Institutional Roots, 1840-1908

The education of physicians at Washington University began in 1891. Under an ordinance enacted that year, a Medical Department was established which became the Washington University School of Medicine in 1918. This department was the successor to two pioneering institutions: St. Louis Medical College and Missouri Medical College. Founded in the 1840s, they were among the first schools for training physicians in this region. Owned by their faculty and operated for profit, such proprietary schools depended on fees and were correctly perceived as private enterprises. St. Louis Medical College was known as Pope’s College, after its most prominent early dean, Dr. Charles Alexander Pope; the rival Missouri Medical College was known as McDowell’s College in honor of its founder, Dr. Joseph Nash McDowell.

|

| Class of 1879, St. Louis Medical College |

| By this time, medical schools had begun to expand their course of study to an optional three year curriculum. The class of 1879 at the St. Louis Medical College was the first to take advantage of this improvement. Twelve proud graduates pose in formal dress. |

19th century medical schools were run on a very different basis from their modern successors. Today, full-time salaried positions are common, admissions standards are high, and the faculty is expected to do research. A century ago, nearly all faculty members were part-time educators. Professors received fees for the courses they taught and maintained busy private practices. They were not expected to produce original research. Students were admitted to medical schools without rigorous preparation and often without college degrees. Instruction was based almost entirely on lectures; laboratory or bedside learning was rare.

By the 1880s, advances in scientific knowledge made this style of instruction obsolete. Medical students needed to understand new biological facts before they could apply them to patient care. Thus, the germ theory’s acceptance meant not only a revolution in medical practice but an entirely new course of instruction: bacteriology. Lectures alone could not convey this knowledge; students needed supervised laboratory experience. Like other progressive schools of the period, St. Louis Medical College and Missouri Medical College expanded curricula, upgraded admission requirements, and acquired university and hospital affiliations to improve scientific and clinical instruction.

|

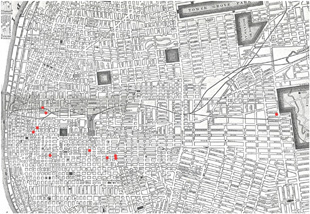

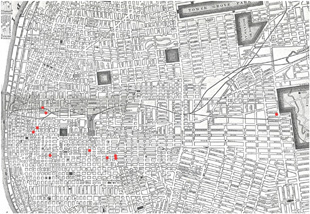

| Locations of Medical Colleges and Medical Department |

| During the years between 1840 and 1891, the forerunners of this medical school changed locations several times. A portion of “Foster’s New Map of St. Louis and Suburbs” (1915) traces the “homes” of St. Louis Medical College, Missouri Medical College, and the Washington University Medical Department, including the present medical campus established in 1914. |

In 1891, the faculty of St. Louis Medical College agreed to affiliate with Washington University – thereby becoming its Medical Department. By 1895, Robert Brookings, a prosperous businessman, had turned to educational philanthropy and made the improvement of Washington University his full-time concern. As president of the University Corporation, he persuaded Missouri Medical College to join St. Louis Medical College’s affiliation with the Medical Department in 1899. In 1904, to upgrade clinical instruction, the Medical Department opened a new Washington University Hospital in the old Missouri Medical College building. This remained the principal teaching institution until Barnes and St. Louis Children’s Hospitals opened in 1914.

Brookings’ concern for consistent educational quality led him to make the Medical Department an integral part of the University. In 1906, the course catalogue announced that "research in medicine and the allied sciences” had become a specific goal. Thus, the faculty took responsibility for producing new knowledge as well as educating physicians. Here and in leading schools across the country, the reform of medical education had emerged as a major concern. By 1908, Washington University’s Medical Department was ripe for change.

|

|

|

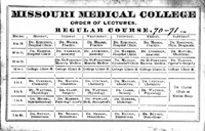

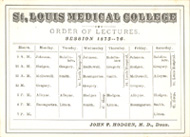

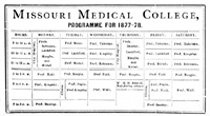

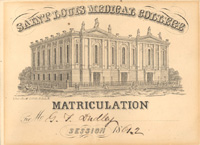

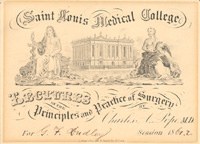

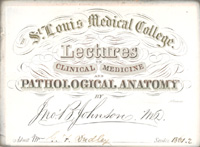

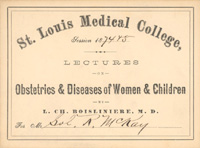

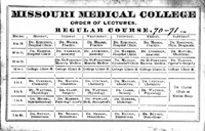

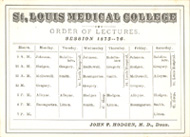

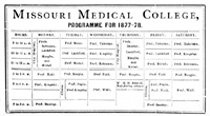

| Course Schedules from the 1870s |

| After the Civil War, students could still obtain a medical degree with only two years’ study, and usually without four years of college education. Courses consisted entirely of lectures, with little laboratory or clinical experience. Though a few classes were held in local hospitals, most doctors saw patients only after they had graduated. |

|

|

|

|

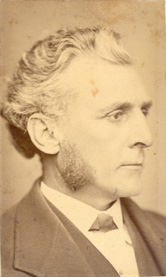

Joseph Nash McDowell, M.D. (1805-1868)

Founder, Missouri Medical College

Dean, 1850-1861, 1865-1868 |

|

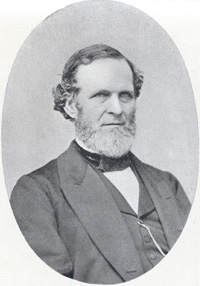

Charles Alexander Pope, M.D. (1818-1870)

Dean, St. Louis Medical College, 1855-1864 |

The dominant figure in the Missouri Medical College’s early history, Joseph Nash McDowell was trained at Transylvania University in his native Lexington, Kentucky. He came to St. Louis in 1840 to organize a medical department at Kemper College and guided the school to independent status as the Missouri Medical College. An anatomist and surgeon, he was dean from 1850 to 1861, when he left to serve in the Confederate Army. After the Civil War, he resumed his former position as dean until his death in 1868.

Famed for his contentious nature and colorful speaking style, McDowell considered location critical to his institution’s success and proclaimed: “We believe the destiny of St. Louis in medicine is not be equaled by any position in Western America." |

|

In 1855, St. Louis Medical College, founded in 1841 as a department of St. Louis University, gained independent status with Charles Alexander Pope as its first dean. Like the best educated doctors of his day, he studied medicine in Europe. In 1854, he became the youngest president of the American Medical Association. In contrast to Dr. McDowell’s irascible character, Pope was known for his urbane gentility. Colleagues remembered him as “a brilliant surgeon and a beautiful operator.” |

|

| The First Missouri Medical College Building, 1840-1850 |

| Missouri Medical College began as the medical department of Kemper College, a short-lived (1840-1845) Episcopalian school. Its first building occupied a bucolic site overlooking Chouteau’s Pond (now situated in the railroad yard north of Ralston Purina Company headquarters). |

| |

|

|

|

| McDowell’s Octagon, 8th and Gratiot Streets |

| The second building for “McDowell’s College” was built between 1848 and 1850 in this distinctive shape. Its fortress-like aspect proved useful during the Civil War when Federal authorities commandeered it for a barracks and prison. During these years, the building suffered heavy damage and required extensive postwar reconstruction. |

|

|

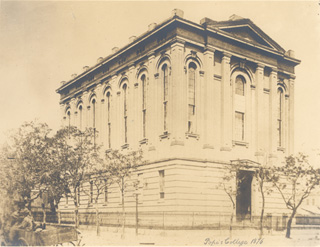

| St. Louis Medical College, 7th and Clark Avenue Building |

| Dr. Pope secured the support of his father-in-law, the real estate magnate John O’Fallon, to construct this graceful neoclassical structure in 1849. In 1851, additions to house the library and a dispensary (named for Mr. O’Fallon) doubled its size but were destroyed by an 1869 fire. In spite of this damage, the building remained the College’s headquarters until 1892. |

|

|

| Missouri Medical College Building, Lucas and 23rd Street |

| In 1873, the college moved to quarters that included facilities for student laboratories; this was its home for the next twenty-one years. One advantage of the location was proximity to St. John’s Hospital, visible in the background. The college boasted that patients could be “carried to the wards . . . into the amphitheatre, for an examination or operation, without the slightest inconvenience.” |

|

|

|

| St. Louis Medical College, 1806 Locust Street, in the 1890s |

| St. Louis Medical College replaced the old Pope’s College Building with a new structure in 1892, the year after affiliating with Washington University. This facility was the Medical Department’s principal building until the reorganized school’s new campus opened at Kingshighway and Forest Park in 1914.

|

|

|

| Missouri Medical College and Washington University Hospital, Jefferson and Lucas Avenue Buildings |

| In 1894, the Missouri Medical College moved to a structure near the St. Louis Post-Graduate School and Polyclinic, an institution it had absorbed four years earlier. Robert J. Terry, a professor there before he joined the Washington University faculty, fondly recalled “the flourishing condition . . . in its new quarters: good laboratories, new equipment, a large clinic, and enthusiastic faculty.” |

|

|

John Thompson Hodgen, M.D.,

(1826-1882)

Professor of Anatomy and Physiology, Missouri Medical College, 1854-1864;

Professor of Anatomy and Physiology, St. Louis Medical College, 1864-1875;

Dean, St. Louis Medical College, 1875-1882 |

| John Hodgen was a student of Joseph Nash McDowell and subsequently became a leading member of the Missouri Medical College faculty. Disruption and damage there during the Civil War led him to join the rival St. Louis Medical College, where he became an influential professor and later dean. Considered a mechanical genius by his colleagues, he was noted for surgical inventions – among them, one that bears his name: the Hodgen splint for treating femoral fracture. |

|

|

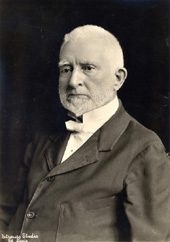

Herman Tuholske, M.D.

(1848-1922)

Professor of Anatomy, Missouri Medical College, 1873-1883;

Professor of Surgery, Missouri Medical College, 1883-1899;

Professor of Surgery, Medical Department of Washington University, 1900-1909;

Professor of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, 1910-1919 |

Born in Germany, Herman Tuholske came to St. Louis in 1865. In addition to academic appointments, he served as the first chief of staff at Jewish Hospital from 1902 to 1919. At the last graduation of Missouri Medical College in 1899, he endorsed the affiliation with St. Louis Medical College under Washington University’s auspices:

“I feel confident that this union of two eminent schools will redound to the glory of our city, to the pride of our state and country. I say with confidence that the coming school will be the greatest medical college in the Mississippi Valley.” |

|

|

Elisha Hall Gregory, M.D.

(1824-1906)

Professor of Anatomy, St. Louis Medical College, 1852-1867;

Professor of Surgery, St. Louis Medical College, 1867-1890;

Professor of Surgery, Medical Department of Washington University, 1891-1902

|

| A student of Dr. Pope, Elisha Gregory was the surgeon-in-chief of the St. Louis Medical College when Pasteur’s germ theory and Lister’s antiseptic procedures transformed the field. At first skeptical of these innovations, Gregory later conducted his own investigations and changed his practice accordingly. An effective teacher, among his most noted students was the pioneer plastic surgeon Dr. Vilray Blair (a member of the Washington University clinical faculty from 1894 to 1955.) Blair called him the “greatest medical lecturer we have had.” |

|

|