The Henry J. McKellops Collection

in Dental Medicine

“In all probability, the most complete dental library in the world is the one collected and left by the late Dr. McKellops and recently purchased by the management of Washington University at St. Louis.”

— Dr. John Campbell, Dental Era, 1905

More than one hundred years later, the McKellops Collection at the Bernard Becker Medical Library remains a lasting monument to an outstanding dental pioneer and bibliophile. These monographs and journals in dentistry and oral surgery represent a sweeping assemblage of works from the early modern era to the 19th century. Ranging from the 16th to 19th centuries, McKellops’s collection was the product of his life-long international study of dentistry as it diverged from medicine into a specialty with its own journals, books, and separate schools.

Upon McKellops’s death in 1901, Adolphus Busch, the brewery millionaire and university benefactor, bought the collection and donated it to Washington University. It was moved to the School of Dentistry in 1912, where it formed the core of the school’s fledgling library. Upon the close of the Washington University School of Dental Medicine in 1991, the library was transferred to the Bernard Becker Medical Library.

Henry J. McKellops (1823-1901) was among the organizers of the Missouri State Dental Association and became its first president in 1865. In 1877 he was named president of the St. Louis Dental Society. The following year he was elected president of the American Dental Association and in 1884 he was named president of the Southern Dental Association.

McKellops was always on the leading edge in dental developments; he introduced the use of the mallet in dentistry, before the Odontological Society of London, and was an early advocate of the use of nitrous oxide as a preferable anesthetic to ether and chloroform. McKellops was also an early advocate of orthodontics and wrote several monographs on the subject.

John Campbell, quoted above, also wrote: “Had Dr. McKellops left no other record to insure the perpetuity of his name than this collection, he surely would be entitled to the highest consideration as a prominent figure in the annals of the dental profession. But aside from being a mere collector of other men’s thoughts, he stood out as the most successful saver of teeth of his day, and his influence will be long felt in this field of activity, which may well be considered the foundation stone of the dental art.”

During McKellops’ lifetime of studies and travels in Europe, he acquired his spectacular collection, along with the assistance of book agents in America, England, and on the Continent. Its range is extraordinary, beginning with Zene Artzney (1532), the first work devoted exclusively to western dental therapeutics.

Zene Artzney : wider allerley Gebrechen vnd Kranckheyt der Zene . . . Getruckt zu Meyntz [Mainz]: bei Peter Jordan, 1532. (Title Page)

Zene Artzney, first published in 1530, is the earliest known book devoted entirely to dental therapeutics. This title page image is taken from the Becker Library’s copy, the 1532 second edition of the book. Written in German, this small volume is one of the early representatives of printed scientific literature in a vernacular language. The text is based on writings by Celsus, Galen, Avicenna, Mesue, and other classical and Arabic medical authors. Copies representing at least ten editions of the book published within forty years prove that it was a successful and much needed publication. It discusses a wide variety of dental topics, including the development and decay of teeth, orthodontics, toothaches, gold foil fillings, tooth extraction, and oral hygiene.

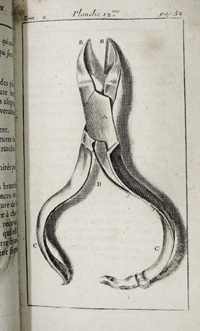

Pierre Fauchard (1678-1761). Le chirurgien dentiste, ou, Traité des dents. 2nd edition. Paris: Chez Pierre-Jean Mariette . . . et chez l’auteur, 1746. (Vol. 2, plate 12) Copper engraving.

The publication of Le chirurgien dentiste (The dental surgeon) in 1728 was a landmark in dental history. For the first time, Fauchard presented in a single work an integrated doctrine of dental science, both theoretical and practical, thus providing dentistry with a solid scientific foundation. Fauchard debunked the myth that toothworms caused decay, and railed against several of the more dubious remedies for toothache. He emphasized the need for more formal training for dental surgeons, insisting that they must have a strong theoretical background, not just a skillful hand. In the section on prostheses, Fauchard described the first attempt to make dentures from an inorganic material, a mixture of bone porcelain and metal. Several of the inventions he cataloged were his own.

The importance of this work was immediately recognized in France, where its publication encouraged his colleagues to share their own knowledge with the dental community, thus creating for the first time a serious exchange of ideas among dentists. Fauchard’s book remained the standard textbook in dentistry for decades, and some of the techniques he first described are still in use today.

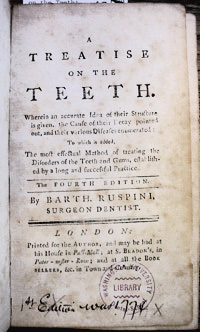

Bartholomew Ruspini, 1728-1813. A treatise on the teeth. Wherein an accurate idea of their structure is given, the cause of their decay pointed out, and their various diseases enumerated : to which is added, the most effectual method of treating the disorders of the teeth and gums, established by a long and successful practice. The 4th ed. London: Printed for the author, 1780? (Title page)

In the introduction to the Treatise, Ruspini proposed “first, to give a distinct and accurate idea of the anatomy of the teeth, and the adjacent parts, to prevent as much as possible those accidents which arise from the ignorance of unskilful practicioners; in this point, who, unacquainted with the structure of the parts, never fail to expose their patients to unnecessary pain, and frequently to dangerous consequences. Secondly; to point out the more immediate causes of the diseases of the teeth, and to shew how they may be mitigated, and in some measure prevented. And thirdly; to introduce and recommend a more general attention than has hitherto prevailed, for the preservation of the teeth, so useful to the purposes of life, and so ornamental, in that part of the creation, where beauty seems to have fix’d her peculiar feat.”

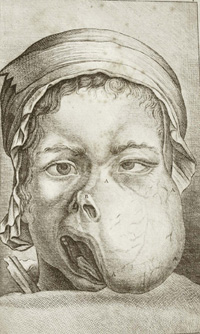

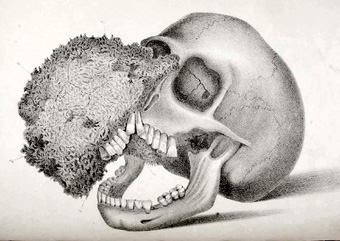

Anselme Louis Bernard Bérchillet Jourdain (1734-1816). Traité des maladies et des opérations réellement chirurgicales de la bouche, et des parties qui y correspondent; suivi de notes, d’observations & de consultations intéressantes, tant anciennes que modernes. Paris: Chez Valleyre l’aîné, 1778. (Vol. 1, plate 4) Copper engraving.

This two-volume treatise was the first specialist book on oral surgery and the most comprehensive work of its kind during the 18th century. It was still highly regarded well into the 19th century. The first English translation appeared in 1849, more than 70 years after Traité des maladies was written. The first volume is devoted to diseases of the maxilla, the second to diseases of the mandible, lips, cheeks, tongue, salivary ducts, and gums. The engraved plates mostly depict dental instruments. However, two plates depict disease – one illustrates exostosis of the bones of the head, and one (pictured) illustrates a tumor.

Benjamin James. A treatise on the management of the teeth. Boston: Charles Callender, 1814. (Engraved title page)

In this work, James warns the public against “floaters,” the itinerant dentists common in early America.

“Most people may be deceived at the time of an operation; though woeful experience in a few months unfolds the deception. The impostor is sought for to make reparation, or to receive merited punishment; but the bird has flown; he is gone to practice his tricks and deceptions among those, who know not his character; until prudence drives him into another seclusion from revenge, into another ‘shoal of gudgeons.’ ”

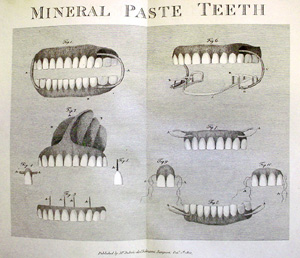

Nicolas Dubois de Chémant (1753-1824). A dissertation on artificial teeth: evincing the advantages of teeth made of mineral paste, over every denomination of animal substance to which is added the advice to mothers and nurses, on the prevention and cure of those diseases which attend the first dentition. London: Printed by John Haines . . . and may be had of the author . . . and of Bosange and Masson, 1816. (Frontispiece) Copper engraving.

Dubois de Chémant perfected the porcelain denture in collaboration with Parisian pharmacist Alexis Duchateau (1714-1792), who was dissatisfied with his own decaying and malodorous ivory dentures and came to Dubois de Chémant for advice. Duchateau produced a suitable denture in 1774, but was unsuccessful in promoting it and abandoned the project. Dubois de Chémant persisted and in 1787, having further perfected the process, obtained a patent under his own name. Duchateau sued unsuccessfully, and Dubois de Chémant announced his discovery to the world in his Dissertation sue les avantages de nouvelles dents et rateliers artificiels incorruptibles et sans odeur. First published in the 1790s, the portrait of Chémant is taken from the 5th edition of the book. In 1791 Dubois de Chémant was granted a patent for his “mineral paste” teeth in England, where he had fled to escape the French Revolution. In the early years of the 19th century, the Wedgewood company supplied porcelain pastes to Dubois de Chémant for the manufacture of artificial teeth.

This copperplate represents the different methods of fixing the teeth, and sets of teeth made of mineral paste. The figures range from a single tooth to a complete set of teeth with gums.

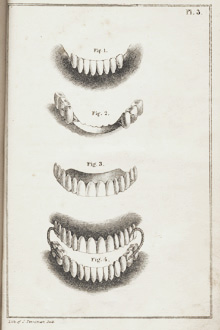

Chapin A. Harris (1806-1860). The dental art : a practical treatise on dental surgery. Baltimore: Armstrong & Berry, 1839. (Plate 3) Copper engraving.

Harris’s The dental art was one of the most influential and most frequently published dental works of the 19th century. First published in 1839, it was reissued thirteen times over the next 60 years.

The professionalization of dentistry in the United States was largely due to the efforts of Harris and his older colleague Horace H. Hayden (1769-1844). In 1840 they co-founded the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, the first institution of its kind in the world. That same year they collaborated in forming the first national association of dentists, the American Society of Dental Surgeons. These two men were also instrumental in founding the world’s first periodical devoted to dentistry, The American Journal of Dental Science, edited by Harris and Eleazar Parmly. The first issue was published June 1, 1839, and included articles by Elisha Barker, Solyman Brown, Parmly, and J. Foster Flagg. When the journal ran into financial trouble in the 1850s, Harris funded it from his own pocketbook, and as a result died a pauper.

Joseph Fox (1775-1816). The natural history and diseases of the human teeth. Philadelphia: Ed. Barrington and Geo. D. Haswell, 1846. (Plate 21) Etching.

Arguably, the earliest systematic dental lectures in Europe were delivered by Joseph Fox in 1799. Fox had great impact on dental practices of his time and even half a century later, however, his theory in physiology and pathology was considered questionable. He was the author of three major dental treatises including The natural history of the human teeth (1803), a seminal work that excels in describing specific operative procedures. His two other works are The history and treatment of the diseases of the teeth, the gums, and the alveolar processes (1806), and The natural history and diseases of the human teeth (1846).

Fox’s most important contribution was in the field of the conservation of teeth developing a ‘fusible metal’ to pour into the tooth cavity. Consisting of bismuth, lead and tin, the main problem with the design lay in its relatively high melting point – equivalent to the boiling point of water – thus making the procedure a particularly painful experience.

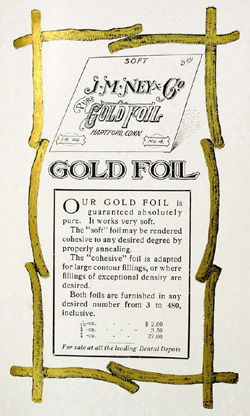

John T. Nolde Dental Mfg. Co. Illustrated catalog and price list of dental supplies. St. Louis: Nolde Dental Mfg. Co., 1905. (Advertisement)

This advertisement for gold foil was published in a book-size catalog of the John T. Nolde Dental Mfg. Company, a dental supply distributor. Nolde’s hard-bound and profusely illustrated catalog is an elaborate and fine work, which offers comprehensive representation of early 20th century dental instruments and accessories.

In a Personal Appeal, printed on the end-sheet before the title page, an anonymous writer described the circumstances of creating such an involved book as a product catalog:

“Our business has grown to such an extent that the pamphlet catalogs issued by various manufacturers do not do justice to the enormous stock we carry. We are practically a clearing-house for everything made for dental purposes [. . .] In the book we have tried to list every single thing we have for sale. Nothing we know of has been omitted, and if you value this book in proportion to [the] amount of work and money we have put into it, we would be glad if you would manifest that appreciation . . .”

Not only could the 1905 audience recognize the typographical and aesthetic values of this volume but also present day users of the book can as well, even though it was basically created to serve such a “painfully practical” industry as dental instrumentation.

| Back to Top | © 2007 Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri |