The James Moores Ball Collection

Physician and scholar James Moores Ball (1862-1929) was an avid bibliophile and eminent member of the St. Louis Medical Society. Ball received his medical degree from Iowa State University in 1884, taking further post-graduate courses in New York and Europe. He served as professor of Ophthalmology at the St. Louis College of Physicians and Surgeons from 1894 to 1910, then served as dean and professor of Ophthalmology at the American Medical College.

An interest in medical history underscored Ball’s collection not only of books but also of anatomical specimens, drawings, casts, and ophthalmic instruments. Ball donated the latter collection to the Army Medical Museum [now the National Museum of Health & Medicine] around 1920. His book collection was presented to the St. Louis Medical Society in 1928, where it formed the core of the Society’s rare book holdings. In 1989 the Society deposited the Ball collection at the Bernard Becker Medical Library.

Ball was a prolific author in both the fields of medicine and history. His three monographs truly reflect his scholarly and scientific interests: Andreas Vesalius, the reformer of anatomy (1910), Modern ophthalmology (six editions between 1904 and 1927), and a study of the practice of body snatching, The Sack-em’ Up Men (1928).

The James Moores Ball Collection encompasses rare works on early science and medicine, and is particularly rich in early anatomies from the 16th to 18th centuries. Some of the large folio atlases are most rare – these anatomical atlases are visually stunning collaborations of artist, scientist and engraver. The most magnificent example is the elephant folio of Bernard Siegfried Albinus (1697-1770), Tabulae sceleti et musculatorum (1747). The subsequent period of anatomical figuration after Vesalius, the Albinian period, was named in recognition of Alibnus’ achievement.

Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564). De humani corporis fabrica libri septem . . . Basileae: Ex officina Joannis Oporini, 1543. (Title page) Woodcut.

This title page and the woodcut illustrations within De humani corporis fabrica are among the most famous anatomical illustrations of all time. Here artistic anatomy and typography combine to produce a wonderful work, with scientifically novel and artistically exceptional illustrations of the dissected body in life-like poses.

Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), like most Renaissance anatomists, realized that a sound anatomical and physiological basis was essential to scientific medicine and that its prerequisite was a systematic dissection of the human body. Before the invention and spread of printing, anatomical illustrations were rare and lacking in precision. Too, during many periods, the availability of cadavers was strictly limited and dissections were rarely done. However, cases of autopsy were recorded, especially in Italy, and from 1286 on and anatomical dissection gradually became a fundamental part of medical education.

Vesalius revolutionized the science and teaching of anatomy with the publication of his De humani corporis fabrica. This work provided a fuller and more detailed description of human anatomy than any previous work.

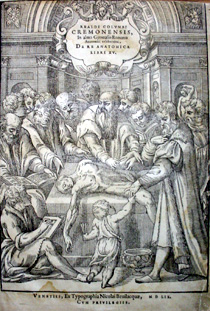

Realdo Colombo (1516?-1559). Realdi Columbi Cremonensis, in almo Gymasio Romano Anatomici celeberrimi, De re anatomica, libri XV. Venetiis: Ex Typographia Nicolai Beuilacquae, 1559. (Title page) Woodcut.

Realdo Colombo was a student of Vesalius and in 1544 succeeded him in the chair of anatomy at Padua. In this first edition of an important anatomical work, Colombo introduced a description of the pulmonary circulation. He probably had no idea of the greater circulation, but his demonstration of the lesser circulation through the lungs secures his place of importance in the history of anatomy, much before the publication of Harvey’s epoch-making book on blood circulation sixty-nine years later.

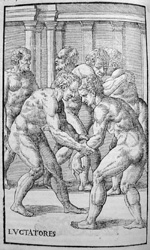

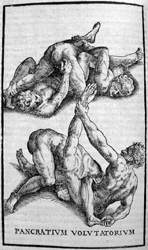

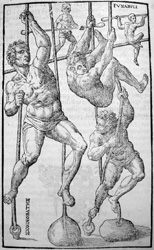

Girolamo Mercuriale (1530-1606). De arte gymnastica libri sex. Tertia editione correctiores, & auctiores facti. Venetiis: Apud Iuntas, 1587. (Pages 104, 106, 148) Woodcuts.

Mercuriale studied medicine at Bologna and Padua before entering the Dominican order at its Milan monastery. He was a proponent of physical education and training, stressing the importance of all forms of exercise to maintaining good health. First published in 1569, De arte gymnastica libri sex was the first complete text on gymnastics. It describes ancient gymnasia and baths and discusses both mild exercises (such as dancing) and more strenuous activities (such as wrestling and boxing). Mercuriale considers the health benefits of proper exercise, and concludes with a section on therapeutic exercises.

The 20 beautiful woodcut illustrations are copies of those designed for the author by Pirro Ligorio and cut by Cristoforo Coriolani.

Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545-1599). De curtorum chirurgia per institutionem. Venetiis: apud Gasparem Bindonum iuniorem, 1597. (Page 10) Woodcut.

Italian surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi is known as the “father of plastic surgery.” He gained experience repairing noses lost in duels or through syphilis. Tagliacozzi developed a technique of nasal reconstruction that used a flap of skin taken from the inner arm of the patient. His De curtorum chirurgia was the first published work on plastic surgery, and it instructed surgeons on how to reconstruct noses and ears. The illustrations depict not only every step in the process of rhinoplasty but also the necessary surgical instruments. Tagliacozzi also devoted a chapter of his text to ancient (Egyptian and Greek) and modern practitioners, citing Galen, Paul of Aegina, Celsus, Alessandro Benedetti, Vesalius, Ambroise Paré, Etienne Gourmelen and Johannes Schenk as authorities.

Regimen sanitatis Salerni, or, The schoole of Salernes regiment of health . . . London: Printed by B. Alsop and T. Favvcet, dwelling in Grab-Street neere the Lower Pumpe, 1634. (Title page with ornamental border)

The School of Salerno was the first known medical school in Europe flourishing from the 8th-12th centuries. Its textbook, the Regimen, contains rules of hygiene and medical treatment, as well as of “good life.”

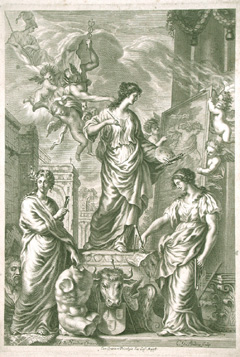

Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688) Teutsche Academie der Edlen Bau-, Bild- und Mahlerey-Künste. Nürnberg: Mitenberger, 1675-79. (Frontispiece) Copperplate.

Joachim Sandrart (1606-1688) was a highly regarded German painter, engraver, and writer on various fields of art. He served as the first director (1662) of the Academy at Nuremberg (the earliest such in Germany).

Sandrart’s treatise, Teutsche Academie der Edlen Bau-, Bild- und Mahlerey-Künste, was published in Nuremberg in 1675-79 and its Latin edition followed in 1683. This treatise was organized into three main parts: Introduction to architecture, painting, and sculpture; Biographies of artists; and Information about art collections.

The book begins with this exquisitely rendered frontispiece, which depicts the goddesses of painting, sculpture, and architecture in the foreground. Mercury and Pallas Athene are also present.

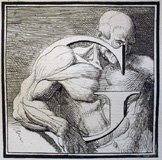

Gerhard Leonard Blasius (1626?-1692). Anatome animalium, terrestrium variorum, volatilium, aquatilium, serpentum, insectorum, ovorumque, structuram naturalem. Amstelodami: Sumptibus viduae Joannis a Someren, Henrici & viduae Theodori Boom, 1681. (Plate XXXIX) Copper engraving.

This comparative anatomy work was the first based on the original and literary researches of a working anatomist. Seventy-eight species of animals are treated in the sixty engraved plates. Blasius, a Dutch anatomist specializing in comparative anatomy, taught medicine at Amsterdam and was also a practicing physician.

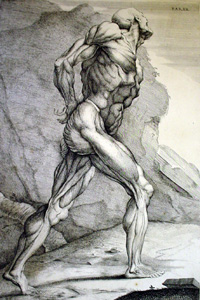

William Cowper (1666-1709). Myotomia reformata, or an anatomical treatise on the muscles of the human body illustrated with figures after the life. London: Printed for Robert Knaplock . . ., William & John Innes, and Jacob Tonson, 1724. (Plate XII) Copper engraving.

Cowper’s Myotomia is considered one of the most beautiful anatomical atlases of the 18th century. It was first published in a much more modest form in 1694, with only ten plates. Cowper worked until his death on a new and expanded edition, which was finally published posthumously under the supervision of Richard Mead (1673-1754). This new edition featured over sixty plates, many in the style of Rubens and Raphael. The text included a long introduction on muscular mechanics by physician and writer Henry Pemberton (1694-1771), the editor of the 3rd edition of Newton’s Principia. Also of note are the ingenious initial letters with anatomical motifs depicting the muscles discussed in the text in which they are placed.

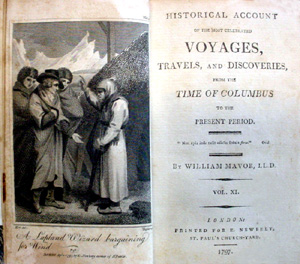

William Fordyce Mavor (1758-1837). Historical account of the most celebrated voyages, travels, and discoveries from the time of Columbus to the present period. Vol. XI. London: printed for E. Newbery, 1797. (Frontispiece and title page)

William Fordyce Mavor was born at New Deer, Aberdeenshire, in 1758. He became the Vicar of Hurley in Berkshire in 1789, and later became headmaster of the Woodstock School. Mavor wrote several books about history, but he also wrote poetry, and published works on education, farming, and stenography. His work, Universal History, Ancient and Modern, from the earliest records of time to the general peace of 1801 consisted of 25 volumes. His Historical Account of the most celebrated voyages, travels and discoveries consisted of 24 volumes.

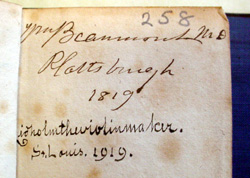

This volume probably became part of the Ball Collection because of its provenance. The flyleaf is signed: “Wm. Beaumont MD, Plattsburgh 1819” and “Lidholm the violinmaker, St. Louis, 1919.” William Beaumont, a 19th century St. Louis physician, is best known for discovering the physiology of digestion.

Valentine Mott (1785-1865). Travels in Europe and the East, embracing observations made during a tour through Great Britain . . . in the years 1834, ’35, ’36, ’37, ’38, ’39, ’40, and ’41. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1842.

Valentine Mott was one of the most prominent American surgeons during the first half of the 19th century and a pioneer in vascular surgery. After obtaining a medical degree at New York City’s Columbia College in 1806, Mott sought further training in London and Edinburgh. After returning to New York City, Mott became professor of surgery at his alma mater, which soon merged with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of the University of New York. In 1826 Mott helped found the Rutgers Medical College, where he served as chair of operative surgery until 1834 when he resigned due to poor health. The following year Mott left for an extended stay in Europe, which lasted seven years. He described his experiences in the three-volume Travels in Europe and the East.

This copy of Mott’s Travels in Europe and the East is unique, with its interleaved etchings, engravings, watercolors, maps, portraits, signatures, and photographs of people, places and events. The first volume includes Mott’s observations on medical science in northern Europe at the time of his travels. He gives details of “extraordinary individuals of my profession, and visits to the more celebrated hospitals and medical schools.” His account of a tour through southern Europe mentions endemial and epidemic diseases, although its emphasis is classic ruins rather than medical matters. The portraits include: Astley Cooper, John Abernathy, William Lawrence, Benjamin Travers, Benjamin Colling Brodie, G. G. Guthrie, Francis Howe, James Gregory, Dugald Stewart, Fitz Greene Halleck, Walter Scott, John Bell, John Herschell, A. Colles, Guillaume Dupuytren, John Hunter, Desault, Civiale, Leroy d’Etioles, A. Dubois, Philippe Ricord, Joseph Souberbielle, F. J. V. Broussais, Bichat, Beclaret, Friedrcus Hoffmannus, Hermann Boerhaave, Dominique Jean Larrey, Napoleon, Ambroise Paré, M. Bouvier, Dr Jenner, Joseph II, Samuel Thomas Sommering, Sir Walter Raleigh, Antonio Scarpa, William Harvey, Hieronymous Fabricius ab Aquapendente, Canova, Paul Mascagni, Pliny the Elder, Johannes Baptista Morgagni, and the author.

| Back to Top | © 2007-9 Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri |