Jacques Jacob Bronfenbrenner (1883-1953)

Jacques Jacob Bronfenbrenner was born in Cherson (Kherson), Ukraine, in 1883. From 1902 until 1906 he studied at the Imperial University of Odessa. He was a member of the Social Revolutionary Party and a follower of Leon Trotsky. In the abortive revolution of 1905, he was among the civilian population who supported the mutiny of the Imperial Black Sea Fleet that was immortalized by Sergei Eisenstein in the film Battleship Potemkin. Marked for arrest by the tsarist regime, Bronfenbrenner fled the Russian Empire and found a haven as a student at the Institut Pasteur in Paris (1907-1909).

While in Paris, he worked in the laboratories of Élie Metchnikoff (Ilya Ilich Mechnikov, 1845-1916), who won the Nobel Prize in 1908 for discovery of phagocytosis and with other Russian émigré scientists, notably Alexandre Besredka. Much of Bronfenbrenner’s early laboratory research was based on Besredka’s fundamental discoveries in antiviral therapies. It is worth noting that the French variants of the Russian or Ukrainian names of Institut Pasteur scientists became more or less official in their publications and other achievements of later life, e.g. “Élie” Metchnikoff and “Alexandre” Besredka. Such a change appears to have been the case with Bronfenbrenner. The “Iakov” of his youth became “Jacob,” but he also must have become known as “Jacques” in Paris and he retained this version as his first name.

Bronfenbrenner’s mentors at the Institut Pasteur made possible his collaboration with Hideyo Noguchi (1876-1928), a Japanese microbiologist working at the Rockefeller Institute in New York. Simon Flexner, director of laboratories at Rockefeller, sponsored Bronfenbrenner’s moving to New York in 1909 and hired him as a research fellow. There he investigated techniques for serum diagnosis of infectious diseases. To further his formal academic training, Bronfenbrenner also enrolled at Columbia University. He received his Ph.D. in 1912 from Columbia under William J. Gies, but his primary teachers remained Besredka and Noguchi.

Bronfenbrenner became a U.S. citizen in 1913. That same year he married Martha Ornstein, an Austrian immigrant who was a historian of science. The couple moved to Pittsburgh, where Bronfenbrenner became head of the research and diagnostic laboratories of the Western Pennsylvania Hospital. His research at this time focused on the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis using biological methods rather than on other chemical or surgical remedies. A son, Martin, was born in 1915 – as the only child of two leftist intellectuals, he grew up to characterize himself as a “red diaper baby.” Martha Ornstein died in an automobile accident that same year, which may have prompted Bronfenbrenner to return with his young son to the East Coast.

In 1917 Bronfenbrenner became an assistant professor of preventive medicine and hygiene at Harvard, a position which allowed him to work toward an advanced degree in public health. In research he concentrated on means of diagnosing bacterial infections (he was particularly interested in botulism) and elucidating other causes of food poisoning. He received a Doctor of Public Health degree from Harvard in 1919. About this same time he married a second time, to Alice Bronfenbrenner, a chemist.

In 1923, Bronfenbrenner returned to Rockefeller, this time to assume the position of “associate member,” which granted him his own laboratory. He began what became his major career focus, namely, research on bacteriophages. Work with these so-called “bacteria eaters” (a term chosen by the principal discoverer, the Canadian Félix d’Hérelle) inspired popular conjecture in terms of potential therapies for infectious diseases – they may have been a source of the fictional discovery celebrated in Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith (1925). Bronfenbrenner directed his investigations toward explaining the physical properties of bacteriophages and how to control and interpret lysis.

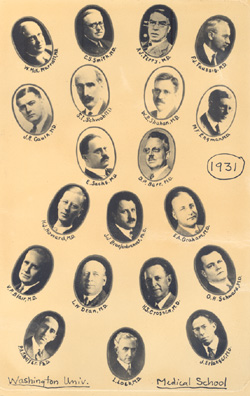

In 1928 Bronfenbrenner accepted the chair of the Department of Bacteriology and Immunology at Washington University School of Medicine (as one of two Rockefeller associates to join the Medical School that year – the other being E. V. Cowdry). In St. Louis he continued his research on purification and quantification of bacteriophages. His laboratories were in what is now known as the West Building. He recruited several brilliant junior faculty members. In time the most famous was Alfred Hershey, who in 1969 would receive the Nobel Prize for identifying the DNA of bacteriophages.

Bronfenbrenner may have been drawn to St. Louis in hopes of establishing a full-fledged school of public health, but it was clear when the Great Depression assaulted the resources of Washington University not long after he arrived that this dream could not be realized. It was difficult enough to maintain the functionality of the 1914-designed laboratories that were inherited from the Pathology Department in those lean times.

Bronfenbrenner did play a major role in the response to a particular public health threat that is now linked by name to his adopted city – St. Louis encephalitis. Among his achievements in this regard was to clarify the difference between the deadly epidemic disease (spread by infected Culex mosquitoes) and streptococcus infections with which it early was misidentified. He later showed that wild mice could play a role in the life cycle of the virus, although common birds were recognized as more often the vectors.

Bronfenbrenner’s son Martin attended Washington University and from these academic beginnings went on to concentrate in – over his father’s opposition at first – economics at the University of Chicago. He was to enjoy a distinguished career with appointments to several distinguished institutions, the last and longest time being at Duke University. Though he thrived in market capitalist circles, Martin more than once confessed nostalgia in his work for his father’s ethics. In 1969, he prefaced an article, “A Working Library on Riots and Hunger” (Journal of Human Resources 4, 1969: 377-90) by writing “This review article is dedicated to the memory of my late father, . . . As an ex-Social Revolutionary and as a medical school teacher of preventive medicine and public health, he would have been an ideal collaborator in this study, and our joint product would have been more than twice as useful than the pages which follow.”

Bronfenbrenner’s abiding concerns with respect to the struggles of his native country found expression again during World War II, when the western Soviet Union was occupied by the Germans and contacts with the United States were in general very difficult. In 1943 he joined with a substantial group of other prominent doctors to establish the American-Soviet Medical Society with the principal aim to exchange medical information. Bronfenbrenner served on the editorial board of American Review of Soviet Medicine, which published English translations of notable findings from 1943 until 1948. When the war against the Nazi regime had been won and tensions between the U.S. and the Soviets increased, leading to the first major Cold War standoffs of 1948, the activities of the society and its journal became unfeasible. They were attacked for disloyally “helping the Russians.” What Bronfenbrenner may have felt about these events is nowhere expressed. It would seem likely that he agreed with the regrets published by the chief editor of American Review of Soviet Medicine, Henry Sigerist, (“On American-Soviet Medical Relations,” 5, 1948, 5-8).

By 1945, the number of scientific papers that Bronfenbrenner published each year curtailed markedly, suggesting that he was no longer active as a bench scientist in his field. He continued his distinguished professional career in other respects. He retained his chairmanship of his department and was active in national and regional societies of microbiologists. It was above all as a teacher and promoter of the work of junior faculty that Bronfenbrenner was long remembered with affection and esteem. St. Louis native and Washington University alumnus Alfred Gellhorn cited this one teacher as the most memorable of several preclinical chiefs who made “medical school a thrilling adventure” (Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 47, 2004, 32-46).

So it was not as a source of major scientific breakthroughs, but as a patient collaborator and verifier of the discoveries of others that Bronfenbrenner made his most lasting contributions. Work with the bacterial culture media, for example, was adapted by his long-time departmental colleague Hiromu Tsuchiya for the study of amebic diseases. (A tenured faculty appointment in Microbiology shielded Tsuchiya, a Japanese citizen, and his research when he might otherwise have been deported during World War II.). Bronfenbrenner’s group also set the stage for genetic discoveries before the formal elucidation of DNA, as in their analyses of phage-bacterium interactions at the molecular level.

Via family connections, Bronfenbrenner’s influence extended in still other directions. His wife Alice became for a time an assistant in the laboratory of Gerty Cori. Son Martin contributed to the U.S.-mandated overhaul of the Japanese tax code during the military occupation of Japan in the late 1940s and early 1950s, which prepared for the spectacular economic recovery of the former enemy nation. Nephew Urie, son of Bronfenbrenner’s brother Alexander, whose immigration to the U.S. was sponsored by the family during its Pittsburgh years, became a noted psychologist at Cornell University and nationally famous as the co-founder of the Head Start Program for disadvantaged pre-school children.

Bronfenbrenner retired from Washington University in June 1952. A former fellow in microbiology, Parker Beamer, had become the head of the department at Bowman Gray School of Medicine. Bronfenbrenner accepted his invitation to become a research professor at the institution, located in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Ill health, however, prevented extensive activity in his new home, and he died August 13, 1953.

Related Resources:

Back to Biographies