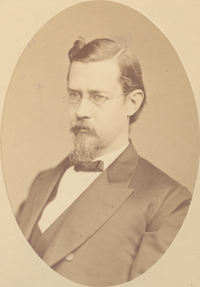

Gustav Baumgarten (1837-1910)

Gustav Baumgarten was born in 1837 in Clausthal (now Clausthal-Zellerfeld), a town located in the Harz Mountains of central Germany known for its extensive silver and copper deposits. Christened Heinrich Ernst Gustav, he was the son of Friedrich Ernst Baumgarten, a surgeon employed by the mining companies. The father emigrated to the United States in 1846 and by 1849 settled in St. Louis, where he sent for his family. The mother, Louise Baumgarten, sailed with Gustav and his two younger sisters on an arduous voyage to New Orleans and from there up the Mississippi, arriving the first day of 1850. Although Friedrich (his name now anglicized as Frederick) made a good start in reestablishing his career in St. Louis, Louise decided that she did not want to live in so raw a frontier city – one indeed recently (1849) devastated by a cholera epidemic and also a fire that had destroyed a substantial portion of its north side neighborhoods. She returned to Germany with her daughters. Gustav remained with his father and was enrolled in a private academy, “E. Wyman’s English and Classical High School.”

Baumgarten commenced his medical education at the Medical Department of St. Louis University in 1854 (better known as “Pope’s College,” after the dean, Charles A. Pope, who owned the college building). While he was a student, in 1855, the department separated from the university and was officially chartered as St. Louis Medical College. The change scarcely made a difference in the curriculum, for the college was already run as a self-standing institution in its own building and for the profit of the faculty. Pope (who was a surgeon) and his colleagues of the time could at best be praised as “skillful operators.” They were inspiring lecturers, but unable to impart deep understanding of cellular and biochemical structure of the human body, the microorganisms attacking it, or how medicinal preparations worked. Baumgarten graduated in 1856. It was a requirement for medical students then to write theses – his subject was “nutrition.” The official copy of this thesis is in the Baumgarten collection and is the only one of its kind that the Library possesses. The work is written in longhand, with extra-wide margins.

At age 19, Baumgarten was not yet ready to embark upon a career in medical practice. Instead, the young doctor journeyed back to his native country in 1857 to enroll at the University of Göttingen, where Frederick had studied. This was the age when many elite American medical students were welcomed at European universities and clinics for postgraduate study. They usually did not make long stops on their tours but enrolled for several weeks or perhaps a term of intensive study. Baumgarten’s year in Göttingen was unusual in that respect. He attended at the university’s Ernst-Augustus Hospital. He of course enjoyed local social connections not shared by other visitors. He joined a fraternity (Burschenschaft). We presume that he visited his mother and sisters in nearby Nordheim. We know that he became romantically involved with a cousin, Aminda Hillegeist, from the Harz Mountains village of Sankt Andreasberg (at least she is identified in correspondence as the daughter of an “Onkel,” the mayor of the village, no less). Gustav and Aminda may have been engaged to be married at this time.

Marriage was postponed, however; Baumgarten proceeded on to enroll for a year at the University of Berlin. He regularly visited the clinics of the Charité Hospital and the ophthalmologic clinics of Albrecht von Graefe. He also studied with Rudolph Virchow, the leading authority of his day in cellular pathology. Discoveries by Virchow and others shifted the focus of medical research in a variety of disciplines to the microscopic level and made it mandatory for universities and hospitals to outfit laboratories with the instruments. Baumgarten thereafter extended his European tour a third year, which began with a term at the University of Vienna, followed by a final semester in Prague. He attended clinics at the large general hospitals in both cities. In Prague he furthered his microscopy under the Czech pathologist Vilem Dušan Lambl, and through him ordered an instrument from a Viennese manufacturer for use in St. Louis. The microscope is made of brass and has three lenses and a variety of other accessories. The European sojourn ended with what he termed “flying visits” to three other universities, in Munich, Würzburg, and Heidelberg.

Baumgarten returned to America in 1859 and entered into practice with his father. He saw patients at the St. Louis Sisters of Charity Hospital and at City Hospital. He also continued his scientific pursuits, writing articles for the St. Louis Medical and Surgical Journal discussing discoveries in cellular pathology by Virchow and others. He interrupted this promising career, however, when the Civil War began. (A story has it that he disappeared from St. Louis without telling his family one day in 1861 to join the Union Navy, surely to avoid his father’s objections.) Baumgarten accepted a commission to serve as a naval surgeon. After a short training assignment in Philadelphia, he spent two of the war years on various ships of the fleet blockading the Gulf Coast ports of the Confederacy. During the last year of the war, he was assigned to the Memphis Naval Hospital.

All during the war Gustav corresponded with Aminda. Within weeks of the final Union triumph, she set forth to join him in America. The bridegroom in the meantime resigned his commission. In June 1865 they were married in St. Louis. It must have been a difficult adjustment for Aminda, but she stayed and made the city her home. The young couple leased a residence directly north of the Court House in what is now downtown St. Louis. They also made excursions to a summer house that the elder Baumgarten had acquired in rural St. Louis County.

Baumgarten’s career flourished. First and foremost he was a private physician with patients of all walks of life and income in the city. In 1878 he and his family moved to a house at 2643 Chestnut Street in what was then a new residential neighborhood west of the city’s commercial core. The first floor of the house included the doctor’s consultation room, study, and library. In this residence the Baumgartens raised three children: Walter, born in 1873; Alma, born in 1877; and Karl, born in 1879. It was an age when even the most eminent physicians made house calls on foot or by horse-drawn carriage. From the end of the Civil War until his death forty-five years later, Baumgarten documented his practice in his appointment books and ledgers.

Throughout his career Baumgarten sought to bring discoveries from abroad and elsewhere to St. Louis. In 1866 he became co-editor of the St. Louis Medical and Surgical Journal and through it published the latest work from Europe. Five years later he resigned the editorship and accepted the first of several of academic positions at St. Louis Medical College. In 1872 the leading faculty members including Baumgarten pooled their own funds to purchase the college building from the Pope estate. From 1872 to 1887 Baumgarten was professor of physiology and medical jurisprudence; from 1887 to 1892, professor of special pathology and therapeutics. He was among the faculty assenting to the affiliation of the college with Washington University in 1891. His last teaching appointment was as professor of medicine. He also served briefly as dean, 1899-1900, the academic year when the college merged with Missouri Medical College and became known simply as Washington University Medical Department.

Not until relatively late in Baumgarten’s career did the college and university provide laboratories for experimental work by its faculty and he personally had no other means to develop a formal research program. Baumgarten did, however, keep abreast of diagnostic advances and to publish reviews of findings. For example, he contributed three articles to a medical encyclopedia, the nine volume Reference Handbook of the Medical Sciences, published in 1885. Two are on the physiology of circulation, concerning respectively uses of the sphygmograph and cardiographs; a third discusses “diffuse affections of the kidney.” Baumgarten also published articles in medical journals throughout his years as a medical educator.

An important aspect of Baumgarten’s life inherited from his father and continued from his student days was enthusiastic participation in professional and social organizations. He was a pillar of the German Medical Society of St. Louis (Deutsche medicinische Gesellschaft), later the Society of German Physicians (Verein deutscher Aerzte), and several of his published papers were composed as addresses in his native language and then translated and reworked in English. He was a member of the St. Louis Society of Internal Medicine and the St. Louis Medical Society. He became president of the Association of American Physicians in 1899 and was a member of other national medical societies. William Osler, arguably the most distinguished internist of the era, corresponded with his colleague and once referred to St. Louis as “Baumgarten’s town.”

Among the most interesting facets of the Baumgarten papers are the many letters and photographs that document the great efforts of family members in St. Louis to maintain ties with their German relatives over the decades of the later nineteenth century. Letters written from St. Louis (and evidently sent back to the family here at some point) relate details of domestic life in detail, and even include a hand-drawn map of the city and a sketch of the house on Chestnut Street. Items sent by Gustav’s sisters, Johanna Greiffenhagen and Theodora Bose, provide glimpses of developments in their respective households in Germany. The papers and photographs are unique among collections of the Becker Library with respect to these kinds of details.

Another remarkable talent of Baumgarten was as a freehand illustrator using ink or pencil on paper. Many small-format examples are to be found in the collection. The same skill with which he delineated organs of the body or microscopic views of cells was devoted to artistic sketches of people and outdoor scenes. Further examples of his work depicting prominent buildings of the city may be found in the print collections of the Missouri Historical Society.

Gustav Baumgarten led a full and active professional and social life into his mid-seventies. Aminda died in 1900 and he was cared for thereafter by their daughter, Alma (the family moved to a residence in the Central West End of St. Louis, 4900 Berlin Avenue – it was renamed Pershing Avenue after World War I). He was succeeded in practice by his son Walter. Baumgarten survived many of his close friends and colleagues with whom he had directed the fortunes of the St. Louis Medical College and local medical organizations. Baumgarten died in 1910, after what the obituaries refer to as a protracted illness. He was memorialized by a colleague, the ophthalmologist John Green as exemplifying the “distinguishing attributes of the wise physician, the helpful consultant, and the impressive teacher.”

Related Resources:

Back to Biographies