Rare Books on Deafness, Hearing, and Hearing Devices

|

The CID-Max A. Goldstein Collection in Speech and Hearing emphasizes works in otology, otorhinolaryngology, speech pathology, and deaf education. Originally assembled by Dr. Max Aaron Goldstein, founder of the Central Institute for the Deaf, the collection was donated to the Washington University School of Medicine Library in 1977. This collection of about 920 volumes of rare and classic books dating from the 15th century on otorhinolaryngology has been called one of the most comprehensive collections in the country for the period 1700 to 1900. Early works on physiognomy, phrenology, and chiromancy are also included in the collection.

Selected rare and classic works from the collection pertaining to means for conveying of sound and amplification of sound are presented in chronological order.

John Bulwer (fl. 1644-1662). Philocophus: or, The Deafe and Dumbe Mans Friend. Exhibiting the philosophicall verity of that subtile art, which may inable one with an observant eie, to heare what any man speaks by the moving of his lips . . . London: Printed for Humphrey Moseley, 1648.

“. . . we have discovered sufficient ground to raise a new Art upon, directing how to convey intelligible and articulate sounds another way to the brain than by the eare or eye; shewing that a man heare as well as speake with his mouth.”

Francis Bacon (1561-1626). Sylva sylvarum. Frankfurt am Main: Schonwetteri, 1665.

| Bacon’s work describes one of the earliest known references to ear trumpets and elaborated on the principle of speaking tubes with comparisons to “ear spectacles.” |  |

| Title page of Sylva sylvarum |

|---|

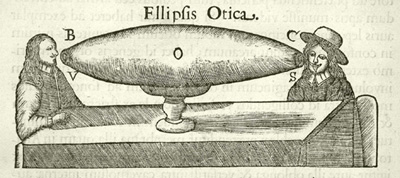

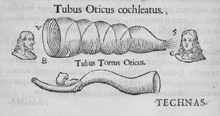

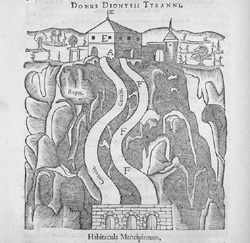

Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680). Phonurgia nova sive conjugium mechanico-physicum artis & naturae paranymta phonosophia concinnatum. Kempten: Rudolph Dreherr, 1673.

Kircher was a Jesuit priest from Germany and later became a Professor of Mathematics at the College of Rome. A true polymath, Kircher was a mathematician, physicist, Orientalist, musician, and physician. While studying at Rome, Kircher built a brass tube leading from his room down to the watchman at the gate to allow for communication of messages. Kircher’s research on sound led him to believe that sound was the earthly counterpoint to heavenly light. To demonstrate this concept, Kircher developed a ‘hearing lens’ or ‘speaking trumpet’ which made distant sounds seem close, just as a telescope does with distant sights.

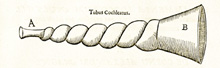

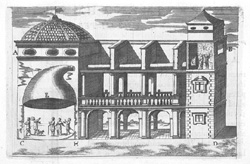

Phonurgia nova was the first known published book to deal with the nature of sound, acoustics and music. The profusely illustrated folio contains the earliest known complete illustrations of devices to convey and amplify sound among the architectural and engineering products related to sound.

Illustrations of speaking tubes and trumpets in Phonurgia nova. The “Ellipsis Otica” (above) is one of the oldest illustrations of a hearing aid.

|

|

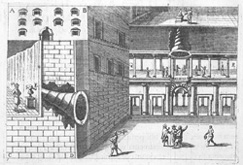

This illustration shows how sound amplification principle was used in dome shaped construction to amplify sound in council halls where it was used to transmit sound to distant points. |

The illustration above left shows how a person in a room inside a building could eavesdrop on people talking in the street outside by means of a sound receiver. Likewise, the illustration above right shows how music being played inside a building could be transmitted and enjoyed by those outside the building.

| This illustration shows how sound could be reflected off an object (in this case, a building), and heard by someone who was unable to see the source of the sound. |  |

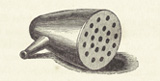

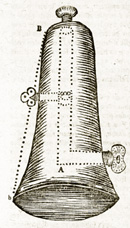

Christoph Stephanus Kazaver. De tuba stentorea: Germ. Das Sprach Rohr . . . praeside Dn. M. Ioh. Henrico Mullero . . . / publico eruditorum examini subjiciet Christoph. Stephanus Kazaver. Altdorf: Typis Iod. Guil. Kohlesii, 1713.

|

De tuba stentorea focuses on the amplification and transmission of sound. The device on the left is similar to a musical instrument; the illustration on the right is of a sound amplification device. |  |

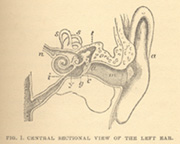

John Harrison Curtis (1778-ca.1860). Treatise on the physiology and diseases of the ear; containing a comparative view of its structure and functions, and of its various diseases, arranged according to the anatomy of the organ, or as they affect the external, the intermediate, and the internal ear. London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones, 1817.

Curtis served as the aurist to the English royalty, authored a number of publications on the physiology and diseases of the ear and invented the Curtis Acoustic Chair. In A treatise on the physiology and diseases of the ear, Curtis stated that patients preferred the French silver ear hearing devices as they were less conspicuous and weighed less than the German silver ears.

Jean Marc Gaspard Itard (1775-1838). Traite des maladies de l’oreille et de l’audition. Paris: Mequignon-Marvis, 1821.

|

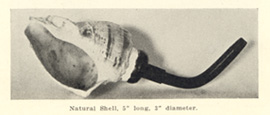

Several hearing devices are described in Itard’s work, including a membrane trumpet, a seashell trumpet and a rod-shaped device using bone conduction. |

John Harrison Curtis (1778-ca.1860). A Treatise on the physiology and pathology of the ear: containing a comparative view of its structure, functions, and various diseases; observations on the derangement of the ganglionic plexus of nerves, as the cause of many obscure diseases of the ear. Together with remarks on the deaf and dumb. 6th ed. London: Longman, 1836.

“To those who wish to hear well, and who disregard the appearance of the trumpet (which, by the by, seems to be the crux surdorum), I would recommend the tin trumpet . . . The cheapest and even the most unsightly, trumpets are often the best; and a common tin one . . . collects more sound, and renders the hearing more acute . . . they may, it is true, be worn under a cap or wig without being seen.”

| Curtis invented this ear trumpet with two apertures, one to be inserted into the meatus and the other into the mouth – the user thus receiving sounds by both the external auditory passage and by the Eustachian tubes. | Curtis credited the invention of this small tin ear trumpet to Don Consul Jovis at Cadiz. Curtis wrote that “in some cases it is found to be of considerable benefit; but still I must, once for all, assure my readers, that it is useless ever to expect to hear so well with a short trumpet, however excellent, as with a long one.” | |

| Curtis claims to have invented this telescoping trumpet “some years ago,” extolling its virtue of collapsing into a small case to be carried in a pocket. |

James A. Campbell. Helps to Hear. Chicago: Duncan Brothers, 1882.

“The deaf are, as a rule, very sensitive over their infirmity, and hence dislike any instrument which is conspicuous, or makes this condition more apparent; for this reason many other devices have been invented, which seek to conceal this fact . . .”

D. B. St. John Roosa (1838-1908). A practical treatise on the diseases of the ear including a sketch of aural anatomy and physiology. 6th edition, revised and enlarged. New York: William Wood and Company, 1885.

|

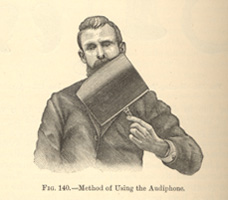

Roosa reports of an instance of watering of the eyes by a patient when using the Rhodes Audiophone as illustrated. |

Laurence Turnbull (1821-1900). A clinical manual of the diseases of the ear. 2nd edition, revised. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1887.

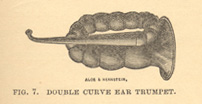

“Ear-trumpets are to the ears what spectacles are to the eyes, but the aid which they render is neither as perfect nor as complete.”

|

|

|

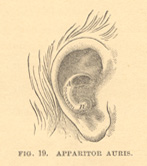

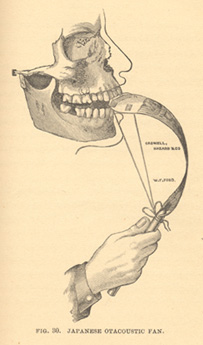

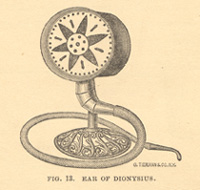

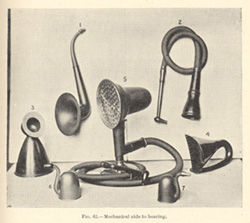

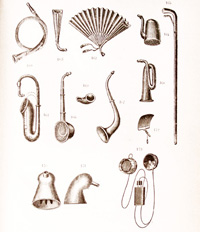

Turnbull’s work contains a variety of illustrations of hearing devices. |

||

|

|

|

Gherardo Ferreri. Manuale di terapia e medicina operatoria. 1899. Roma: Societa editrice Dante Alighiere, 1899.

Adam Politzer (1835-1920). Politzer’s text-book of the diseases of the ear and adjacent organs: for students and practitioners / translated by Oscar Dodd; edited by Sir William Dalby. Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co.; London: Baillière, Tindall and Cox, 1894.

“The number of those who prize ease of social intercourse so highly that they pay no regard to the discomfort and conspicuousness of large ear-trumpets is very small. Nonewithstanding the advantages possessed by large instruments, they are generally discarded on account of conspicuousness in use. The ideal of all deaf people has always been a small instrument which could be worn unobservedly in the ear, and render at the same time the same service as the largest instrument. This problem has not yet been solved, and will not be so easily.”

Seth Scott Bishop (1852-1923). The ear and its diseases: a text-book for students and physicians. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company, 1906.

“No efficient and harmless hearing-instrument for wearing in the ear has yet been devised. Fame and fortune await the inventor of the aural equivalent of spectacles.”

Bishop recounts a conversation with Alexander Graham Bell where Bell related that his discovery of the telephone was related to trying to invent a microphone to aid the deaf. Bishop asked Bell if it were possible to construct an instrument for defective hearing comparable to the lens for defective vision. Bell replied, “I will not say that it is impossible, but in the present state of our knowledge, it is improbable.”

|

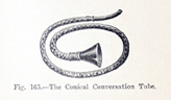

According to Bishop only two hearing devices have proven to be of any practical value. The two are the London Horn and the conical conversation tube as illustrated in Bishop’s work. |  |

Evan Yellon. Surdus in search of his hearing: an exposure of aural quacks and a guide to genuine treatments and remedies electrical aids, lip-reading and employments for the deaf etc., etc. London: Celtic Press, 1906.

Yellon’s work contains rare photographs taken at the turn of the 20th century that show people wearing and using hearing devices.

|

|

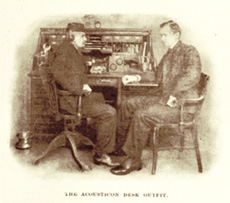

| This photograph shows the Acousticon Desk Outfit in use. | This photograph shows the Acousticon Dining Table Outfit in use. |

“To the sufferer from semi-deafness, an otoacoustical instrument, no matter what its form may be, offers one great objection, namely, it is more or less conspicuous, and immediately draws attention to the user’s infirmity, usually the very thing he or she most desires to avoid. To remedy this drawback as much as is possible, the different instrument makers who specialize in aids for the deaf have placed on the market what are termed ‘disguised aids.’ They take on the form of acoustic fans, walking sticks, books, work boxes, etc. One maker exhibits in his shop window a grand acoustic easy chair, elegantly gilded and nicely upholstered! An invisible aid for the deaf is, as yet, a dream of the remote future, and fair fortune awaits its lucky inventor. Now and again we meet with advertisements of so-called invisible aids for the deaf, but investigation invariably reveals them to be simply tiny trumpets, of value only to keep a closed orifice open; or as artificial ear-drums . . . such advertisements are snares for the unwary and should be regarded with suspicion.”

Thomas Barr (1846-1916). Manual of diseases of the ear. Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1909.

William Guthrie Porter (d. 1917). Diseases of the throat, nose, and ear. Bristol: John Wright & Sons, 1912.

Theodore Heiman (b. 1848). L’oreille et ses maladies. Paris: Steinheil, 1914.

|

Heiman’s work from 1914 contains illustrations of hearing devices, including an early electronic device. |

Max Aaron Goldstein (1870-1941). Problems of the deaf. St. Louis: The Laryngoscope Press, 1933.

Problems of the Deaf is among the premier classic works in the field of deaf education covering a wide range of material related to deafness including anatomy and physiology, research in deafness, rare books, quackeries, hearing devices, phrenology, speech defects, lip-reading, to name a few. Goldstein stated in the foreword that his real inspiration in writing this book was the thought that had activated the best and happiest years of his life: “help the handicapped child.”

| These two hearing devices, a Natural Concha Shell trumpet and an Aurolese Opera Comb by F. C. Rein, were once part of the CID-Goldstein Historic Devices for Hearing Collection (now missing). |  |