Concealed Hearing Devices of the 19th Century

“Most hearing aids are of such size and shape that they clearly draw attention to the imperfection of the wearer. This condition is, as we have experienced, enough to make many people shrink back from using such an aid.”

— A. C. Grønbech, M.D., 1891

At the turn of the 19th century, a new trend emerged in the design of mechanical hearing devices. Clumsy and bulky devices such as ear trumpets and long speaking tubes evolved into devices that could be incorporated into everyday items or worn on the person. Public reaction or perceived reaction of others to wearing a noticeable hearing device likely influenced this trend.

|

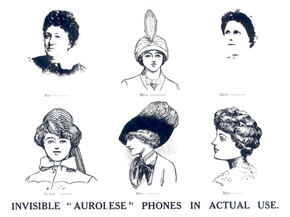

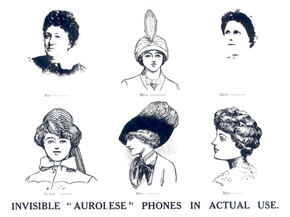

| Invisible Aurolese Phones |

| This F. C. Rein catalog illustration shows a variety of Aurolese Phones and the various ways in which they could be disguised or made “invisible.” |

This new trend in design toward concealment may have encouraged more users to wear hearing devices since they were cosmetically or socially acceptable for public use. It was literally a work of art to combine the elements of disguise and functionality in a form that was aesthetically appealing and yet useful for those with mild to moderate hearing loss. These mechanical hearing devices were elaborately crafted, as evidenced by repousse work, engravings, embossing, paint, and intricate grillwork. Some were enameled a flesh tint or color tinted to match one’s hair. Lace, silk, ribbons, and even feathers often adorned these devices to disguise their function. Despite such artful and ingenious attempts, soothing the vanity of the user while providing acoustic benefit was a daunting task indeed.

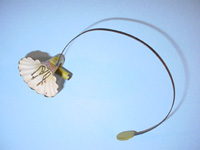

Acoustic Headbands are the earliest known design of a concealed hearing device. They were considered a beautiful way of camouflaging a hearing device within a hairstyle or hat. The early headbands, called Aurolese Phones, made by F. C. Rein, took various forms including simple and irregularly shaped ovoids, barrels, convoluted shells, and even fluted funnels in patterns resembling open flowers. Other headbands had two sound collectors, one for each ear.

|

| The Evolution of the Rein Patent Aurolese Phones |

| This F. C. Rein catalog illustration shows the evolution of the Aurolese Phones models. |

|

| Floral Aurolese Phone |

| This floral Aurolese Phone was made by F. C. Rein about 1802. Over 200 years old, this device still shows its original white and green paint. Despite its fragile appearance and small size, the Aurolese Phone provided an acoustic benefit up to 10 dB over a limited frequency range and was appropriate for a person with a mild hearing loss. |

| View a frequency gain chart for the Aurolese Phone |

| View an Object VR movie of the Aurolese Phone |

|

|

| Barrel Headband |

| Other headband type devices include this “Barrel Pattern” headband made by F. C. Rein, England, about 1845. This headband device is covered with fabric to blend in with a hairstyle or hat. |

|

|

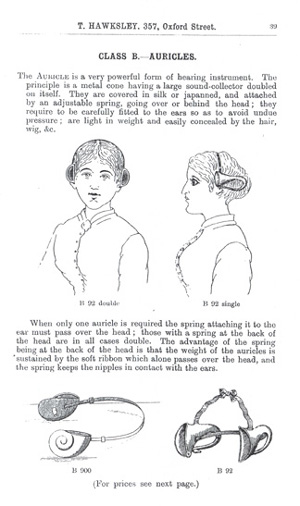

| Auricles from the T. Hawksley & Son catalog |

|

|

| Trumpet Headband |

| This Trumpet headband by F. C. Rein, England, was made about 1850. The metal headband could be worn either on top of the head or around the base of the neck. |

|

|

| Shell-type Auricle Headband |

| This headband by F. C. Rein was introduced around 1830 and was designed for men. Another London firm, T. Hawksley & Co., manufactured similar shell-shaped devices. |

|

|

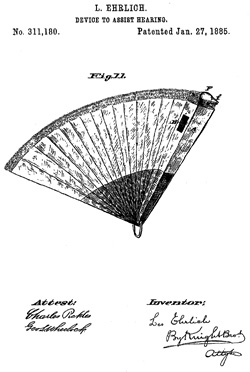

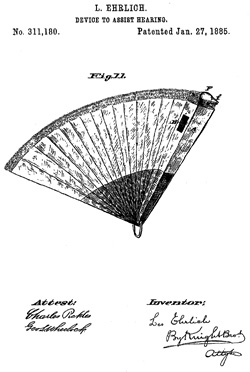

| Hawksley Acoustic Fan |

| This catalog illustration for an acoustic fan was described as “one of the most elegant of the numerous disguised aids.” |

Acoustic Fans were very popular with women in the 19th century. Many such fans were designed to be an elegant way of concealing a hearing device within an everyday object. Several types of acoustic fans were available. Air conduction fans, often made of thin metal and shaped like a partially open fan, were held behind the ear to direct sound into the ear. In some models small trumpets were attached to air conduction fans. One of the most unusual acoustic fans was the bone conduction fan. This fan was a bizarre, yet effective device that used bone conduction to transmit sound. In bone conduction, sound is transmitted to the inner ear via the vibration of the bones in the head, such as the teeth and skull. This contrasts with the usual way that sound is transmitted to the inner ear, namely, through the air.

|

| Air Conduction Fan |

| One common type of acoustic fan had a flat edge that allowed the user to hold the open fan behind the ear using the same principle as a discreetly cupped hand to direct the sound. Although the fan did provide some acoustic benefit, the real purpose was probably to encourage others to speak louder. |

|

|

| Acoustic Fan with Ear Trumpet |

| Some acoustic fans had tiny ear trumpets attached and could be used either open or closed. The Hawksley Catalogue states, “Its power varies according to the size of the instrument which is attached to the fan . . . used with the fan open it gives rather better results . . .” |

|

|

Rhodes Audiphone |

| A bone conduction fan made by R. S. Rhodes is shown in this illustration. Assuming a good set of teeth, this fan provided a benefit of up to 30 dB, a gain comparable to listening to someone speaking from a distance of two feet rather than sixty-four feet. |

| See the patent drawing for the Rhodes Audiphone |

|

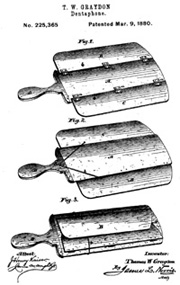

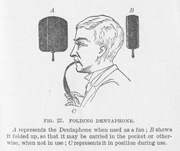

Dentaphone |

|

| This bone conduction fan was patented by T. W. Graydon in 1880. The Dentaphone was a round flat case with a thin diaphragm in the shape of a flat cone at the front center of the case. The user held the case in his hand and a small wooden piece in his mouth was gripped tightly by the teeth. Sound was picked up by the diaphragm, and was passed to the user’s teeth via vibrations through a piece of silk-covered wire. |

|

|

|

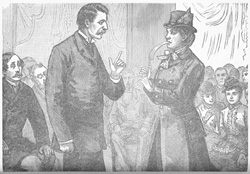

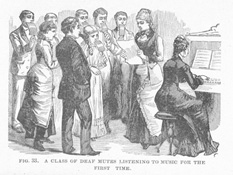

| Audiphone Fan |

| The Audiphone was advertised as enabling “thousands . . . to attend concerts and theatres . . . Music is heard perfectly with it when without it not a sound could be distinguished.” |

“Such graceful forms, not detracting from efficiency,

these artful forms hid one’s deficiency.”

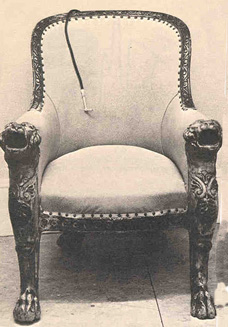

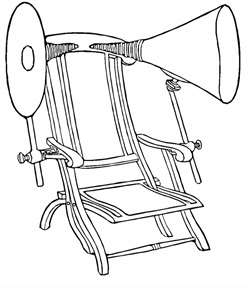

Acoustic Chairs were a clever example of incorporating a hearing device within an everyday object. Some acoustic chairs conveyed sound through the armrests to a hearing tube discreetly placed on the back of the chair leading to the user’s ear. Other chairs simply incorporated ordinary hearing trumpets within the design of the chair with no effort towards concealment. Acoustic chairs or thrones, popular with members of the royalty during the 18th and 19th centuries, allowed users to maintain the charade of normal hearing, with visitors and courtiers being none the wiser.

|

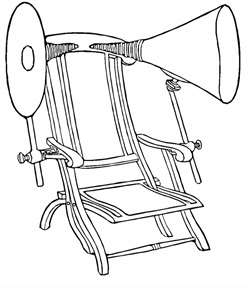

King Goa Chair |

| Perhaps the most ingenious design of an acoustic throne was created by F. C. Rein for King John VI of Portugal (also called King Goa VI ). King John VI used the throne from about 1819 until his death in 1826, while ruling from Brazil. The King’s chair was equipped with a large receiving apparatus concealed beneath the seat. Its hollow arms were elaborately carved to represent the open mouths of grotesque lions and were arranged to act as receivers through which sound was conveyed via a single tube hidden in the back of the chair. Visitors were required to kneel before the chair and speak directly into the animal heads. A replica of the original chair is housed at the Amplivox/Ultratone corporate office in London. |

British aurist and oculist John Harrison Curtis (1778-1860) established the Royal Dispensary for Diseases of the Ear, the first hospital devoted to ear diseases, in 1816. Curtis was a well-known lecturer in the anatomy, physiology and pathology of the ear and the eye. Several editions of Curtis’ A Treatise on the Physiology and Pathology of the Ear were published. The sixth edition in 1836 included this description of his Acoustic Chair:

|

| Curtis’ Acoustic Chair, 1841 |

| The Curtis chair was equipped with a large trumpet alongside the chair to transmit sound to the user’s ear. |

“My Acoustic Chair is so constructed, that, by means of additional tubes, &c., the person seated in it may hear distinctly, while sitting perfectly at ease, whatever transpires in any apartment from which the pipes are carried to the chair; being an improved application of the principles of the speaking pipes now in general use. This invention is further valuable, and superior to all other similar contrivances, as it requires no trouble or skill in the use of it; and is so perfectly simple in its application, that a child may employ it with as much facility, and as effectually, as an adult. It is, moreover, a very comfortable and elegant piece of furniture.

This chair is the size of a large library one, and has a high back, to which are affixed two barrels for sound, so constructed as not to appear unsightly, and at the extremity of each barrel is a perforated plate, which collects sound into a paraboloid vase from any part of the room. The instrument thus contrived gathers sound, and impresses it more sensibly by giving to it a small quantity of air. The convex end of the vase serves to reflect the voice, and renders it more distinct. Further, the air enclosed in the tube being also excited by the voice, communicates its action to the ear, which thus receives a stronger impression from the articulated voice, or indeed any other sound. What first induced me to invent this chair was the fatigue I sometimes experienced in talking to deaf persons.”

Curtis further added that his chair had a great advantage in that the person sitting in the chair was not subjected to the “unpleasant and injurious practice” of bad breath from the speaker since the speaker was required to address the person in the chair from the opposite side. Curtis claimed that there were instances on record of “very baneful and injurious effects” resulting from the practice of speaking into the ear, especially where the breath of the speaker was “tainted.” Henry VIII’s frequent indispositions were reportedly attributed to one of his advisors whispering in his ear.

|

| McKeown Chair, 1879 |

| The McKeown chair was meant to be portable and incorporated two large, adjustable, funnel-shaped trumpets. |

Irish physician William A. McKeown (1844-1904), invented an acoustic chair in the late 1870s. McKeown reasoned that “nine-tenths of a man’s time is spent at home or business; and if during this period I could secure the easy exercise of the function of hearing, the advantage resulting to the deaf would be incalculable.” Home or office furniture, adapted as an acoustic device, would provide the solution. In a 1879 article in The British Medical Journal, McKeown explained how his design allowed for the use of very large tubes, “but it was essential not only to use the large tubes, but have them so arranged that the terminal nozzles should remain in the ears, when introduced, without requiring to be held in place, that they should not press on the ears injuriously, and that the head might be moved without hurting the ears.” The tubes consisted of both rigid and flexible parts in combination. The tubes could be “raised or lowered, shifted backwards and forwards, and revolved so as to admit of the most perfect adjustment.” McKeown’s device enabled deaf persons “to attend to business from which they would be otherwise precluded; for example, a judge on the bench, a lawyer in his chambers, a merchant in his office, may perform their respective duties by aid of an acoustic chair or acoustic writing-table.”

“A deaf person is always more or less a tax upon the kindness and forbearance of friends. It becomes a duty, therefore, to use any aid which will improve the hearing and the enjoyment of the utterances of others without any murmuring about its size or appearance.”

— Hawksley Catalogue of Otacoustical Instruments to Aid the Deaf, 1895

“The deaf are, as a general rule, very sensitive over their infirmity, and hence dislike any instrument which is conspicuous, or makes this condition more apparent; for this reason many other devices have been invented, which seek to conceal this fact, as much as possible . . .”

— James A. Campbell, M.D., 1882

Other unusual hearing aid devices designed to help the deaf appeared during the 19th century. The table vase, beard receptacle, water canteen receptor, and acoustic cane were among such devices. Other devices do not readily fit a particular category, but they all have one thing in common – they were designed to disguise the intended function.

|

|

Water Canteen Receptor |

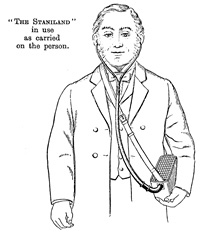

According to Dr. Goldstein in his 1933 book, Problems of the Deaf, this unusual device was called a water canteen receptor. Dr. Goldstein writes that this device was custom-made around 1875 by Thomas Hawksley for a deafened African rubber planter who desired a portable, yet camouflaged, hearing device that could be used while on horseback supervising the workers on his plantation. The device, disguised as a water canteen, was intended to be worn on the body with a shoulder strap for support. The sound was collected at the open grillwork and conveyed through a single rubber tube held by the user to his ear.

In the Hawksley Catalogue, a variation of this device was known as the Staniland model and was used primarily as a tabletop device. There is no mention in the catalog of the origin of the Staniland model, and we have discovered no documents to confirm Dr. Goldstein’s legend.

Can you imagine using this while on horseback, holding the tube to your ear and the reins of the horse at the same time?

View a frequency gain chart for the Canteen Receptor |

|

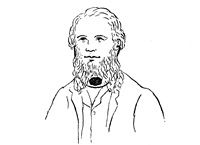

| Beard Receptacle |

The Beard Receptacle is typical of devices designed for men. It was worn with its base resting on the upper part of the chest and its sound collector facing out, hidden under the beard.

Also, at least partially concealed, were rubber tubes leading to each ear. The user had to exercise caution so that the device would not be accidentally pulled while in use, hurting the ears. The manufacturer recommended that a scarf be worn to secure the device. |

|

|

| The Hawksley Catalogue states, “These sketches show a new and very powerful form of the bin-aural instrument to be worn beneath the chin and concealed by the beard; or for ladies by a scarf or tie. Springs inside the tube keep them fitted into the ears.” |

| |

|

|

Hair Receptor |

|

| Women wore a similar device called a hair receptor. This fabric-covered example was designed to be arranged and concealed within the bouffant hairstyle of the prevailing decade. Originally, this receptor was covered with black silk. |

|

| Vase Receptacle |

| This exquisite flower vase receptacle, made by F. C. Rein about 1810, was one of the earliest types of multiple-sound receptors manufactured. Notice the ornate gold grillwork covering each of the six openings, or “receptors,” which act as sound collectors. The white and gold paint is still evident after nearly 200 years. The center of the device is hollow to allow for flowers or fruit to be arranged within. |

|

| F. C. Rein Vase Receptacle |

The photograph above shows the Rein vase receptacle in use. |

|

Hawksley Table Instrument |

| This black metal table instrument is about twelve inches tall. Built about 1875, by Thomas Hawksley, England, it is intended for use on a table. Flowers or fruit were added to conceal the device’s true nature. A silk covered rubber tube leading to the user’s ear was perhaps concealed with a tablecloth, table runner or napkin. This type of device was also known as a table urn, hearing vase, epergne, table receptor, table instrument or multiple-receptor vase. |

| Hawksley TableTop Vase in Use |

|

| This photograph, taken in the library of Central Institute for the Deaf, shows the Hawksley Table Top Vase in use. The user, seated second from left, holds the conversation tube to his ear. The vase, with six funnel openings to collect sound from around the room, sits atop the table. |

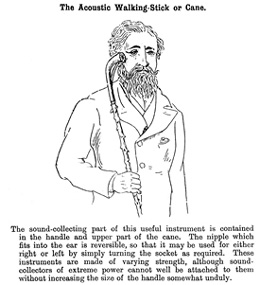

| Acoustic Cane |

|

| This walking cane was the perfect accessory for a dignified gentleman. The handle contains a hollow sound collector that directs the sound to the ear through a reversible earpiece that could be worn in either ear. The user would rest the cane upon his shoulder with the sound receptor in the handle facing the speaker and the earpiece positioned in the ear. Women used umbrellas or parasols with similarly concealed hearing devices. |

|

| A detail of a cane head showing the earpiece positioned for use as a hearing device. When used as a cane, the earpiece swiveled under the handle. |

|

|

| Hawksley catalog illustration of the Acoustic Walking Stick |

|

|

|

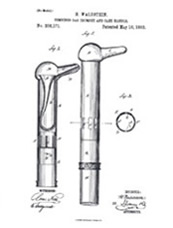

1881 |

1882 |

1885 |

| Patent application illustrations for Acoustic Canes, 1880s |

“The ingenuity and taste of the instrument maker are required to construct mechanical aids to hearing which shall combine gracefulness of form and appearance without detracting from their efficiency, for the burden of deafness is great and the sensitiveness of the sufferers should not be wounded by the necessity of announcing their affliction to the public by having to use instruments either unsightly in form or objectionable in color or material.”

— Hawksley Catalogue of Otacoustical Instruments to Aid the Deaf, 1883

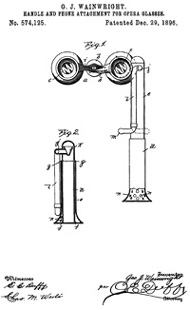

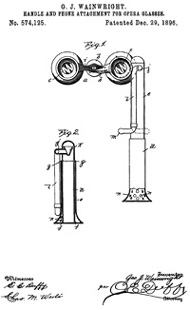

In the 19th century, hearing trumpets were built into opera glasses, binoculars and lorgnettes, combining acoustic benefit with vision enhancement in a single design.

|

© Eriksholm Collection-Oticon A/S |

| Opera Glasses |

| This mechanical trumpet was marketed as an “opera glass lorgnette,” with the trumpet section disguised as the handle. |

|

| Opera Glass Patent |

|

| In a patent application, an inventor of a opera glass hearing device claimed that his device would enable a person to “not only to hear what is going on upon the stage, but also to obtain a good view.” In the 20th century, the concept of combining glasses with hearing devices evolved with the technology. By the early 1960s electronic eyeglass hearing aids accounted for more than half of all hearing aid sales. |

|

| Mourning Trumpets |

|

| One example of a disguised hearing trumpet was the “mourning trumpet,” aptly named as they were covered with black fabric, leather, lace, and ribbon to blend in with clothing typically worn by women in mourning of a loved one. Many styles and sizes of mourning trumpets were available for women during the 19th century and according to the Hawksley Catalogue, they were “suitable for use in public.” |

| |

Courtesy of the Baldwin Collection, Western Michigan University Department of Speech Pathology and Audiology |

|

|

Courtesy of the John Q. Adams Center for the History of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation |

|

Long Tapering Cones from the Hawksley catalog |

| These ear trumpets were “Especially Designed for Ladies’ Use” and “of various shapes and sizes, tastefully trimmed in Leather, Black Silk and Lace to disguise their appearance.” Each model was named after its designer – the “Bradley,” the “Brady,” and the “De Hamel.” The Hawksley catalog further stated that these ear trumpets “are very portable for their strength and are conveniently carried by a silk cord attached to the dress or round the neck.” |

“Sensitive persons, particularly ladies, have an aversion to advertising their affliction in public by the use of many of the usual forms of hearing instruments. To meet this very natural objection, such instruments have been ingeniously combined with fans, parasols, umbrellas, muffs, handbags or reticules, bouquet holders, opera glasses, &c. Other instruments are attached to the head and ears, and may be concealed by the cap, hat, bonnet or hair. . . . For gentlemen, walking sticks and umbrellas of various sizes have powerful sound collectors fitted to them; also dinnerplate holders and field glasses and the inside of the ordinary silk hat.”

— Hawksley Catalogue of Otacoustical Instruments to Aid the Deaf, 1895

A variety of accessories disguising hearing devices were manufactured during the 19th century. Two exquisite examples of accessories or adornments are an artificial concha and a bouquet holder.

|

Artificial Concha |

This beautiful artificial concha, from F. C. Rein, London, about 1830, is made of gold-plated silver with a filigreed grill covering. The concha, custom-designed and molded for an individual user, would have been worn as a self-retaining adornment that could blend in with a hairstyle or jewelry. Acoustic measurements of the concha reveal up to a 13 dB gain over a limited frequency range centered at 1.5 kHz. This gain is considerable for the size of this device, and would benefit a person with a mild hearing loss.

View a frequency gain chart for the Artificial Concha

View an Object VR movie of the Artificial Concha |

|

| Bouquet Holder |

| This ornate, gold plated bouquet holder, made by Thomas Hawksley, London, about 1880, was designed to be worn by a woman on her clothing and concealed with lace, trimming or flowers. The space in the center of the raised dome collected sound and conveyed it to the ear through the rubber tube. |

| View an Object VR movie of the Bouquet Holder |

|

|

| Hawksley catalog Bouquet Holder illustration |

| According to the Hawksley catalog, “This is a pretty device for assisting the best ear in slight cases of deafness. It is attached to the body of the dress, and may be concealed by lace or other trimming, and will contain a few flowers. A very small elastic tube attached to the ear need be the only part apparent. Being especially intended for ladies, although its power varies with its size, it may be made a very useful and elegant acoustic ornament.” |

|

|

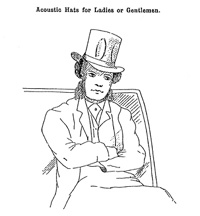

| Hawksley Acoustic Hat catalog illustration |

Hats were another convenient means of concealing hearing devices. Tiny ear trumpets and listening tubes were concealed within or beneath the hat, with the ear pieces discreetly held in place by attached springs and covered with silk or felt.

|

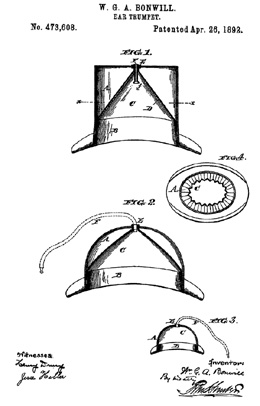

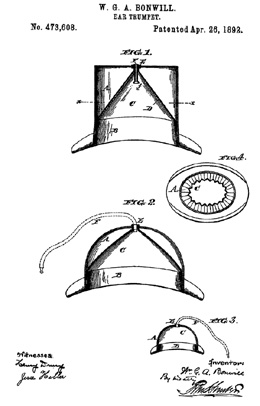

Derby Hat Patent |

| The Derby hat patent was based on the bell-shaped hat acting as a sound receiver with the sound transmitted to the user’s ear via a single acoustic tube protruding from the center of the hat. In the words of the inventor, W. G. Bonwill: “To all appearance the hat is an ordinary one, and a casual observer would not detect the presence of an ear-trumpet within.” |

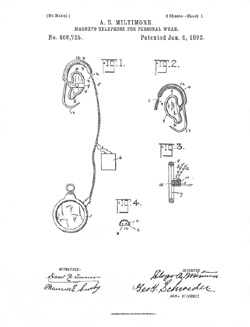

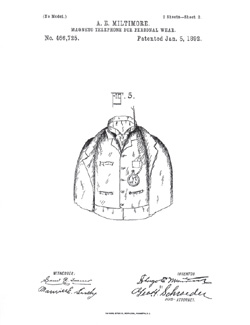

Hearing devices using electricity were conceived during the last decades of the 19th century – though none were successfully completed until the first years of the 20th century. Concealed devices, such as the “Magneto-Telephone for Personal Wear,” featured a transmitter disguised as a “badge or other ornament” that could be worn outside of the clothing or concealed in a pocket.

|

|

| “Magneto-Telephone for Personal Wear” patent drawings |

| This 1892 patent is the earliest known U.S. patent issued for an electric hearing device. However, the device was probably never manufactured. |