Marketing of Hearing Devices

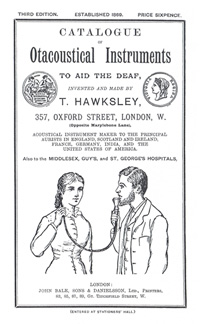

Early marketing efforts for hearing devices in Europe and the United States were confined to trade and medical catalogs with limited mass market advertising.

|

|

||||||

|

|

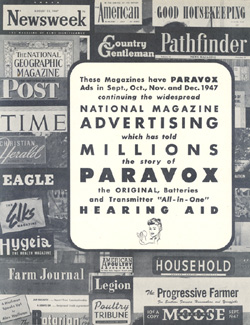

Marketing directed at the consumer was evident by the 1930s and 1940s when hearing aid advertisements were noted in popular magazines such as Life, the Saturday Evening Post, Newsweek, National Geographic and Colliers, and in newspapers.

|

|

||||

|

|

The 1950s was the golden era in the marketing of hearing devices. Marketing for hearing aids was focused on dispelling the perception of bulky hearing aids for the estimated six million hearing impaired individuals in the United States. With the technological advancement of the transistor in the late 1940s and the subsequent miniaturization of batteries, hearing aids became smaller and more powerful – enabling many hearing impaired individuals to potentially benefit from the newer hearing aids.

|

This advertisement from Sonotone shows the evolution of hearing styles from the 1850s to the 1950s. |

Courtesy of Sonotone |

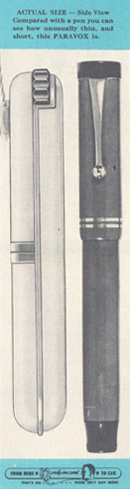

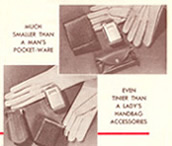

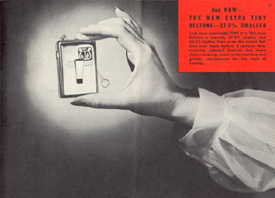

Size was heavily emphasized in marketing of hearing devices to show the ease of use and portability of the new hearing aids. Manufacturers used everyday items such as watches, keys, matches, rulers and cigarettes for size comparison.

|

|

|

“Smaller than your fondest expectations . . .”

— Otarion “Whisperwate” promotional copy, 1950

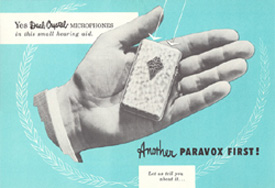

The human hand was a great means of demonstrating size comparison.

And if using everyday objects did not help with size comparison, these advertising inserts based on actual sizes of hearing aids did the trick.

|

Promotional brochures courtesy of Sonotone and Zenith Electronics Corporation |

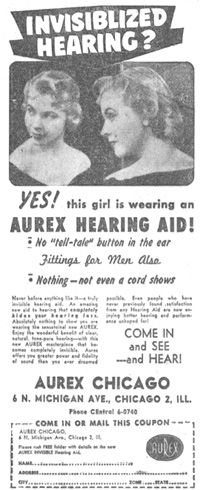

Names of hearing aid models reflected the size theme with names such as “Hidette,” “Secrette,” “Invisible Ear,” “Phantom,” “Midget,” “Hidden Ear,” “Unseen Ear,” “Thumbelina,” “Veri-Small,” and “Hide-A-Way.”

“It has not been many years since deafness and impairment of hearing occasioned ridicule and derisive laughter. The use of the old-fashioned trumpet provoked amusement, and some regarded the condition as a prelude to imbecility or senility. Therefore, it is little wonder that manufacturers of hearing aids today, bent on marketing their wares, make use of advertising with claims, sometimes implicit, often explicit, that ‘nothing shows,’ ‘that “one’s hearing is hidden,” ’ and that nothing is carried around that will reveal a handicapping hearing loss.”

— Council on Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 1951

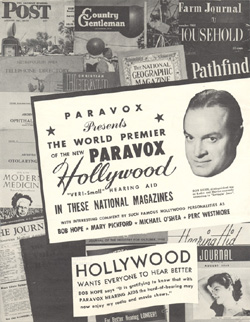

The influence of Hollywood was at its apex after World War II with marketing materials emphasizing glamour and style. Celebrities such as Bob Hope and Mary Pickford were used to tout the uses of hearing aids and many models of hearing aids reflected the Hollywood theme such as “Hollywood Veri-Small” and “Starlet.”

Paravox, Inc. enlisted the help of Hollywood celebrities to promote their hearing aids. A Paravox in-house public relations memo outlines the use of celebrities as a means of reaching out to those who would benefit from a hearing aid:

“. . . it is a step forward in a program to arouse a realization in the hard of hearing people that other people are interested in their problems. If, for example, a hard of hearing person reads that Bob Hope or Mary Pickford have a favorable opinion of hearing aids, isn’t it possible that his or her reluctance to wear an aid may be reduced?”

“It is gratifying to know that with Paravox hearing aids the hard of hearing, everywhere, may now enjoy my radio and moving picture shows.”

— Bob Hope

“I am glad that with Paravox hearing aids more people may now hear dialogue on the screen but more important they may also hear their family and friends.”

— Mary Pickford

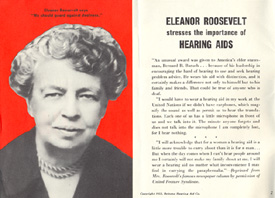

Even Eleanor Roosevelt was used to reach out to millions who could benefit as featured in this Beltone Hearing Aid Company pamphlet.

|

“I will acknowledge that for a woman a hearing aid is a little more trouble to carry about than it is for a man . . . But when the day comes when I can’t hear people around me I certainly will not make my family shout at me. I will wear a hearing aid no matter what inconvenience I may find in carrying the paraphernalia.” |

Courtesy Beltone Electronics Corporation |

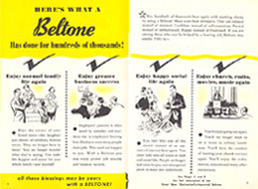

Manufacturers’ claims were limitless. “You look younger-you feel younger . . . helps erase that frown which comes from concentrating . . . permits a relaxed posture – ends that forward thrust of the head, that tendency to sit on the edge of your chair . . . makes school marks better . . . your job safer . . . your sales will go up . . . your domestic life happier . . . you will be happy . . . your children better behaved.”

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of Beltone Electronics Corporation |

|

| This 1952 Beltone brochure promised hearing aid users no less than the opportunity to “say good-bye to the handicaps of hearing loss.” According to the advertising copy, the tiny new Beltone Model L could provide “the difference between happiness and loneliness,” “the difference between self-confidence and self-consciousness,” “the difference between peace of mind and worry,” and “the difference between normal recreation and isolation.” | |

Another marketing angle was to stress the durability of a hearing aid. According to this 1949 advertisement, not only could the Paravox Veri-Small model withstand pressure of 2,400 pounds, it could remain intact after being dropped 600 feet from an airplane.

Not all these claims by manufacturers went unnoticed by the Federal Trade Commission. In the early 1930s the FTC was charged with the responsibility for the regulation of advertising and sales practices of hearing aids. For the time period of 1934 to 1976 the FTC issued sixty-six orders against hearing aid manufacturers for false or misleading advertising claims. Nearly forty percent of these orders were issued in the 1950s for phrases such as:

- “Invisible Hearing Aids”

- “Nothing worn or leading to the ear”

- “Cannot Be Seen”

- “Hides Deafness”

- “Cordless”

- “Out of Sight”

- “Hidden Hearing”

- “Hear Secretly”

- “Even close friends won’t know you’re wearing a hearing aid”

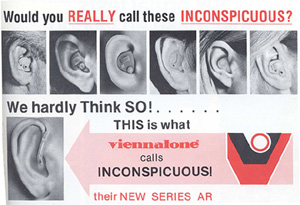

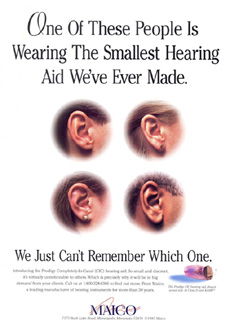

Technological innovation was a primary focus of hearing aid marketing during the latter half of the 20th century. Integrated circuits, directional microphones, and the introduction of zinc air batteries in 1977, along with an increased sense of consumerism led to new strategies for marketing of hearing aids. Miniaturization of hearing aids led to the canal type hearing aids which allowed hearing aids to be completely worn in the ear. More recent developments such as directional microphones, flexible digital programming and adaptive filtering provide users with the best of both worlds – an effective hearing aid that is also virtually unnoticeable.

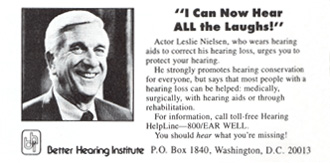

As in the 1950s the use of prominent persons helped in increasing awareness of hearing loss and encouraging others to wear hearing aids. When Ronald Reagan first appeared in public in 1983 wearing an in-the-ear hearing aid, sales of hearing aid increased. Actors such as Lorne Greene, Nanette Fabray, Tom Bosley and Leslie Nielsen were used in advertising campaigns for promotion of healthy hearing and hearing aids.

Durability continued to be emphasized, as in this 1978 advertisement for Oticon hearing aids.

And, as noted in these advertisements, concealment is still a common theme in marketing today.

|

|

|

|