Classics of Medicine Collection

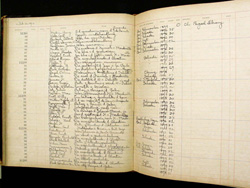

The Classics of Medicine Collection (previously named the General Rare Book Collection) was established in 1912, when the Washington University School of Medicine purchased the working library of Julius Leopold Pagel (1851-1912), a renowned German medical historian. With the support of the Medical Library Committee, especially its chairman George Dock, and the generous monetary donation of Mrs. Benjamin Brown Graham, the 2,500 volumes were bought and shipped from Berlin to St. Louis.

Dock wrote in 1913: “The Pagel library is representative of the collector. [. . .] It is conspicuously the collection of an enthusiastic but frugal student and teacher of medical history, including the historical relations of medicine to human society, and so it contains many works suitable for and essential to the working and reference library of a medical school, and is complete enough and varied enough to form a valuable, even imposing nucleus for a medical-historical seminary or institute. [. . .] The Pagel library provides an equally essential part of medical literature, such as every university medical school should possess or have accessible . . .” (Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, July 1913)

The nineteenth century part of Dr. Pagel’s books became part of the Medical School’s Monuments of Medicine Collection and books published from 1492 to 1820 form now the Classics of Medicine Collection. The latter collection kept Pagel’s well-rounded selection of important authors through the history of medicine until its revolutionary change in the nineteenth century and serves as the main resource for the School’s medical history courses and for historical research.

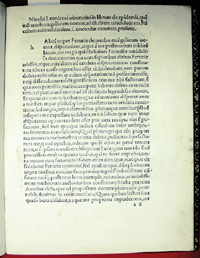

Niccolò Leoniceno (1428-1524). Libellus de epidemia, quam vulgo morbum Gallicum vocant. Venice: Aldus Manutius, June 1497. (A2 recto)

Leoniceno was professor of medicine in Padua, Bologna and Ferrara. This work of his is one of the earliest Renaissance texts on morbus gallicus (syphilis). The book was published by Aldus Manutius, the renowned humanist printer, in 1497. Aldus Manutius was one of the most celebrated printers of all time – his works earned their own category in book collecting, called Aldina. The “King of Printers” name was also honored by the first desktop computer publishing program, Aldus Pagemaker.

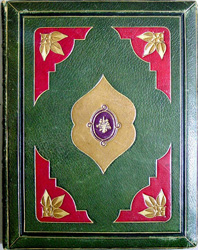

The binding is a 19th century masterpiece.

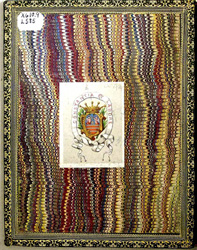

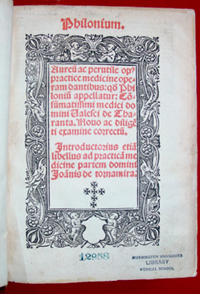

Valesco de Tarenta (fl. 1382-1418). Philonium. Lugduni [Lyons]: Impressum . . . per . . . Jacobum Myt, 1526. (Title page)

A comprehensive late medieval textbook on medicine, Philonium is one of the two extant works written by the Portuguese Valesco. The book had brought significant fame to its author, and he was appointed royal physician in the court of Charles VI of France. Between 1488 and 1500, Philonium went through eleven editions and became one of the most widely used medical texts during that time. New editions were still published until the end of the 17th century.

Remarkable is the bi-color title page with the ornamental woodcut border. The skilled printer, Jacob Myt, certainly “showed off” his artistic technique by creating this well balanced fine-looking page. The white space of the crest (in the bottom panel of the frame) was probably left for the future owner of the book to place an image of his or her own crest.

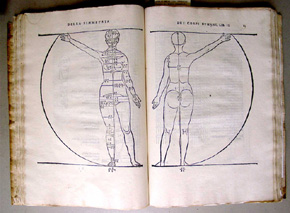

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528). Della simmetria de i corpi humani, libri quattro. In Venetia: Presso Domenico Nicolini, 1591. (Page 63 verso, page 64 recto) Woodcut.

Della simmetria is Dürer’s landmark work on the proportions of the human body. This is an Italian translation (Venice, 1591) which came out very soon after the original German to serve the eager audience of “the land of artists and art.” Note the “Renaissance pose” of the figure similar to the famous Leonardo da Vinci drawing. Dürer had other interests similar to Leonardo’s – besides being an outstanding artist, he too wrote treatises on mathematics, chemistry, engineering, and anatomy.

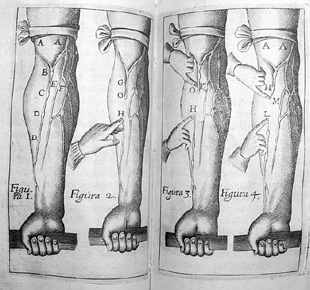

William Harvey, 1578-1657. Exercitationes anatomiae, de motu cordis & sanguinis circulatione. Rotterdam: Arnold Leer, 1654. (Fig. 1-4) Copper engraving.

This small (only 5” x 4”) volume, often referred to as De motu cordis, is a suitable contender to the most highly regarded folio size classic tome in the history of medicine. It contains William Harvey’s “anatomical disquisition concerning the motion of the heart and blood,” a novel theory about blood circulation which has transformed scientific understanding about human physiology ineradicably. Though the views expressed in this book were controversial in Harvey’s time, he was still recognized as a medical authority, and after his death in 1657 his scientific genius was celebrated throughout the European medical community.

After its first edition in 1628, De motu cordis was published numerous times during the 17th century and thereafter. This imprint of 1654 is the first to contain not only De motu cordis but also delayed responses to Harvey’ harsh critic Jean Riolan (1580-1657) and a treatise on the heart by Jacobus de Back (ca. 1594-1658).

Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682). The works of the learned Sr Thomas Brown, Kt., Doctor of physick, late of Norwich. London: Printed for Tho. Basset, Ric. Chiswell, Tho. Sawbridge, Charles Mearn, and Charles Brome, 1686. (Frontispiece) Copper engraving.

This volume contains the most famous writings of the 17th century English physician and author, Sir Thomas Browne. Born in 1602 in London, Browne attended the Universities of Montpellier and Padua, and received his medical degree at Leiden in 1633. Browne moved to Norwich in 1637 and practiced medicine there until his death in 1682. He was knighted by Charles II in 1671.

Browne is best known for his book of reflections, Religio Medici. Browne described the work as “a private exercise directed to myself,” as it contained his thoughts about his religion, the mysteries of God, nature, and man. For several years the journal circulated only as a manuscript among Browne’s friends. It was printed without Browne’s permission in 1642; the following year an authorized edition was published. Religio Medici was an immediate success in England and was soon translated into Latin, French, and Dutch.

In 1646 Browne completed Pseudodoxia Epidemica, or, Enquiries into Very many received Tenets, and commonly presumed truths, often referred to as Browne’s Vulgar Errors. This work addressed the superstitions and popular misconceptions about a number of subjects.

His third book, published in 1658, consisted of two treatises: Hydriotaphia, Urne-Buriall, or, A Discourse of the Supulchrall Urnes lately found in Norfolk, and The Garden of Cyrus, or the Quincunciall Lozenge, or Net-Work Plantations of the Ancients. The first begins with a study of funeral customs that leads into Browne’s reflections on death, immortality and the transience of fame. The second treatise is about the history of horticulture from the Garden of Eden to the Garden of Cyrus in Persia. Browne writes of his fascination with the quincunx, a shape with five parts, which he thought was present everywhere in nature and of the mystic symbolism of the number five.

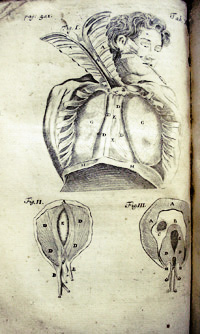

Thomas Gibson (1647-1722). The anatomy of human bodies epitomize’d. Wherein all the parts of man’s body, with their actions and uses, are succinctly describ’d, according to the newest doctrine of the most accurate and learned modern anatomists. The 3rd edition. London: Printed for Awnsham Churchil . . . 1688. (Plate X) Copper engraving.

First published anonymously in 1682, The Anatomy of Human Bodies Epitomiz’d was probably the most successful English anatomical textbook published to date – it was ultimately issued in eight editions. Gibson, the Physician-General to the English army, based his comprehensive text on Alexander Read’s Manual of Anatomy. However, the content was so extensively revised and supplemented Gibson claimed authorship. Gibson listed his principal sources (some 33 titles by 27 authors) which was an uncommon practice at the time.

Leonard da Vinci (1452-1519). A Treatise of painting. London: Printed for J. Senix . . . and W. Taylor, 1721. (Frontispiece and title page)

This treatise is a major source for Leonardo’s work on such topics as proportion, perspective, color, light and shadow, and plant physiology. First English edition.

Johann Wilhelm Weinmann (1683-1737). Phytanthoza iconographia: sive aliquot millium, tam indigenarum quam exoticarum, ex quatuor mundi partibus longa anoorum serie indefesoque studio. Ratisbonae [Regensburg]: per Hieronymum Lentzen, 1737-1745. (No. 371) Mezzotint.

Johann Wilhelm Weinmann’s Phytanthoza is the first botanical book to successfully utilize color-printed mezzotints for its illustrations of plants, fruits, flowers, trees and shrubs. This technology allowed the indication of shades and tones as well as lines of drawings. The 1250 exquisite plates were drawn by George Ehret (1708-1770), and then engraved and partially hand-colored by several artists. It took eight years to complete the grandiose project.

William Cheselden (1688-1752). The anatomy of the human body. The VIIth Edition. London: Printed for C. Hitch & R. Dodsley, 1756. (Plate XVIII) Copper engraving.

Cheselden was one of the leading English surgeons and anatomists of the early 18th century. He was a student of noted anatomist William Cowper (1666-1709) and an apprentice in surgery at St. Thomas’ Hospital. In 1727 Cheselden was the first surgeon to extract bladder stones using the lateral, rather than the suprapubic, approach. The following year Cheselden developed a new method of ophthalmic surgery to treat certain forms of blindness by creating a surgical opening which functioned as an artificial pupil.

The anatomy of the human body was first published in 1713 and became a standard medical text for almost 100 years – it went through sixteen English and American editions through 1806. The 40 leaves of plates illustrating the text were engraved by Gerald Vandergucht. Cheselden’s other noted anatomy text, Osteographia (1733) was an atlas of the bones of the human body, depicting all the bones separately in their actual size.

Hippocrates. Hippocratis Aphorismi. Strasbourg: König, 1756. (Frontispiece) Copperplate.

Hippocrates was a Greek physician born circa 460 BC on the island of Cos, Greece. He became known as the founder of the Hippocratic school of medicine, which greatly advanced the systematic study of clinical medicine. Hippocrates is credited with establishing a medical school on Cos and also with developing an Oath of Medical Ethics which is still used today.

This portrait is from an eighteenth century edition of the Hippocratic aphorisms, published together with the aphorisms of Celsus, the Roman physician (1st cent. AD). The editors, Th. Almeloveen and L. Verhoofd, show the parallels between the two ancient medical texts.

Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771). De sedibus, et causis morborum per anatomen indagatis libri quinque. Patavii: sumptibus Remondinianis, 1765. (Frontispiece and title page)

Morgagni, long time chair of the anatomy department in Padova, is regarded the founder of pathological anatomy. His classification of diseases is the foundation of the modern science of Pathology. Besides medicine he was well versed in archeology and the Classics, and wrote his main work, De sedibus, in Latin. The first edition of this text was published in 1761, when Morgagni was 79 years old. This text was not translated into English until the early 19th century.

| Back to Top | © 2007-9 Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri |