21st General Hospital During World War II – 1939-1945

The Spa, the Fairgrounds, and the Psychiatric Hospital

By Paul G. Anderson, PhD.

|

January 10, 1982 marked the fortieth anniversary of the activation of the 21st General Hospital, the World War II medical unit affiliated with Washington University and Barnes Hospital. Last September veterans of the unit gathered in St. Louis for a reunion. Three days of parties, banquets and meetings ensued, providing a fine opportunity to renew old friendships and to retell old war stories. The lasting esprit de corps of the 21st veterans reflects the fact that theirs was an effective unit and, in retrospect, a lucky one as well. Between 1943 and 1945 it made an impressive contribution to the Allied war effort in North Africa and Europe. During this period it operated from some rather unusual locations, including an Algerian spa, an Italian fairgrounds, and a French psychiatric hospital. By war’s end, 2,200 people had served with the unit which had treated 65,000 patients. The 21st was one of the largest troop hospitals and the most decorated medical unit in World War II.

The 21st was the successor to a World War I medical unit, Base Hospital 21, the first American military hospital to serve in France. Members were drawn from the staffs of Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes Hospital in 1917. The unit was stationed near Rouen, in northern France. After returning to the United States in 1919, Base Hospital 21 was designated a Reserve Officer Corps unit of the General Hospital category.

In 1939, when war broke out again in Europe, the executive officer of the reserve unit was Lee D. Cady, M.D., a 1922 graduate of Washington University School of Medicine and member of the clinical faculty in medicine. On his own initiative, he visited the War Department in Washington, D.C. to inquire whether the 21st would be called up were the United States to enter the war. This was no certainty at the time: a majority of Americans, indeed, opposed involvement in the new overseas conflict.

During the subsequent two years, however, the situation changed radically. The War Department drew up mobilization plans which included Reserve Army general hospitals. By late 1941, the United States had become deeply, if still unofficially, involved in supporting Great Britain against Germany. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 led quickly to official declarations of war against all the Axis powers. By the end of December, mobilization orders were sent to reserve unit officers throughout the country.

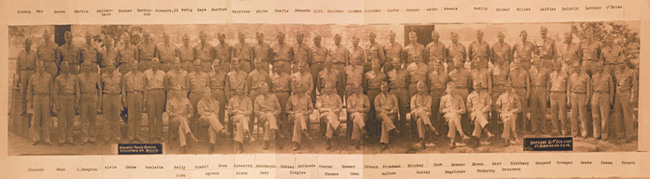

Dr. Cady, now lieutenant colonel, received the word on December 24. On January 10, 1942, he and an advance party of other medical officers from St. Louis traveled to Ft. Benning, Georgia. Two days later, the unit was activated as the 21st General Hospital. The ranks were increased by officers and enlisted men already in training at Ft. Benning. On February 1, they were joined by fifty-five nurses from Barnes Hospital nd the Washington University School of Nursing led by Lt. Lucille S. Spalding. Col. Robert E. Thomas, a Regular Army medical officer, was named as unit commander on February 15.

Several months of training followed. There was reason to believe that the 21st would be sent to serve in the South Pacific. But before any marching orders were received, important changes were made. Several cadres of officers and enlisted men were transferred from the 21st to start new training units. One such directive sent twenty officers to Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, where they formed the 21st Station Hospital. This unit, which included several Washington University physicians, eventually served in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Iran. Before the 21st General Hospital departed from Ft. Benning, Col. Thomas was replaced as commander by Col. Charles F. Davis. Finally, orders were received indicating that the hospital would be sent to the European theater, rather than to the Pacific.

The 21st left Ft. Benning October 13, 1942, bound for a staging area at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, near New York City. On October 20, the unit embarked from New York harbor aboard the S.S. Mariposa. The ship carried mainly combat troops, but, besides the 21st, there were also five other medical units on board. During most of the crossing, no convoy protection was afforded the Mariposa, despite imminent danger of attack by German submarines. Following a zigzag course through the ough waters of the North Atlantic, the vessel managed to reach its destination, Liverpool, England, in safety. But ther ships, including some loaded with medical supplies, were sunk by the enemy.

From Liverpool, the 21st was sent by train and truck to a billet in a suburb of Birmingham, Pheasey Farms Estate. The stay in England provided an inauspicious beginning to overseas duty. When the unit arrived in Birmingham, the city was so wrapped in fog that even the British Army guides lost direction. The weather remained poor. Rations were scarce. Perhaps most discouraging, it was learned that supplies intended for the 21st known to have reached Liverpool were distributed to other medical units.

While the unit was in England, plans were announced that the hospital would be a part of “Operation Torch,” an Allied offensive to establish control of North Africa. The 21st was transported back to Liverpool. There, with many other units, the personnel boarded the S.S. Monarch of Bermuda. It was more than a little discomforting to find that the vessel had suffered torpedo damage ten days earlier. Nevertheless, declared to be still seaworthy, the Monarch sailed on November 27 as part of the “Operation Torch” convoy.

The convoy rounded Ireland and ventured again through waters prowled by German submarines. Safely passing along the coasts of Spain and Portugal, the ships took brief refuge at Gibraltar. From there, they crossed unscathed to Algeria and landed at the Port of Mers-el-Kebir, near Oran, on December 6. Algeria had newly come under Free French control and thus its strategic resources were at Allied disposal. But the war was not far removed, for the German Afrika Korps, under Rommel, still held neighboring Tunisia.

The 21st bivouacked at Oran. An American evacuation hospital already on the spot assisted the new arrivals. But there were more frustrations in store. The normally sunny Algerian coast was that week pelted by heavy rains. The downpour turned the field where the hospital personnel camped into acres of mud. One veteran military man summed up his experience in verse:

I’ve seen mud on U.S. racetracks

That stopped horses near the wire.

I’ve seen mud on Flanders poppies

That stopped soldiers under fire.

I’ve seen mud in some U.S. camps

That would flatten beast or man.

But I’ve never seen the brand of mud

That's formed in old Oran.

Flash flooding one night hit the terrain where the nurses’ tents were pitched. The nurses reported seeing clothing and gear swept away in the swift, sudden rush of water.

The picture brightened at last late in December, when the 21st was transported into the interior of Algeria. The hospital was assigned to establish operations at a hot water spa. The place, called Bou Hanifia, was located at an oasis in he rocky desert plateau sixty miles south of Oran. The largest building in Bou Hanifia was the Grand Hotel, which rose out of the desert like an art deco mirage. It was chosen to house the main medical and surgical functions. Several smaller hotels in town were also taken over for hospital uses. The hot spring water pumped into the baths of these establishments was particularly welcome.

Inevitably, there was friction at first between the American newcomers and the French civilian population. There were also difficulties and uncertainties in dealing with the native Algerians. One touchy problem, from the American point of view, was an immediate need to raise the level of sanitation at most spa facilities. For weeks, members of the 21st scrubbed and scoured buildings and laid down new plumbing and sewage lines. In the process, hospital cadre learned that they had to be diplomats as well as healers. They gradually won the trust and cooperation of local leaders. It helped immensely, of course, that the 21st brought “business” to the war-isolated resort and, thereby, revenue and employment to the residents of the spa village.

A solitary first patient was admitted December 24. Hospital functions began in earnest on January 2, 1943, when 472 beds were ready. The supply shortage was now critical. Makeshift instruments were used in the first days of surgical operations. Medicines and bandages were administered very sparingly. The problem was gradually alleviated as more and more Allied convoys reached the Mediterranean Base Section. But 21st officers were at times so impatient as to risk court martial by making unauthorized “scrounging” expeditions to the depots at Oran.

Col. Davis was unexpectedly transferred to another unit in late January. Left to assume temporary command was Lt. Col. Cady. Weeks went by without a replacement for Davis named. Ultimately, with the help of friends higher up, Cady was promoted to colonel and given permanent command of the hospital. Cady revealed a considerable talent for public relations. For one thing, he knew how to exploit Bou Hanifia’s resort facilities fully. Hotel kitchens were encouraged to do their utmost to embellish the dull Army chow. Ranking visitors, even those needing no medical or dental treatments, were welcomed to the spa. As souvenirs, they were given certificates naming them “Honorary Arabs of Bou Hanifia.” The hotel roof gardens were opened up. Dances were held. Nurses were permitted to send home for their party dresses. Festivals were arranged to which the native population of the spa village was invited.

All the efforts to boost morale and to cement good relations paid off in terms of hospital efficiency. Bed capacity steadily increased. When all appropriate spaces in the hotels were full, temporary buildings were erected to house additional wards. A rehabilitation section was established for special treatment of the wounded.

Battles in Tunisia in the spring of 1943 led to capture of thousands of German and Italian troops. Up to 200 of the enemy wounded were treated by the 21st at one time. Handling of prisoners of war necessarily increased the complexity of military operations at Bou Hanifia. Among the units called to help were an Army Engineer Regiment, several military police platoons, a company of Algerian guards, and four Italian POW companies.

At its largest while in Algeria, the 21st had over 4,000 beds. (In comparison, in 1980 Washington University Medical Center had 1,901 beds.) The 21st staff was pressed to handle casualties from the American and British forces which invaded Sicily in July. The number of patients gradually began to decrease once the Allies conquered all of Sicily and launched attacks on the Italian mainland. In November, the order came to “cease construction” at Bou Hanifia and restore facilities of the spa to their prewar functions. In a year of service in the North African campaign, the hospital treated 20,989 patients. Some of these cases involved important surgical innovations, such as the first decortication of a lung in wartime, performed by Maj. Thomas H. Burford. The Neurosurgical Service under Maj. Henry G. Schwartz had developed techniques in emplacement of acrylic skull plates and nerve suture. New methods were also devised in orthopedics and plastic surgery. Toward the end of operations at Bou Hanifia, a thousand-bed Venereal Disease Section had been established. The Dental Service attached to the 21st had performed 21,299 treatments.

With hospital equipment packed into more than three thousand crates, the unit gathered again at Oran. The destination this time was Naples, Italy. The nurses sailed December 4 on the hospital ship Shamrock. The remainder of the unit boarded the British transport vessel HMS Cameronia two days later. Col. Cady found himself to be the ranking American officer on board and thus in charge of all U.S. personnel during the voyage. They numbered four thousand, including officers, enlisted men, W.A.C.’s and Italian POW’s. The Southern Italian coasts were still within range of German bombers and were frequently under their attack. Once again, luck was with the 21st and the Cameronia arrived at Naples unharmed. Cady acquitted himself well as a troop commander.

Shortly before the war began, the Mussolini regime had opened a fairgrounds outside of Naples. Its theme was the promotion of Italian colonies. The facilities included exhibit halls for each of the subjugated territories. After the Allies took control of Naples, the fairgrounds was designated a medical center, to be run by several units, including the 21st. Near the fairgrounds was another tourist attraction, Terme di Agnano, like Bou Hanifia a hot water spa. There, where Italy’s wealthy once took the cure, the officers of the 21st were billeted.

After the relative comforts of Bou Hanifia, Naples inflicted substantial hardships on the unit. Fierce fighting continued only a short distance away. Cold rains drenched the region throughout December and January. Many fairgrounds buildings were badly bomb damaged. Tents were used to shelter many of the sick and wounded while repairs were being made. During these difficult days, members of the unit were themselves hospitalized with upper respiratory infections and fatigue. But, despite all these problems, the hospital was able to regain operating efficiency within days of arrival at the fairgrounds.

The surgical service was set up in the “Albania” building, its roof patched with plexiglass and gobs of asphalt. A heroic mural of Mussolini, peppered now with bullet holes, looked down on operations. A recovery ward was established in a chamber where decoration ironically lauded the prowess of the Italian soldier. Tents were erected in a courtyard to shelter the officers’ mess. Nearby was the “Libya” building, housing hospital headquarters. The fairgrounds had included a small zoo. A barn erected for giraffes was allotted to the enlisted men’s club, and the small animal house was converted into a bakery.

In January 1944, Allied forces invaded the central Italian coastline at Anzio. In the weeks that followed, attacks were launched on German positions in the mountains, notably at Cassino. Trainloads and shiploads of casualties from these engagements, as many as three hundred at a time, were brought to the hospital, straining staff and bed capacity to the utmost. In addition, the unit was called upon to help stem a typhus epidemic in Naples. The most critical period of service to the Italian campaign came in June, with battles leading to the fall of Rome. Bed capacity of the 21st at that time reached three thousand.

The success of the D-Day invasion of Normandy (June 6, 1944) permitted Allied offensives in southern France in August. By September, territory as far north as Lorraine had been liberated from German control. Orders were sent for the 21st to follow and establish operations anew on French soil. On September 25, the unit pulled out of the Naples facility. Just short of 15,000 new patient records had been added to hospital statistics. The 21st was recognized as one of the finest medical units in the European theater, and not only by Americans. For assistance to the Free French forces, Gen. Alphonse Juin awarded the 21st a French unit citation.

By this time, hospital personnel were masters of the complicated art of relocation. Col. Cady received authorization for a 4,000 bed hospital. Whole wards and all necessary equipment were capsuled to withstand transport by ship, rail, and truck to a destination yet undetermined. Four ships carried personnel and cargo from Naples. Early in October the convoy reached Marseilles safely. Once in port, the 21st command maintained the utmost vigilance to keep their precious cargo intact. Col. Cady and two other officers, Lt. Cols. Sim F. Beam and John F. Patton, flew north to the U.S. Seventh Army in Lorraine. There it was determined that the new location for the 21st would be a psychiatric hospital near Mirecourt, south of Nancy.

Red tape delayed efforts to move the hospital out of Marseilles for several days. Finally, orders came through giving the 21st equal priority with ammunition bound for the front lines. A hospital train for personnel and three freight trains were required to carry the unit northward. On arrival in Mirecourt, several convoys of trucks met the trains to take the 21st to Ravenel Hospital.

Once again, the unit found itself uncomfortably close to a battle zone. On October 21, less than a month after the 21st had left Naples, it was accepting patients anew. The psychiatric hospital buildings had been in the final stages of construction when the war began. They were not damaged during the German occupation. Now, with finishing touches by American engineers, the facility was admirably suited to the needs of the 21st. It boasted spacious wards and central heat. By November, over three thousand patients were being treated daily.

The fighting grew intense as the lines edged closer to the German border. As increasing numbers of casualties were brought to the hospital, it was sometimes necessary to treat POW’s alongside Allied servicemen. Understandably, the staff was concerned about possible outbreaks of violence in the wards. This situation was alleviated to a degree early in December, when part of the staff of a German hospital was captured at Strasbourg and sent to Ravenel. These physicians and nurses were put to work caring for their own.

The 21st endured perhaps its hardest test in late December, during the “Battle of the Bulge.” The surprise German counteroffensive breached Allied lines in Belgium and Luxembourg and, for ten critical days, threatened a new invasion of France. Plans to evacuate the hospital were hastily drawn up. On December 26, the buildings at Ravenel were strafed by enemy planes; one bomb hit the grounds, causing slight damage.

That very day, it turned out, the German drive was stopped. The hospital, of course, accepted a great many of the wounded from the battle. The pressure continued as the struggle crossed the border into Germany itself. In January 1945, the 21st expanded to 4,040 beds. On January 7, the hospital treated its 50,000th patient. The facilities at Ravenel were used to their fullest extent. Sick and wounded were cared for even in the attics of buildings. Ambulatory patients were pressed into service on the wards and in the hospital headquarters.

February 1945 brought a marked measure of relief to the exhausted staff of the 21st. With front lines now east of the Rhine River and German resistance to Allied assaults collapsing, fewer wounded were brought daily to the hospital. The patient census dropped below two thousand that month.

With the end of the war in sight, the multinational character of Allied forces on the Western Front, as viewed from the 21st, became apparent. Besides Americans, patients included Britons, Canadians, Poles, Yugoslavs, Italians and Germans in sizable numbers. Four Italian sanitary companies served on the grounds of Ravenel. There were enough talented musicians among the German POW ranks to form a fifty-five piece symphony orchestra. The orchestra enlivened special ceremonies at the hospital and, in smaller ensembles, played in the wards and mess halls.

The long-awaited end of the war in Europe, V-E Day, came May 8. Victory brought a new variety of challenges to the hospital command. The number of patients dwindled, but many severely wounded remained for treatment. Meanwhile, the medical and nursing officers were needed for other assignments and were rapidly transferred out of the unit, creating staffing shortages. Col. Cady and his remaining cadre struggled to maintain hospital services despite daily changes in the duty roster.

On September 20, the U.S. Army bestowed its meritorious Service Unit Plaque on the 21st. The citation read, in part: “The professional skill and tireless devotion to duty demonstrated by the personnel of the 21st General Hospital were in keeping with the highest traditions of the Armed Forces of the United States.” The award, it is true, came too late to be distributed personally to most hospital personnel. The remaining staff at Ravenel by this date had been relieved of medical duties and were packing for the voyage home.

Final statistics compiled by the Unit were impressive. They indicate that the 21st admitted 65,503 patients in its nearly three years of overseas service. The total surgical operations numbered 33,440. Dental treatments amounted to 69,375. The hospital laboratories had run 246,805 tests. Blood transfusions given were 11,258. The Convalescent and Rehabilitation Section treated 21,175 patients. In three years, over 2,200 persons had served as members of the 21st.

After a short period at a staging area near Marseilles, Col. Cady and his staff boarded the victory ship Westminster, which sailed October 28. The ship landed at Boston November 7. The members of the 21st were taken to Camp Myles Standish, given an official welcome, and reoriented for their imminent return to civilian life.

The 21st ceased to exist as an active military unit at this point. (It has since been revived as a U.S. Army Reserve General Hospital.) Yet the careers of those who had served with the hospital during the war continued to be influenced profoundly by the experience. Dr. Cady became a director of Veterans Administration hospitals in Dallas and Houston. Many of the other medical and nursing officers returned to St. Louis, a substantial number to resume practice at the Washington University Medical Center.

Scores of general hospital, evacuation hospitals, station hospitals, and other medical units served the Allied cause well in World War II. The record of the 21st General Hospital was among the best and is one of which Washington University School of Medicine can justifiably be proud.

This article originally appeared in the Washington University School of Medicine’s Outlook Magazine, Vol. XIX, No.1 (Spring 1982).

Back to Top