Concealed Hearing Devices of the 19th Century

Acoustic Chairs were a clever example of incorporating a hearing device within an everyday object. Some acoustic chairs conveyed sound through the armrests to a hearing tube discreetly placed on the back of the chair leading to the user’s ear. Other chairs simply incorporated ordinary hearing trumpets within the design of the chair with no effort towards concealment. Acoustic chairs or thrones, popular with members of the royalty during the 18th and 19th centuries, allowed users to maintain the charade of normal hearing, with visitors and courtiers being none the wiser.

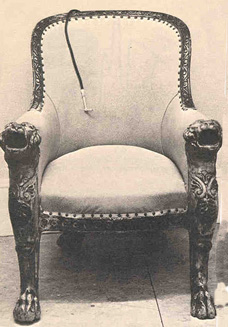

| King Goa Chair | |

|---|---|

| Perhaps the most ingenious design of an acoustic throne was created by F. C. Rein for King John VI of Portugal (also called King Goa VI ). King John VI used the throne from about 1819 until his death in 1826, while ruling from Brazil. The King’s chair was equipped with a large receiving apparatus concealed beneath the seat. Its hollow arms were elaborately carved to represent the open mouths of grotesque lions and were arranged to act as receivers through which sound was conveyed via a single tube hidden in the back of the chair. Visitors were required to kneel before the chair and speak directly into the animal heads. A replica of the original chair is housed at the Amplivox/Ultratone corporate office in London. |

British aurist and oculist John Harrison Curtis (1778-1860) established the Royal Dispensary for Diseases of the Ear, the first hospital devoted to ear diseases, in 1816. Curtis was a well-known lecturer in the anatomy, physiology and pathology of the ear and the eye. Several editions of Curtis’ A Treatise on the Physiology and Pathology of the Ear were published. The sixth edition in 1836 included this description of his Acoustic Chair:

|

| Curtis’ Acoustic Chair, 1841 |

|---|

| The Curtis chair was equipped with a large trumpet alongside the chair to transmit sound to the user’s ear. |

“My Acoustic Chair is so constructed, that, by means of additional tubes, &c., the person seated in it may hear distinctly, while sitting perfectly at ease, whatever transpires in any apartment from which the pipes are carried to the chair; being an improved application of the principles of the speaking pipes now in general use. This invention is further valuable, and superior to all other similar contrivances, as it requires no trouble or skill in the use of it; and is so perfectly simple in its application, that a child may employ it with as much facility, and as effectually, as an adult. It is, moreover, a very comfortable and elegant piece of furniture.

This chair is the size of a large library one, and has a high back, to which are affixed two barrels for sound, so constructed as not to appear unsightly, and at the extremity of each barrel is a perforated plate, which collects sound into a paraboloid vase from any part of the room. The instrument thus contrived gathers sound, and impresses it more sensibly by giving to it a small quantity of air. The convex end of the vase serves to reflect the voice, and renders it more distinct. Further, the air enclosed in the tube being also excited by the voice, communicates its action to the ear, which thus receives a stronger impression from the articulated voice, or indeed any other sound. What first induced me to invent this chair was the fatigue I sometimes experienced in talking to deaf persons.”

Curtis further added that his chair had a great advantage in that the person sitting in the chair was not subjected to the “unpleasant and injurious practice” of bad breath from the speaker since the speaker was required to address the person in the chair from the opposite side. Curtis claimed that there were instances on record of “very baneful and injurious effects” resulting from the practice of speaking into the ear, especially where the breath of the speaker was “tainted.” Henry VIII’s frequent indispositions were reportedly attributed to one of his advisors whispering in his ear.

|

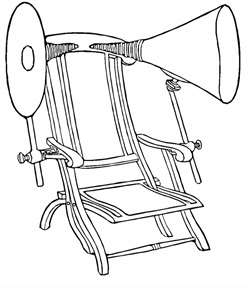

| McKeown Chair, 1879 |

|---|

| The McKeown chair was meant to be portable and incorporated two large, adjustable, funnel-shaped trumpets. |

Irish physician William A. McKeown (1844-1904), invented an acoustic chair in the late 1870s. McKeown reasoned that “nine-tenths of a man’s time is spent at home or business; and if during this period I could secure the easy exercise of the function of hearing, the advantage resulting to the deaf would be incalculable.” Home or office furniture, adapted as an acoustic device, would provide the solution. In a 1879 article in The British Medical Journal, McKeown explained how his design allowed for the use of very large tubes, “but it was essential not only to use the large tubes, but have them so arranged that the terminal nozzles should remain in the ears, when introduced, without requiring to be held in place, that they should not press on the ears injuriously, and that the head might be moved without hurting the ears.” The tubes consisted of both rigid and flexible parts in combination. The tubes could be “raised or lowered, shifted backwards and forwards, and revolved so as to admit of the most perfect adjustment.” McKeown’s device enabled deaf persons “to attend to business from which they would be otherwise precluded; for example, a judge on the bench, a lawyer in his chambers, a merchant in his office, may perform their respective duties by aid of an acoustic chair or acoustic writing-table.”

“A deaf person is always more or less a tax upon the kindness and forbearance of friends. It becomes a duty, therefore, to use any aid which will improve the hearing and the enjoyment of the utterances of others without any murmuring about its size or appearance.”

— Hawksley Catalogue of Otacoustical Instruments to Aid the Deaf, 1895

Continued

<< Previous | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Next >>