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 1927-1940 |

|

|

In 1923, St. Louis Maternity Hospital made the decision to move from its downtown location and affiliate with the School of Medicine. Four years later, this new building – still in use – was formally dedicated. |

| St. Louis Maternity Hospital under construction, 1926 |

|

|